The patients locked in secure hospitals for decades

- Published

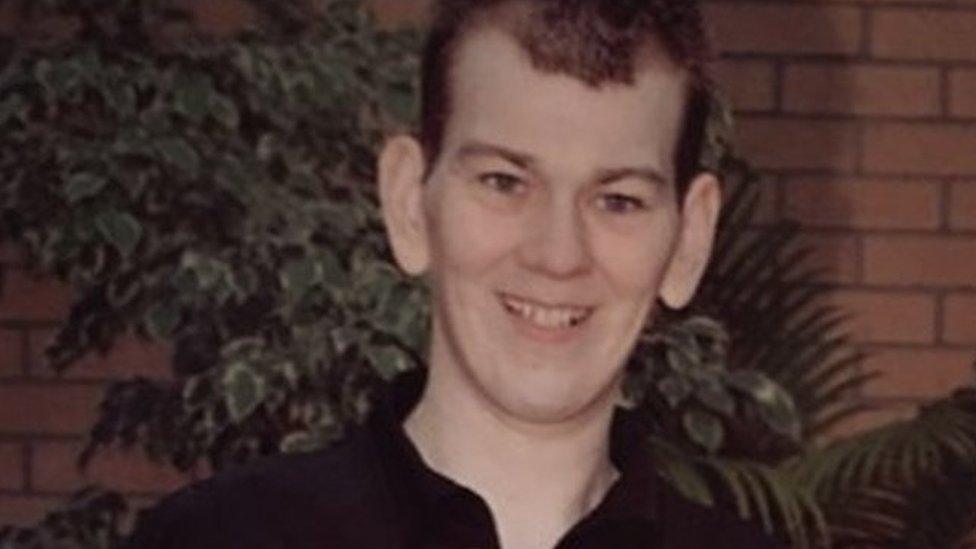

The family of Fraser Malcolm (left) fear he will not be released from hospital

Scots with learning disabilities and autism have been locked in secure hospitals and psychiatric wards for decades, a BBC investigation has found.

They remain unable to get out despite Scottish ministers saying 22 years ago that they should be living independently in the community.

BBC Disclosure found one person with a learning disability who had been behind locked doors in hospital for 25 years.

Another was cleared for release eight years ago but is still in hospital.

Some families said their relatives had been left to rot.

The Scottish government said the findings were unacceptable and that local services must do more to get people into their own homes.

Freedom of Information requests, made as part of the BBC Disclosure documentary, revealed that 15 Scots with learning disabilities and autism had been living for more than 20 years in hospital.

It also found at least 40 people in hospital for more than 10 years and 129 in hospital for more than a year.

In addition, nine people with autism and learning disabilities are currently in Carstairs, a high security state psychiatric hospital in South Lanarkshire, which houses some of Scotland's most serious criminal offenders.

None of these patients with learning disabilities were convicted of a crime before they were sent there.

Stuck in Carstairs for 13 years

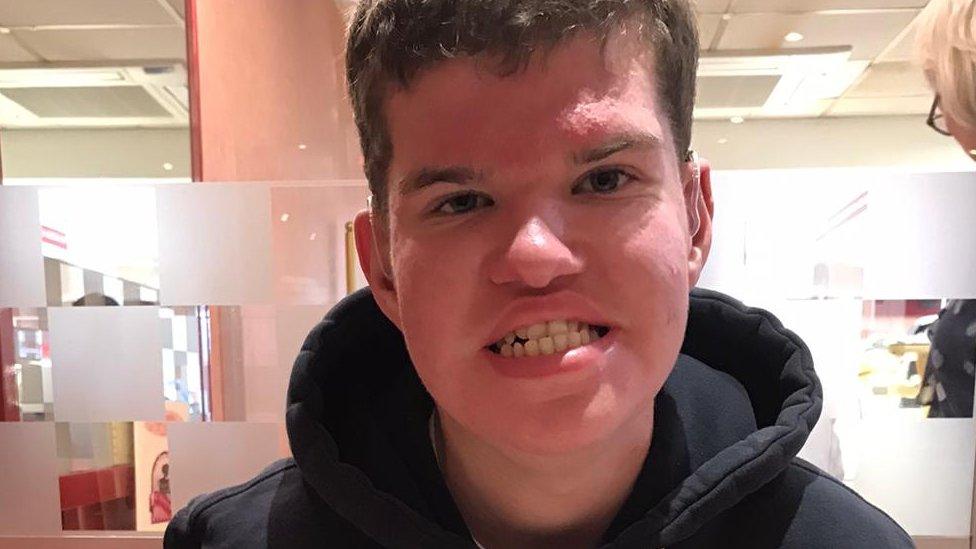

Kyle Gibbon, who has learning disabilities and autism, has been in a high security psychiatric hospital for 13 years

Kyle Gibbon, who is now 34, has been in Carstairs for 13 years.

Before that Kyle, who has learning disabilities and autism, was an inpatient in a hospital in Aberdeen but was attending college and regularly went bowling or to the cinema.

