Striking use of Holyrood’s tax powers

- Published

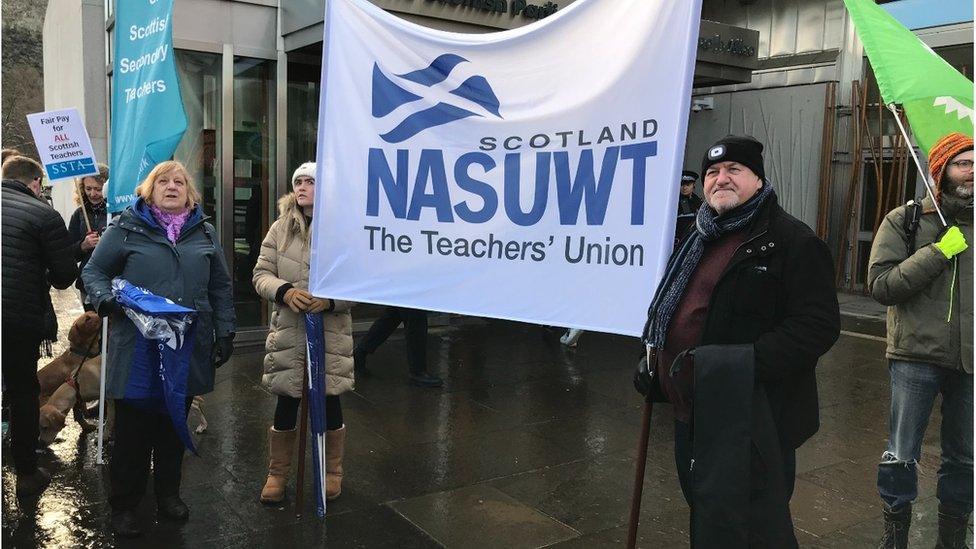

Scottish trade unions have been lobbying for bigger pay rises next year

Public sector workers are better organised than those in the private sector for strikes and they have fallen further behind in real wages, helping to explain the wave of stoppages and Thursday's lobby of Holyrood.

When ministers say inflation-linked pay rises are unaffordable, Scottish trade unions now have an answer: use the Scottish Parliament's powers for a big increase in tax revenue.

Ahead of next week's Holyrood budget, unions have published a study of how tax powers could be used to load lots more on to higher earners, widening the tax net, reforming or replacing council tax, and making the case for a wealth tax.

Like an advent calendar of pay disputes, there's someone on strike in public services every day until Christmas, and they go on into the New Year.

Open today's door and you'll find Scottish teachers. Then it's Royal Mail, again.

Next week, rail workers return to strike action, along with driving test examiners in Scotland, and Highlands and Islands airport staff.

Just ahead of Christmas, Glasgow is one of the airports where inbound passengers will find hold-ups due to striking Border Force officials.

Among the most controversial and consequential stoppages will be nurses and paramedics in England.

Why the public services? Here are three reasons:

They are a lot more unionised than the private sector. And where unions are strong in the private sector, it is in sectors which were previously publicly-owned.

They are dispirited. Recruitment difficulties and jobs left vacant affect those left behind, struggling to fill the gaps, yet finding backlogs have built up and delays lengthened. The auditor general warned this month of the mental health toll on public sector workers, and called for a comprehensive workforce plan.

They are falling behind. Public sector pay held firm during the pandemic while others were put on to 80% furlough rations but government workers have been cut adrift from private sector pay increases during this year of rising inflation.

Private sector employer, who are employers struggling to recruit and retain the workers they need, have more flexibility to put up pay in response - and are able to pass on at least some costs to customers.

The most recent figures from the Office of National Statistics show average public sector pay rising 2.2% in the year to the July to September quarter, while private sector pay was up 6.6%, not including bonuses.

Taking inflation into account, both sectors were worse off, but those in government service by much more. And since those pay figures for late summer, consumer price inflation has risen steeply, meaning real earnings will likely be shown to be further down.

'Oh yes they are'

Today at Holyrood, Scottish trade unions have been lobbying for bigger pay rises next year. Most of the disputes taking place now are for pay rises in this current 2022-23 financial year.

However, today's focus is on the public sector pay policy to be announced next week by John Swinney, the interim finance secretary, alongside his draft budget for 2023-24.

Teachers are among the Scottish public sector workers striking over pay

While sympathetic to public sector workers, Scottish ministers point to the cuts Mr Swinney has had to apply to non-payroll services in order to enhance pay offers. But further pay claims are "not affordable", says the Scottish government.

This being pantomime season, the answer from the Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC) this week is "oh yes they are… and here's how…"

The umbrella body for labour unions has published an analysis of what powers the Scottish government has to raise more funds in tax, and how much they could bring in.

