Global pandemic fears on islands hit by bird flu

- Published

Guillemots on the Isle of May national nature reserve

David Steel is usually sad to see the seabirds heading south from the Isle of May, but this year he is glad that at least some are escaping their crowded nesting sites which have become a breeding ground for the new lethal variant of avian flu.

The manager of the nature reserve in the Firth of Forth tells me his big worry now is that they might take the disease with them.

A global pandemic, which could return to devastate the colony again next spring, is a big concern, Mr Steel says. This year has been terrible enough.

Over the course of spring and summer, a new and deadly variant of bird flu has been spreading through seabird colonies around Scotland.

From Shetland to the Farne Islands in Northumbria, washed-up bodies of dead birds are becoming a more common sight.

Scottish government agency NatureScot recently closed 23 islands to try to manage the outbreak.

David Steel is concerned avian flu will become a global pandemic

The Isle of May, a home during the spring and summer for thousands of seabirds, was one of them.

I was given special permission to visit the island, which sits in the outer Firth of Forth, about five miles (8km) off the Fife coast.

As our boat approached, grey seals bobbed out of the water, shags were perched on the rocks around the small harbour and puffins struck out into the steely waters.

Arctic terns wheeled overhead, their warning cries telling us that we were too close to their chicks, hidden among the rocks and sea campion.

Soon they will start epic journeys to Antarctica.

"The winter is crucial," Mr Steel says.

"We've got to start to learn more about this and also make decisions about next season, because obviously there's a big risk that our birds, these Arctic terns beside me here, they're going to take it south with them.

"Will they take it into other colonies? Will they take it into albatross colonies in the south, penguin colonies, so it becomes a global pandemic then and comes back next spring?

"That is the worry, it really is, it's a big concern".

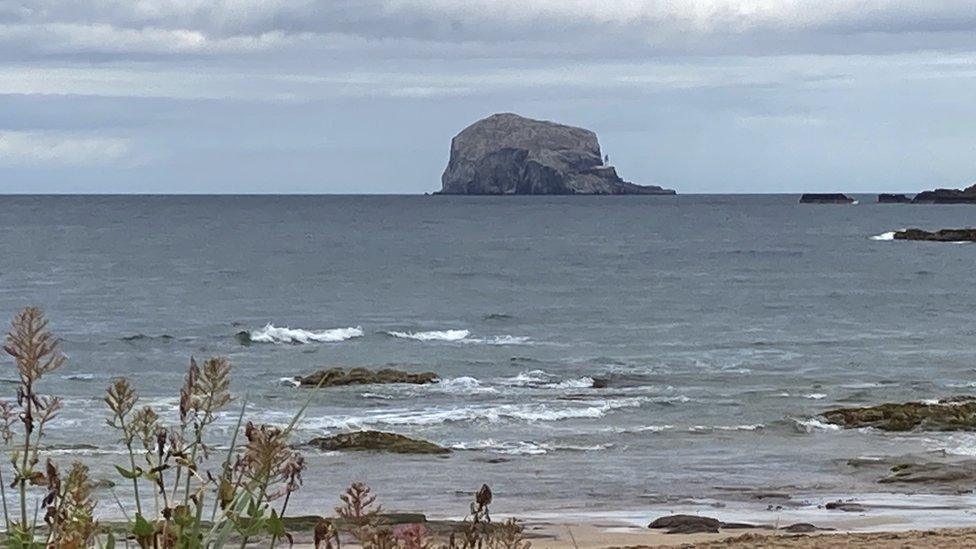

Gannets at Bass Rock have been badly hit by the avian flu

On the path from the harbour, we find the body of a puffling, a young puffin, which didn't even make it into the water.

Mr Steel says it has been devastating to watch so many birds die and to know that there is almost nothing he can do about it.

Dramatic changes

On the other side of the Firth, at the Scottish Seabird Centre in East Lothian, those concerns are echoed by its chief executive, Susan Davies.

Over the past few months, she has seen dramatic changes on the Bass Rock, which is just off the shore of North Berwick.

Normally, huge areas of it are covered by gannets. But this year, gaps have appeared and grown ever larger. The lower slopes have become littered with dead birds.

The Bass Rock colony lies off the coast of North Berwick

Ms Davies says the UK government's Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and NatureScot are working together on the crisis.

She says: "One of the primary reasons behind that is to bring some coordination, to put a better surveillance plan in at key sites, to now understand the way in which the disease is changing and how it might mutate and affect other species."

Could those other species include humans?

Ms Davies says, "Some of the research that has been funded by Defra this year is also looking at what mutations would now have to take place in this form of highly pathogenic avian flu for it to be transmissible to people and what control measures would they put in place if those mutations happened."

That is an alarming prospect and one which is brought into sharp focus by the devastating impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

That crisis may have loosened its grip, but it has not gone away.

And the implications of avian flu for birds and other species on the planet remain deeply troubling and unknown.

- Published20 July 2022