Where does Scotland stand with the attainment gap?

- Published

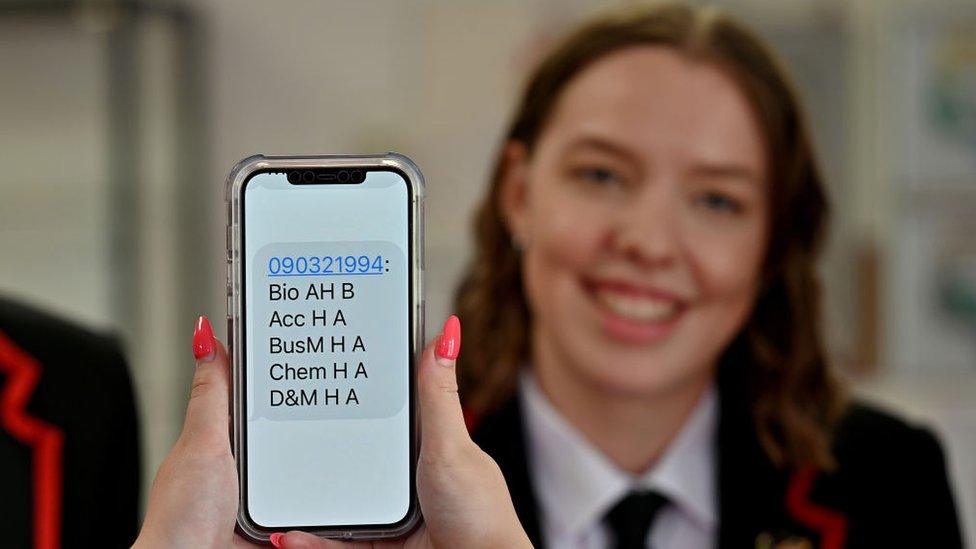

As pupils across Scotland receive their results, the BBC has looked at where the country's attainment gap stands - and how it has been affected by exams, the pandemic and government policy.

What is the attainment gap?

In a nutshell, children from richer families tend to do better at school than children from poorer families.

For the disadvantaged pupil — and in turn for their children — this means a lower chance of progressing to further education and a decent job.

The complex and difficult task of breaking this cycle of poverty has been a stated "priority" of Nicola Sturgeon since she took charge of the Scottish government eight years ago.

In 2015 the first minister told the Scottish National Party conference she wanted to be judged on closing the attainment gap.

"I've put my own neck on the line," she said.

The SNP's 2016 programme for government, external pledged to "substantially eliminate [the attainment gap] within a decade". Education was the "defining mission" of Ms Sturgeon's government, the party said.

How is that going?

Badly.

In March 2021 the public spending watchdog Audit Scotland reported that "the poverty-related attainment gap remains wide and inequalities have been exacerbated by Covid-19."

The report acknowledged that some progress had been made but concluded it was "limited and falls short of the Scottish government's aims."

At Holyrood on 18 May Education Secretary Shirley-Anne Somerville appeared to concede, external that the SNP would not meet its pledge to "substantially eliminate" the attainment gap by 2026, telling MSPs "I will not set an arbitrary date for when the attainment gap will be closed, particularly so close to the experiences that we are still having with the pandemic."

Today, though, Ms Somerville told me that while Covid had made the task more difficult, the government remained "absolutely determined" to fulfil the promise of substantially eliminating the gap by 2026, insisting "we're putting the investment in" to make it happen.

Is the pandemic to blame?

It certainly hasn't helped.

Areas of high deprivation were "hit hardest by Covid," said Leanne McGuire, who chairs Glasgow City Parents Group, which argues for more educational resources for poorer families.

Leanne McGuire, who chairs the Glasgow City Parents Group

Less well-off parents couldn't afford to purchase devices for home schooling and often were not able to take time off work to help educate their children, explained Ms McGuire.

"If you've got the money to hire a private tutor or if you've got the money to pay for private therapy for your child, obviously that child's going to excel further," she added.

Her conclusions are supported by last year's Audit Scotland report, external which warned that "variation in the learning experience of children and young people" during the pandemic could well "exacerbate the poverty-related attainment gap."

What about longer-term trends?