He was allowed home at weekends and was preparing to move into his own flat.

But all that changed on the day his mother Tracey went to pick him up from hospital to see the sofa that had just been delivered to his new home.

When Kyle was younger he rode horses

"When I arrived there I was told that he wasn't getting out," Tracey said.

The nurses did not know why and Tracey was put in a side room with Kyle.

She said her son did not know what was wrong and became very emotional and upset. He grabbed hold of her and asked her not to leave him.

"The next thing I know, it was about at least 10 staff piled into this room, took me down on the ground with Kyle, and injected him in front of me," Tracey said.

"I was absolutely horrified. I couldn't believe it."

Kyle was accused of trashing his room and assaulting a doctor.

Kyle was about to move into his own flat before he was admitted to Carstairs

The next time his mother saw him he was in Carstairs, the only maximum security hospital in Scotland, which holds those who have committed particularly violent crimes.

When Kyle was admitted in 2009 he had not been convicted of any crime.

Seven years later he received a compulsion order from a court for assaulting a nurse.

The order has special measures attached which mean he could now be held in Carstairs indefinitely.

Kyle has repeatedly asked to be let out but, since being in Carstairs, his mother said his behaviour had deteriorated and he is now considered too high risk.

The Carstairs website says its "principal aim is to rehabilitate patients, ensuring safe transfer to appropriate lower levels of security".

However, the BBC found there were nine patients there with a primary diagnosis of autism or a learning disability who have been locked in Carstairs for an average of eight and a half years.

Dr Jana de Villiers, consultant psychiatrist for The State Hospital's Intellectual Disability Service, told the BBC she can't discuss any particular cases but the average length of stay will include a wide range of people some of whom will be in for much shorter periods and some for longer.

She said the people they see often have multiple mental and physical health needs such as epilepsy or other conditions.

"What we do is focus on making sure we get the best outcomes and we have quite good success with that," Dr Villiers said.

"But as with any health condition there are people who we do everything we can to help them progress but the nature of their impairments means that they are much more long term and can be exceptionally difficult to change."

Dr Villiers said there were many avenues for patients and families to have independent scrutiny of the care and treatment being provided and to be able to challenge detentions.

She said they can ask for other independent psychiatric reviews.

"I would also say many families are very appreciative of the care being delivered at the State Hospital and would have concerns about any particular patient moving where they don't feel those needs would be met in the way they are at the State Hospital," Dr Villiers said.

She said she agreed that there was a lack of local community provision for people with learning disabilities but said that was a different issue from those who are held in Carstairs, who all need to be in maximum security.

Everyone can live in the community

Bethany was considered so high risk that she was locked in a seclusion cell in hospital aged 15

Jeremy's daughter Bethany was considered so high risk as a teenager that she was locked in a seclusion cell in hospital, aged 15, for almost three years.

Her situation only changed after her case was highlighted by BBC File on 4.

"They viewed Beth as being so dangerous they wouldn't open the door unless they had five members of staff," said Jeremy.

Beth is autistic. At the time doctors said she could not be released from seclusion because she was too much of a risk to herself and others.

Four years on, she is able to go out on dog walks and fishing trips. She is due to move into her own home within months.

Bethany's dad Jeremy says his daughter is an example of what can be achieved

Prof Andrew McDonnell, a clinical psychologist and professor of autism studies at Birmingham City University, said people with autism and learning disabilities can live safely in the community with the right level of support and expertise.

And they should only ever be admitted to hospital for a matter of months, he said.

He said forcing those with sensory issues to conform to a noisy psychiatric ward often made people's behaviour deteriorate.

Prof McDonnell said people were being incarcerated but it was not as a punishment for something they had done.

"This is just people who don't fit," he said.

"And these individuals who don't fit are often the individuals that scare staff the most."

Prof McDonnell said we should not only ever be using these environments on a temporary basis.

Waste of life

Thousands of people with learning disabilities were living in long stay hospitals prior to the 1990s when it was agreed it was inhumane.

The Scottish government published The Same As You? Report in 2000, which established the right for everyone with a learning disability to live in their own homes and communities.

It said: "People's homes should not be in hospitals".

But hundreds of people with learning disabilities and or autism are still living far from family, locked in psychiatric wards or other units.

The FoI shows NHS Lothian has a patient who has been in for more than 25 years.

NHS Forth Valley has a patient who has been in for 19 years and NHS Grampian has someone who has been in a secure unit for more than 18 years.

The longest delayed discharge - someone cleared for release - is in Lothian and is 8.9 years.

The three health boards said they could not comment on individual cases because of patient confidentiality.

They said they were working to provide the best possible care and that it can be challenging to find community places for those with the most complex needs.

Dr Anne Macdonald said it is not acceptable that people are living in hospital when there is no clinical reason for them to be there

Dr Anne MacDonald, the Scottish government adviser on learning disabilities, said people being in hospital for 10 or 15 years was a "waste" and it was "not a life".

