Hundreds affected by tuition fees residency rules in Scotland

- Published

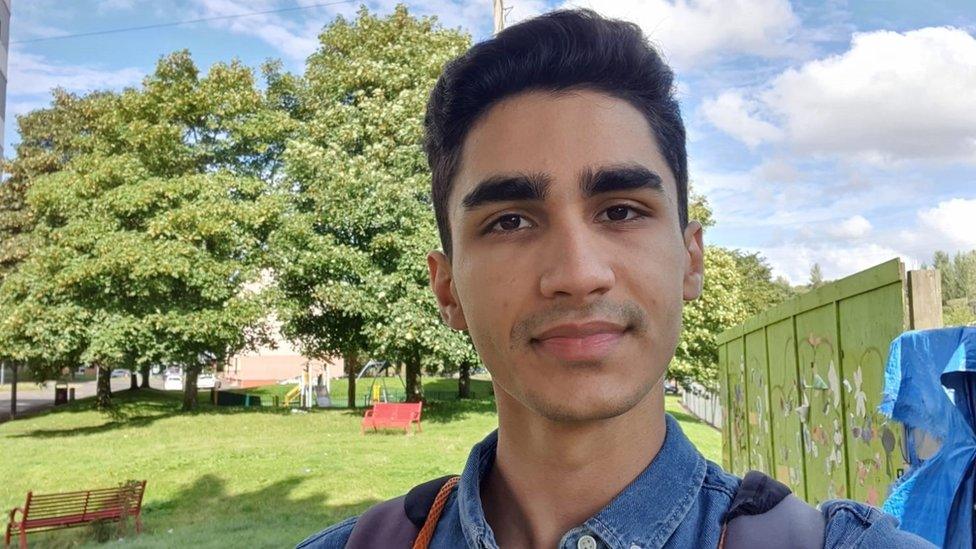

Ahmed Alhindi says he has been left in limbo because of the rules

Hundreds of high-achieving pupils are struggling to access university in Scotland because the rules say they have not been in the UK long enough.

Lawyers are taking the Scottish government to court over the case of one straight-A pupil who has lived in the country for more than six years.

However, she is not getting her tuition fees paid because she is two months short of the length of time required.

The Scottish government said it cannot comment on live cases.

Under the current rules, if you are under 18 on the first day of your university course you must have lived in the UK for seven years to be able to access free tuition.

If you are aged between 18 and 25, you have to have lived in the UK for either half your life or 20 years.

The court case centres on a young woman who wants to study medicine to become a doctor, but missed the required timescale by just two months.

She is being represented by Just Right Scotland, which argues that ministers have not upheld her right to education.

Lawyer Andy Sirel said: "We're taking this case because there's an issue of fairness and human rights at stake.

"Young people who have lived here for many, many years - lawfully - since they were 10 or 11 years old are being denied access to further education purely because of their immigration status."

Lawyer Andy Sirel believes the rules are too rigid

He said these young people wanted to be doctors, teachers, sports coaches, or serve in the Royal Air Force.

"When they finish high school they apply for funding and they're told by the rules, by the Scottish authorities, that they are actually international students.

"Now these are not international students, these are young people who live in Scotland," he said.

Mr Sirel argues that the rules are too rigid and that the Scottish Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS) must be allowed discretion to help migrant pupils access their right to education.

Immigration is reserved but education is not, and he says Scottish ministers could introduce flexibility.

'I feel left out'

Another would-be student, 17-year-old Ahmed Alhindi, says he has been left in limbo because of the rules.

While his friends prepare to start university, he is working full-time as a waiter in Glasgow.

He achieved six As at Higher and two As at Advanced Higher this summer and has unconditional offers from St Andrews, Dundee and Aberdeen to study computer science.

But he has had to turn down all his offers due of the status of his visa.

Ahmed Alhindi says he has been left in limbo because of the rules

"I feel quite left out to be honest," he says.

"We've all had unconditional offers but I'm one of the few who cannot go because of the visa. That makes me feel quite isolated in a way.

"We've done the same subjects, we've been to the same school, we could have went to the same university, but only because of my visa I have been deprived of that opportunity."

Ahmed's family moved to Scotland from Palestine three years ago for his father's new job as a research scientist at Glasgow University.

Because he does not have indefinite leave to remain, he is treated as an international student and would have to pay about £25,000 a year in tuition fees.

He says that is money he cannot afford.

"At this point I am left in limbo, in the sense that I've finished school but I cannot go to university or college and so my only option for the next four years or so is to continue working as a waiter.

"I have no control whatsoever over my future."

He says he will have to wait at least four years before he can apply for indefinite leave to remain and hope to access tuition fees.

Ahmed is now leading a campaign called Our Grades, Not Visas.

'A basic right'

He has joined forces with Just Right Scotland and the Maryhill Integration Network, which works with immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees in Glasgow. They are calling on the Scottish government to provide tuition fees for high-achieving pupils with offers to universities in Scotland.

The campaign has started a survey to ask how many pupils are affected, external. It already has more than 100 responses, including top pupils looking to become doctors, nurses and teachers.

Pinar Aksu, advocacy worker at the Maryhill Integration Network, is working on the campaign.

She says they have members who have been trying to access education for 15 years and who feel their lives are "on hold".

She told BBC Scotland: "Over time, their wellbeing and their mental health is getting worse and worse.

"And in terms of integration, to be part of a community people should have the right to go to university, then find a job if they have the right to work, then be able to live a normal life.

"It's not a lot that people are asking for - it's a basic right, and that is the right to education.

"Where they can't continue to fulfil their dreams, they can't continue to have a normal life. And I don't think people are asking for less or more. They're just asking for their rights."