Mother calls for new law on restraint in schools

- Published

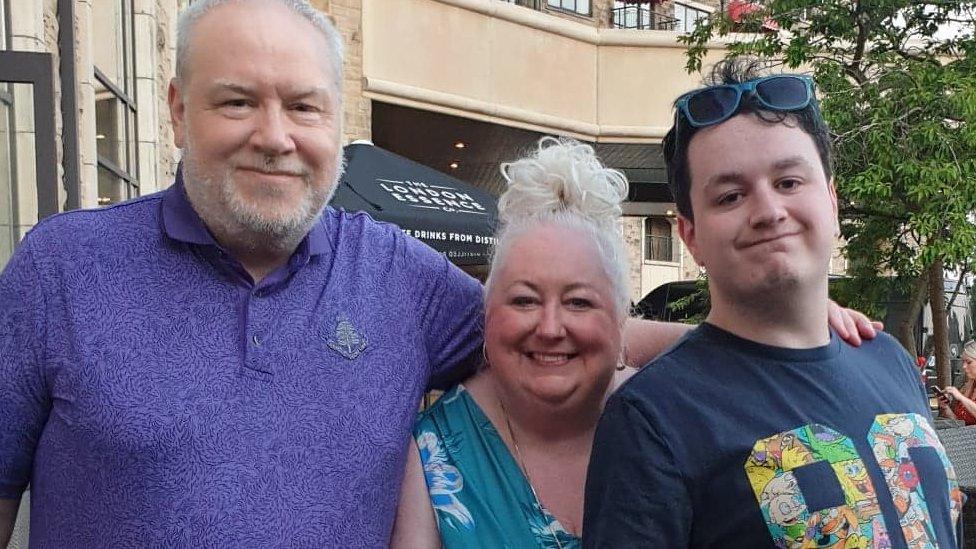

Beth says Calum would tell her every day "please, mummy, no school, school's scary"

A mother whose son was physically restrained at a special school when he was 11 is launching plans for a new law in his name.

Calum Morrison, now 23, has learning disabilities, autism and epilepsy.

His mother Beth said Calum was still traumatised more than a decade later by how he was treated at school.

She wants the current guidelines on physical restraint to become legally enforceable, with mandatory recording and reporting of all incidents.

Ms Morrison also wants compulsory training for all teachers and support staff in how to de-escalate difficult situations and understand children's needs so that physical restraint can be avoided.

"I think the people of Scotland will be shocked to learn that currently there is no law that protects their child being physically and forcefully restrained in school or educational settings," she said.

The charity Enable Scotland is helping her efforts to launch Calum's Law - and Labour MSP Daniel Johnson said he was exploring the possibility of a members' bill in the Scottish Parliament.

The Scottish government said restraint in schools must only ever be used as a last resort.

It added it was exploring options for strengthening the legal framework in this area.

The EIS teaching union said schools were seeking to meet the needs of a growing number of children with complex needs which can sometimes be expressed through distressed behaviour.

It said the focus should be on attempts to "de-escalate" distressed behaviour and teachers needed much more support rather than statutory guidance.

Beth Morrison began campaigning after her son Calum was restrained when he was about 11

Restraint and seclusion, which involves locking someone in a room or safe space, have often been used in educational settings - particularly for children with disabilities and additional support needs.

Ms Morrison told the BBC that since she started campaigning 12 years ago more than 2,500 other families had contacted her because their children had been hurt while being physically restrained.

She said hundreds of cases were reported to her each year and almost all the children who had been injured were of primary school age - and all of them had additional support needs.

"These kids are not naughty," she said. "They're scared. Calum himself says that.

"We have got to make sure the most vulnerable children are protected in law. These kids are getting bruises and broken noses and they're being traumatised."

Calum's family are campaigning for a law in his name

Earlier this year the Scottish government published draft guidance on the use of physical restraint in school settings but parents and Scotland's Children's Commissioner said it was not good enough because it was not legally binding.

Ms Morrison said: "We have been campaigning for change now for over a decade and it's very clear to see that the current approach to non-statutory guidance doesn't work.

"In this day and age, we should have a better understanding of how to work with young people - especially those with learning disabilities - without the use of forceful restraint.

"The experience of this behaviour on young people is traumatising. It affects their social skills, their enjoyment of school and - ironically - their subsequent behaviour at school."

In Safe Hands

The charity Enable Scotland said not enough progress had been made to keep children safe and that the Scottish government's draft guidelines, published in June, were "too little, too late".

Four years ago, the report "In Safe Hands" by Scotland's children's commissioner revealed thousands of restraint incidents, affecting hundreds of children.

Enable Scotland has now published its own report "In Safe Hands Yet?" which says children are still not protected.

Jan Savage, the charity's director, said: "In simple terms, the rights of children and young people in Scotland are still not protected and it's unacceptable."

She said that four years after the investigation by the children's commissioner draft guidance was just not good enough.

"Action is needed to protect children's rights in law, and to set out a clear strategy for systematically reducing restraint and seclusion in Scotland to a point where it is no longer a feature of our education system in Scotland," Ms Savage added.

A EIS teaching union spokesman said: "Guidance needs to be clear and accessible to staff who increasingly are struggling to cope with increased levels of distressed behaviour by children, against a backdrop of large class sizes and cuts to education staffing and budgets.

"Teachers, schools and young people need much more support than they are getting. The EIS does not believe that statutory guidance will ensure that vital support. Rather, it risks an unnecessary further drain on already stretched resources."

- Published17 June 2022

- Published2 October 2018

- Published9 April 2017