Call for child payment increase as prices spiral

- Published

The charities said childcare costs were preventing many parents getting back into work

A benefit payment for children in Scotland should be increased again next year to help struggling families cope with the cost of living crisis, charities have said.

Families eligible for the Scottish Child Payment, external receive £20 a week for every child under the age of six.

The payments will be increased to £25 a week for every child under 16 when the scheme is expanded later this year.

Child poverty campaigners say this still does not go far enough.

A report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Save the Children said the Scottish government was still likely to narrowly miss its interim child poverty targets, external despite the expansion of the payments.

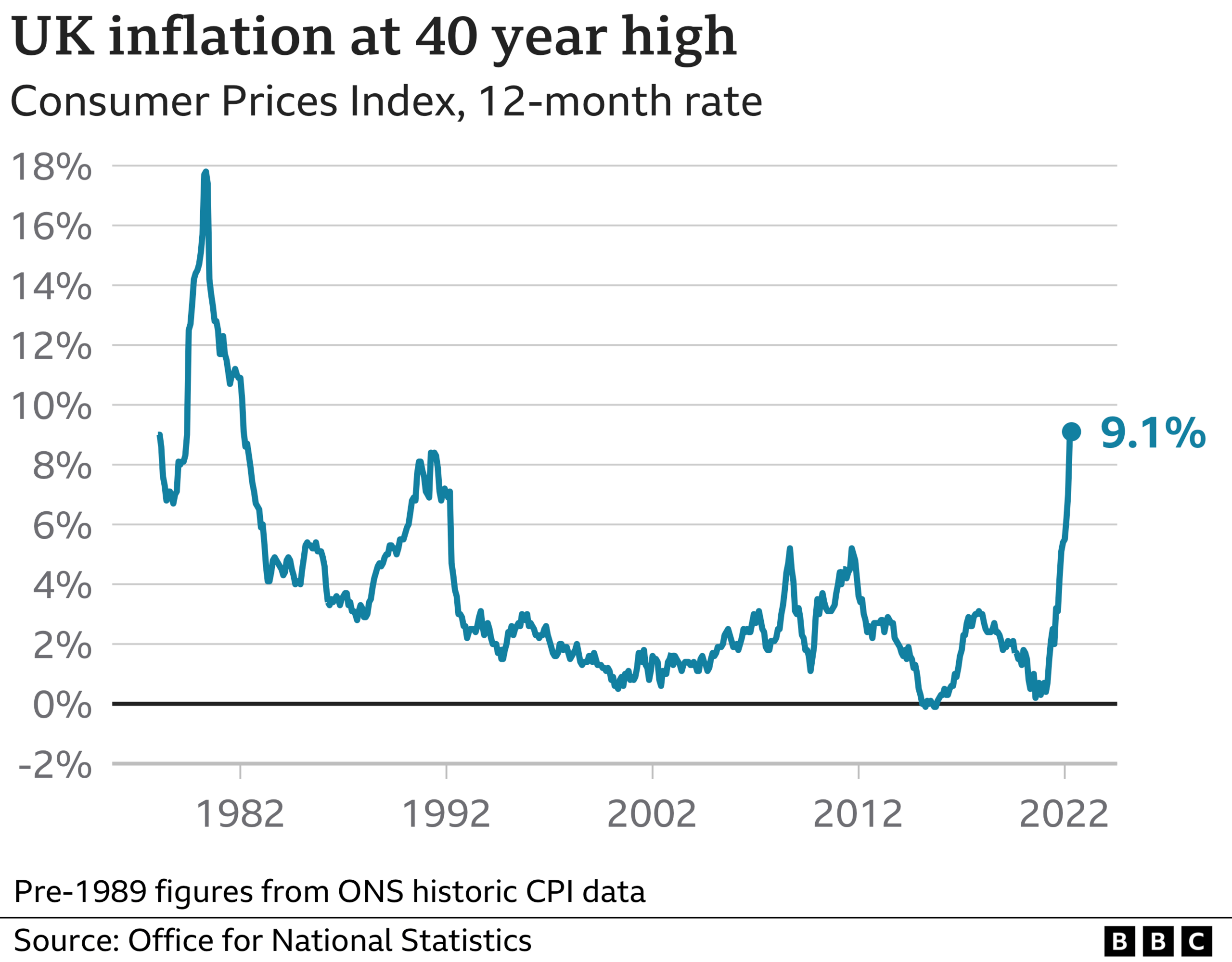

It was published on the day inflation in the UK hit 9.1% - meaning prices for essential items such as food, energy and fuel are increasing at their fastest rate for 40 years.

