One in six patients should not be in hospital

- Published

Fay Rosine's hospital discharge was delayed to allow support to be put in place

Record numbers of people are experiencing long waits in emergency departments because hospital beds are full and doctors are struggling to get patients out.

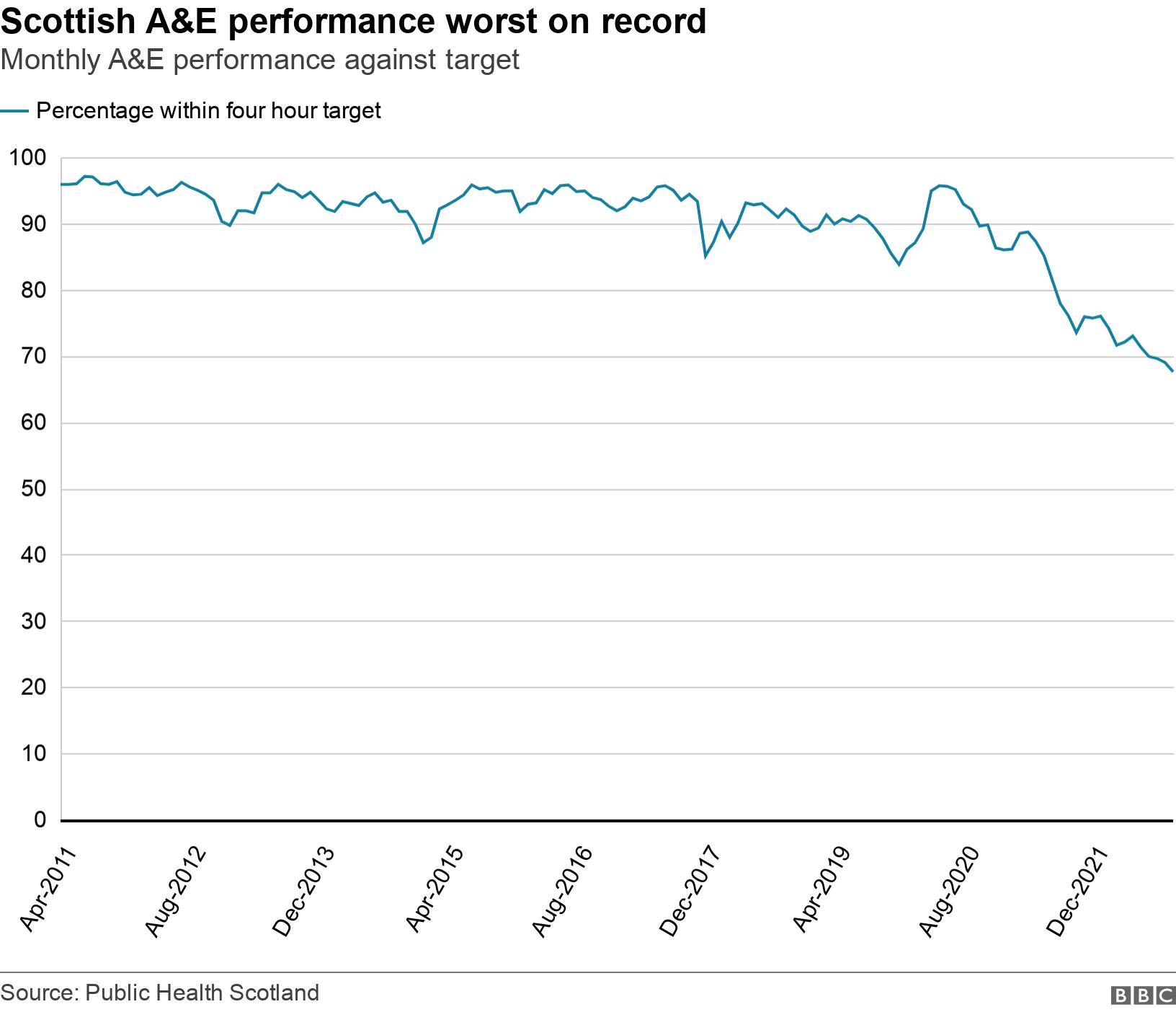

NHS statistics published on Tuesday show that A&E waiting times in September were the worst on record, external.