We are around a decade in to a controversial revamp of Scottish education called the Curriculum for Excellence, an "outcome-based curriculum" with little prescribed content, intended to help young people "gain the knowledge, skills and attributes needed for life in the 21st century".

Students (from left) Michael Stewart, Aaron Boyack, John Poole and Claire McNab at Auchmuty High School in Glenrothes

The project, instigated by a Labour/Liberal Democrat coalition and continued by the SNP, has been praised by some, including the OECD.

The latter described it as offering an "inspiring and widely supported philosophy of education", external but critics say it has been a disaster which has made closing the attainment gap harder.

Lindsay Paterson, professor of educational policy at the University of Edinburgh, argues that education should focus first and foremost on instilling knowledge rather than on developing "soft skills" such as the ability to work in teams.

"Unless schools aim to devote themselves to improving young people's intellectual capacities, for most children there will be no other opportunities for that to happen," he said, adding that this particularly applied to pupils "who don't have the good fortune of having parents who themselves are well-educated to stimulate that kind of development at home."

Are exams part of the problem?

In 2020 and 2021 formal exams were shelved as the government prioritised preventing the spread of disease.

Instead, a system of teacher assessments and, later, hastily arranged tests was used, provoking controversy for the way in which many disadvantaged pupils were initially marked down by moderators.

After the grades had been reassessed in 2020 the attainment gap appeared to have narrowed but in 2021 it widened again.

Holyrood's education committee has since taken evidence from about 60 young people and reported that while they had found the rapid shift to classroom assessments stressful, on the whole they nonetheless wanted to move away from "high pressure and high stakes", external end-of-year exams in which final grade awards were determined by "on-the-day performance rather than recognising effort throughout the year."

Many of the students instead favoured "a system of continuous assessment, including practical work and presentations as well as written tests."

The Scottish government has said that it expects to continue with externally assessed exams but Prof Louise Hayward of the University of Glasgow - who is chairing a review of qualifications and exams for the Scottish government - insists nothing is off the table, external.

In our interview, Ms Somerville denied that her comments had prejudiced the inquiry from the outset, saying there were "different ways that you can assess people and the balance can be perhaps different".

What is the Scottish government doing to close the attainment gap?

It is spending a lot of taxpayers' money — almost £1bn since 2015.

Some of that money was allocated to head teachers throughout Scotland to spend as they saw fit, such as employing extra staff, buying equipment or funding trips.

Education Secretary Shirley-Anne Somerville announced attainment gap funding would be shared by local authorities

Another chunk of cash was directed at nine local authority areas with high levels of deprivation: Clackmannanshire, Dundee, East Ayrshire, Glasgow, Inverclyde, North Ayrshire, North Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire and West Dunbartonshire.

Last year Ms Somerville announced that those targeted funds would in future be shared by all 32 Scottish councils, a change which prompted Labour to decry "callous cuts" in the poorest communities and the Conservatives to accuse the SNP of "rehashing the same failing initiatives".

Ms Somerville has also, on the recommendation of the OECD report, ordered the scrapping and replacement of Scotland's education and exams agencies, Education Scotland and the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA).

What do critics want?

More information for one thing.

A report, external for think tank Reform Scotland criticised a decision to abandon the Scottish Survey of Literacy and Numeracy in 2017 - this assessed performance in P4, P7 and S2.

The report also lamented Scotland's withdrawal from international surveys assessing performance in science, maths and literacy.

"We know less now about the performance of Scotland's schools than at any time since the 1950s" concluded the report, a situation Prof Paterson describes as scandalous.

"Scotland is now worse served than any other country in Europe, as far as I can see, and it's certainly far worse served than England," he argued.

What else might work?

For Leanne McGuire, of Glasgow City Parents Group, access to state-funded tutoring for all pupils regardless of their means would be transformative.

"I can't see how they're going to be able to close the attainment gap without putting something like that in place," she said.

Other ideas such as improving school leadership and recruiting and training more high quality teachers are fleshed out here, external.

Whatever the methods, the education secretary has now reiterated that closing the gap remains a defining mission by which the Scottish government should be judged. The clock is ticking.

- Published9 August 2022

- Published9 August 2022

- Published23 March 2021

- Published23 November 2021