She said that people might think that the best place for people with complex support needs was in hospital but that was not the case.

"It's absolutely not acceptable that people are living in hospital when there's no clinical reason for them to be there," she said.

"People with learning disabilities should not be living in hospital."

Dr MacDonald said it was a human rights issue to have a home and to be able to have a connection with your family.

"We shouldn't just be accepting it as status quo," she said.

"We need to be working harder on this, and doing better."

Dr MacDonald said she was shocked by the revelation that one patient has been held in hospital for 25 years.

"It's an awful statistic," she said.

"It's a waste of the opportunity to have a life."

Being sectioned

Fraser Malcolm's family was told he would be sent to hospital for a short time to help him stabilise

Fraser Malcolm has a rare genetic condition that has affected his development

He has a learning disability and he has limited speech. Two years ago, when Fraser was 17, he started being aggressive towards his family.

They asked social work and the police for help. They were told he would be sent to hospital for a short time to help him stabilise.

But Fraser was sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

This meant decisions about his care could no longer be made by his family, and would be made by doctors.

He was moved to Woodland View Hospital, in Ayrshire, into a psychiatric ward alongside people with serious mental illnesses. He has now been in there for 18 months.

"Everything the family did, Fraser did with us," said his mother Karen Malcolm.

"He had a great life, went sailing, horse riding, enjoyed school, was always a bit of a joker within the family, really just had a great life, very sociable little guy. Loved music."

Fraser's mother Karen says he is terrified he is trapped there permanently

Fraser is one of about 300 people in Scotland with a learning disability or autism estimated to be living behind the locked doors of hospital wards. About 70 are recorded as delayed discharge.

Many of them have been detained under the Mental Health Act.

Fraser's mother Karen said that although he has been in hospital for a relatively short time she is terrified he is trapped there permanently.

She said that when he went into hospital it was in his best interest to get him the help that he needed.

"How wrong were we?" she said.

Karen said Fraser had deteriorated physically and mentally over that time.

"They've taken him on a massive journey on a cocktail of drugs," she said.

She said the family visited Fraser daily but were not allowed into the ward so they could only speak to him through a window.

NHS Ayrshire and Arran said it could not comment on individual patients.

It said: "The appropriate discharge of individuals with learning disabilities following a hospital stay for assessment and treatment is complex.

"It requires patients to have the appropriate support in the community and at times bespoke packages of care to meet their individual needs."

It said it was working on local community provision to prevent hospital admissions.

Changes to the law

The law under which Fraser and most people with autism and learning disabilities are detained and held is currently under review.

The national review was set up by the Scottish government.

Prof Colin Mckay said there are few safeguards once someone has been detained

Colin McKay, professor of mental health and capacity law at Edinburgh Napier, is a member of the review team.

He said that one of the things they have raised as a concern in the Mental Health Act is that safeguards tend to apply at the point at which you are detained.

"Once you have been detained, there are fewer safeguards," he said.

Prof McKay told the BBC that this summer the review team will recommend plans to give mental health tribunals more power to compel authorities and ministers to get people out of hospital and into the community within set timeframes.

Not a cheaper option

Experts say detaining someone in hospital is not a cheaper option either.

Holding someone in hospital is often more expensive than creating a supported place in the community.

Dr MacDonald said often the money was there but it was in the wrong place.

Generally, the cost of someone being in hospital comes directly from NHS budgets.

To create a community place local funding has to be found.

"There is money in the system that supports people with complex needs, it's possible that maybe we're just not using the money maybe the way that we could," she told the BBC.

"Maybe we need to be a bit more flexible with some of the funding."

Dr MacDonald said she has seen examples of people having expensive support packages at first but these have been reduced as they have settled into their new life in the community.

"If we can give people a better quality of life in the community, we will see less behavioural challenges," she said.

Prof McDonnell said he had come across inpatient hospital care costing up to £900,000 a year.

He said this could be provided more cheaply and effectively in the community.

"Basically warehousing people in these settings is expensive, probably not that therapeutic, and people get stuck in the system once they're in for these places," he said.

"You can get into a secure bed very easily. Getting out is another matter."

Mental Health and Social Care Minister Kevin Stewart told the BBC: "Some of the packages that exist at this moment in terms of out-of-area placements, are immensely costly.

"It may actually be a saving in the public purse in bringing folk home with the right support."

What happens next?

The minister told the BBC he was planning a new bill to help tackle the problem and would appoint a commissioner to oversee progress.

He has already pledged to get most people home by March 2024.

A national register is being created because some people have been "lost" in the system.

He said the Scottish government were investing £20m over the next two years.

In relation to people being held in hospitals for decades, he told the BBC: "That situation is unacceptable.

"I'm determined that we do much better here.

"It is vital that we get it right for individuals, because each day that they are away from their family, their friends and their communities, is a lost day."

BBC Disclosure: Locked in the Hospital will be on BBC One Scotland at 20:00 on 15 August.