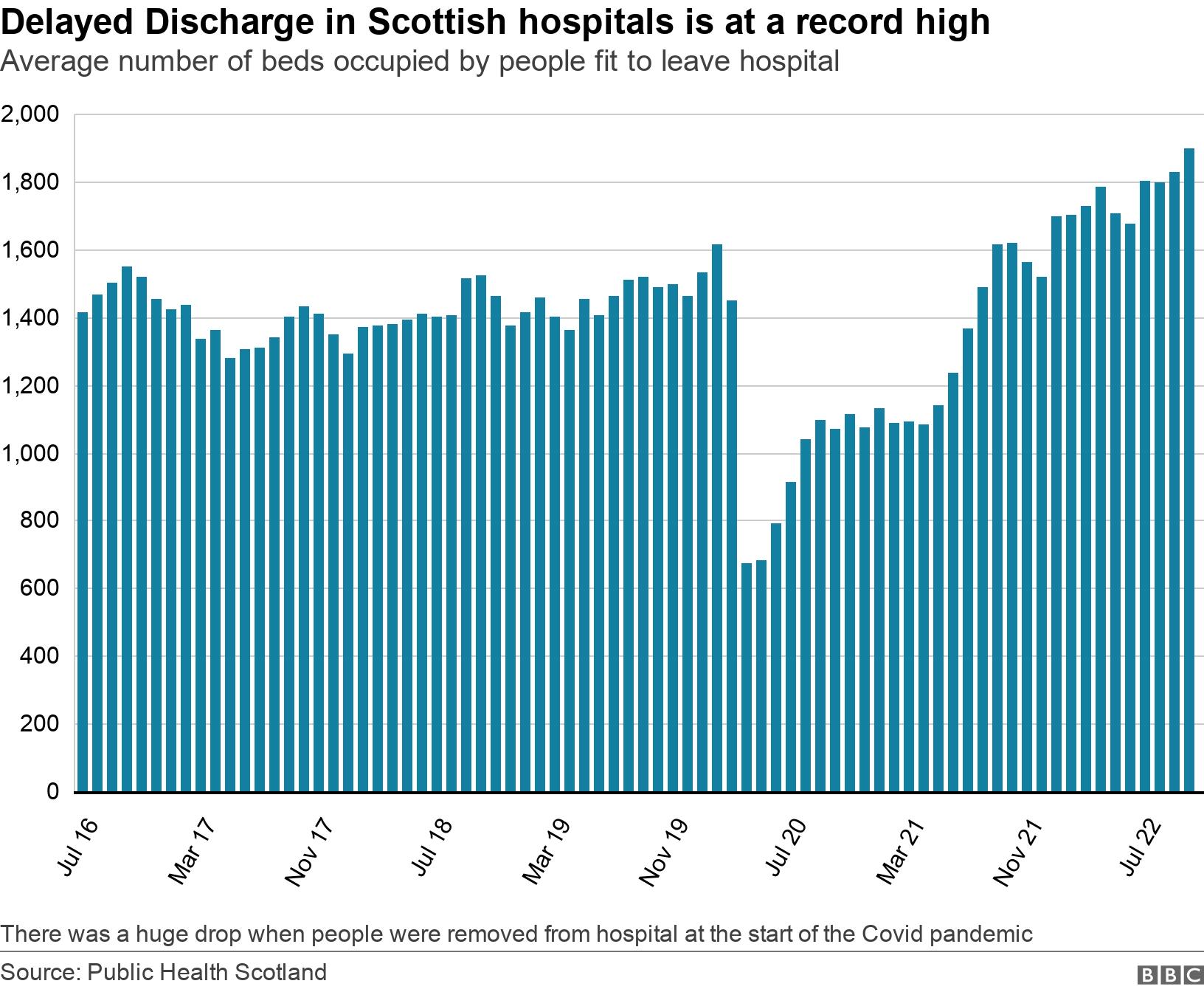

Separate figures also showed that the average number of beds occupied by people who had no clinical need to be in hospital was also at a record high, external.

Edinburgh Royal Infirmary (ERI), one of the busiest hospitals in Scotland, is a prime example of the problems facing the NHS.

It has 876 beds but on the day we visited 137 were occupied by patients who were clinically ready to be discharged.

That is almost one in six beds taken up by someone who could be sent home or moved to care elsewhere if suitable support was available.

The latest NHS data suggests the picture is similar across the country with 1,832 of Scotland's hospital beds occupied by patients who could be discharged.