The charities said people across the UK were facing one of the most severe attacks on their standard of living in decades, and called for child poverty to be treated with the same urgency as the Covid pandemic was.

Their report added: "We have known for a long time that parents are often making sacrifices to ensure that their children do not go without food and clothes and warmth.

"This crisis is such that it is almost impossible for parents to shelter their children from this storm."

The two charities said many of the financial issues faced by families predated both Covid and the inflation crisis.

They praised the Scottish government for introducing the Scottish Child Payment - which is paid in addition to the UK-wide Child Benefit - and described it as a "crucial lifeline to many with young children".

But they said the government should commit to increasing the payment above the rate of inflation next year, and to £40 a week for every child by the next Scottish Parliament election in 2026.

Without this increase, they said the government was unlikely to achieve its goal of reducing the number of children living in relative poverty to 18% by 2023/24 and to less than 10% by 2030.

Higher food prices, particularly for bread, cereal and meat, have driven the latest rise in the cost of living

They also called for the scheme to be rolled out to children over the age of six as quickly as possible to ensure struggling families do not lose the weekly payment once their child has their sixth birthday.

Families are classed as being in relative poverty if they have a total income of less than £18,000 a year.

It was estimated that 24% of children in Scotland - about 240,000 - were living in relative poverty before the Covid pandemic.

The government predicted in March that it would meet its interim goal by cutting the figure to 17% next year - which it said would be the equivalent of 60,000 fewer children living in poverty than in 2017.

Analysis by economists from the Fraser of Allander Institute said this was optimistic - with their modelling suggesting the government is likely to narrowly miss the 18% target.

The government's four-year child poverty plan - called Best Start, Bright Futures - was unveiled earlier this year, with a focus on helping parents get into work.

But the charities said many parents were struggling to get employment that "paid enough to get by".

They called on the government to "refocus efforts from bringing parents closer to the labour market, to bringing the labour market closer to parents".

The report added: "We heard the role that the inflexibility, inaccessibility and cost of childcare has in locking parents away from job opportunities.

"We heard how services designed, in theory, to support people are often a faceless "system" that increases the anxiety that people live under, rather than helping them to manage it."

'Toxic brew'

It said this was having a huge impact on people's mental health, with people facing the constant worry of paying bills, putting food on the table or a phone call from the Job Centre.

Matched with the scarcity of services to both avoid and treat mental ill-health, this stress had created a "toxic brew that is already holding people back".

The success of the government's child poverty plan should therefore not just be measured on whether targets are met, they argued, but on making these "unacceptable" conditions a thing of the past.

Chris Birt, associate director at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, said: "The Scottish government's Plan to reduce child poverty will do just that but our discussions with parents and our analysis shows that it doesn't go far enough.

"Families in Scotland face a toxic mix of high inflation, low and insecure incomes (from work and social security) and poor mental wellbeing.

"They need the Scottish government to take action now - they have got the diagnosis right, but the prescription needs to be much stronger."

What has the reaction been?

Scottish Finance Secretary Kate Forbes said she wanted to ensure the Scottish Child Payment "goes as far as possible", but stressed that it was one of a series of schemes that are aimed at helping families.

She added: "My budget is a fixed budget, so anything that we do uniquely in Scotland - like the Scottish Child Payment - comes from our own budget.

"We are already on track to spend £1.3bn more on benefit expenditure in Scotland than the funding we will receive from the UK government.

"I hope sincerely that our own budget will rise in line with inflation and we are able to continue to protect all of these schemes in line with inflation".

Scottish Labour MSP Pam Duncan-Glancy said the report showed that the government was relying one measure and was not delivering the "bolder action that is needed to address the shameful levels of child poverty in Scotland".

She said: "It is clear that we need to make better use of the levers the Scottish government has if we are to meet our legal and moral duty to drive down poverty and give every child a fair start in life."