Fay Rosine is one of those patients who was delayed leaving hospital because she needed a package of care to help her live independently at home.

The 79-year-old ,from Prestonpans, was in ERI for four weeks after she fainted in the shower at her home and spent the night on the floor of the cubicle.

Her neighbour raised the alarm but it was the window cleaner who found her and called an ambulance to take her to A&E.

Fay was treated for the cuts and bruises from her fall as well as her blood pressure and diabetes.

However, she could not go home because she needed to work with physiotherapists to improve her strength so she could tackle the stairs in her house.

She would have also needed carers to come in regularly to provide assistance.

"I don't like depending on people," she said. "I've always been an independent person but I know I can't go back to being totally independent."

Fay eventually moved into assisted living accommodation because her house was unsuitable.

Most hospitals in Scotland face issues getting people out when they are medically ready to go home.

Figures for July, August and September 2022 showed the highest average number of beds occupied due to delayed discharge since guidance came into place in 2016.

And this difficulty getting people out of hospital leads to delays getting people in.

The emergency department at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary is routinely the busiest in the country.

It has capacity for 37 patients but often has to make room for double that.

Of 2,265 people who attended A&E there in the week to 16 October, less than half were dealt with within the government target of four hours.

Acute Medical Director Dr Caroline Whitworth said the average wait for those patients who needed to be admitted was eight to nine hours and some will wait much longer than that

Dr Whitworth said the aim was to get patients into hospital to get the medical care they needed by the right people and to allow them to leave hospital quickly.

But at each stages there is a block, she said.

"The occupancy is above 100% at times, at the moment we have more patients in the hospital than we have beds and so it affects everyone," Dr Whitworth said.

"There is no two ways about it, about one in six beds are occupied by patients who are not getting home and could get home and that's what is creating the pressure."

Prof Emma Reynish said staying in hospital was detrimental to being able to recover from an acute illness

Prof Emma Reynish, a care of the elderly consultant at ERI, said hospital was not always the right place for people to be.

She said staying in hospital was detrimental to being able to recover from an acute illness, with it having a negative effect on their muscle strength and mental wellbeing.

Prof Reynish said it was important for people to return to their usual routine as soon as possible.

Edinburgh faces particular challenges with delayed discharge and the local authority figures are the highest in the country.

But the reasons behind the problem are similar across Scotland - a significant shortage of carers and community health workers, as well as older patients whose needs are more complex.

Michelle Jack says discharging a patient from hospital is 100 times more complicated than admitting one

Michelle Jack, associate nursing director at ERI, said: "Discharging a patient from hospital is 100 times more complicated than admitting a patient to hospital."

She said there was always lots of discussion about whether patients were safe to go back to the same environment they came from.

"Do they need social work input? Do they need physios or other health professionals to make sure that patient is safe to go home?" she said.

"Also are the families and carers happy to have the patient back to that home environment and can they manage the patient in that environment?"

Efforts are being made to overcome the disconnect between health services and social care services which can slow down a patient's discharge.

NHS Lothian has introduced a new system "discharge without delay" meaning that from the moment a patient arrives in hospital a team starts working on how to get them home.

Social Care staff are based in the emergency department and on wards.

The hope is that it can reduce the length of stay for patients by several days.

Abi Sayo works with elderly patients to ensure they have options when they leave hospital

Abi Sayo, a social worker who works with elderly patients, said that during their hospital stay they explore options for care when they are ready to go home.

"The social worker is the link between the community and the individual," she said.

"We are looking at the social issues in the community as opposed to the medical needs. So once the medical needs are met, we are looking at how we can meet those needs to help them lead that fulfilling life."

There is a recognition that this winter will be extremely tough and the Scottish government has promised £600m to ensure that people can be cared for at home as much as possible and to avoid unnecessary admissions.

It said retaining and recruiting additional staff would be a key part of that but high vacancies were a long-term problem with no obvious short-term fix.

Mike Massaro-Mallinson, director of operations for the Edinburgh Health and Social Care Partnership, said there were many reasons why demand was outstripping supply in social care but the biggest problem was staffing.

To fix the long-term shortage of workers there needs to be a shift in our attitudes to caring as a career, he said.

"It's such a rewarding job in terms of providing care for people in their own homes," Mr Massaro-Mallinson said.

"It is a real privilege so there is something about how we value care and have that recognised in society at this point in time but the reality is that we need more."

Related topics

- Published20 September 2022