This is a sort of reverse engineering of public finance. It starts with a hope for at least a 12% increase in the public sector payroll budget, just ahead of price inflation, and then finds ways that could be funded.

To those who like taxes, particularly those who like raising taxes and in progressive ways, that journey makes for quite an exhilarating read. For those on higher earnings or with a lot of wealth in physical, financial or pension assets, it might be wise to take a seat before reading on.

To get to the kind of funds the STUC has in mind to fund its pay demands, its report - compiled by economic modellers at Landman Economics consultancy - starts by finding ways the public payroll could partially pay for itself.

From higher pay for public sector workers come higher income tax receipts for the Scottish government, and higher National Insurance contributions for the UK one.

So while pushing up the public payroll bill by 10%, or £2.4 billion, the net cost to the Scottish government can be seen as 76% of that or £1.8 billion. And including the payback to the UK government coffers, the net cost falls to 57% of the gross figure, or £1.4bn.

Behavioural effects

Then the tax increases begin, starting with the Scottish government's main fiscal lever, income tax.

The freezing of thresholds is a form of stealth tax as people's earnings rise through them. They look likely to remain frozen next year in Scotland, as they are doing with Jeremy Hunt at the UK Treasury. With high inflation, that 'fiscal drag' brings in vast amounts of money with minimum political pain.

But the union paper goes further, looking to reduce the higher rate threshold from £43,663 to £40,000, meaning the net goes wider still.

With rates on above-average earnings already one penny in the pound higher than the rest of the UK, the STUC paper suggests that rises to three pence more. So higher rate tax, currently paid on earnings above £43,663, would go up from 41 pence in the pound to 43 pence.

The threshold for top or 'additional' rate tax would fall to take in earnings above £125,000, while the rate rises to 48%. And a further tax band would kick in from £75,000, at a 46% rate.

John Swinney is covering the finance brief while Kate Forbes is on maternity leave

How much could that bring in to the Scottish government budget? A lot depends on how people respond.

High earners have bigger incentives, and better accountants, with which to switch earned income to unearned dividends (taxed from Westminster), so there would be a 'behavioural effect'.

But it's very hard to say how big that would be. The more taxes rise, the bigger it would be.

This modelling arrives at a figure of £387m from lowering the higher rate threshold by £3,663. The new band, between £75,000 and £125,000 could bring in £200m.

Adding two pence in the pound to that rate and the ones above could bring in £220m. And with some more gains elsewhere - modest because there aren't that many very high earners in Scotland - the total comes to £867m.

The modelling further suggests that the top 10% of earners in Scotland would be nearly 3% worse off. That's from the income tax measures. There are plenty more ideas for squeezing the rich.

Council tax, for instance, is widely acknowledged as being ripe for reform and far from progressive. The proportion of income paid by low income households on income tax is higher than the proportional impact on those paying council tax on big homes.

Measures that could be introduced swiftly would be slashing the reduced council tax rates on second and holiday homes, as well as empty properties. Then slap a surcharge on the most valuable quarter of homes, or perhaps those valued at more than £500,000.

That could be progressive on those in the top half of earners, but oddly, it would not be progressive in the lower half. Some in big homes have low income.

Longer term, by which they mean it's possible by 2025, council tax could be replaced by a Proportional Property Tax, meaning bills are directly related to the value of the property. Something similar was proposed 16 years ago by an independent review commissioned by Labour ministers from a panel led by a senior banker.

So, for example, if everyone pays 0.7% of the value of their home, that's nearly £1,500 a year on the average owner-occupied home. And the STUC/Landman reckoning is of nearly £1bn more income than council tax currently generates. For a house worth £1m, that means a £7,000 annual bill, which is a lot more than the owner is currently paying.

Frequent flyers

But they're not finished with the high earners and wealthy yet. The jackpot of STUC tax reforms would be a wealth tax.

The illustrative examples suggest that one in eight households have wealth of more than £1m. Get each of them to pay 1% in cash each year, even though some are cash poorer, and the annual bill would be shy of £8,000 per average house, bringing in £1.3bn.

Or try setting the threshold at £2m in wealth, which would mean tax bills averaging nearly £18,500 for 2.2% of households, bringing in an extra £500m annually.

Or push it up to £10m - the seriously wealthy, and only 0.1% of households. A 1% tariff would mean a bill of £74,000 per year, and £55m for public coffers.

But it's at those levels of wealth, along with higher council tax and much higher income tax that you would see most behavioural effects - tax avoidance by clever accounting, moving out of Scotland, or not moving into it.

Administrative costs, it is acknowledged, would be high - perhaps 1% of takings, if a register of wealth is to be reliable. And there's a further big catch. The STUC 'fairer tax' paper takes the powers the Scottish government already has, which is intended to deny ministers the opportunity to point the finger of blame and responsibility at Westminster.

The Scottish government could not introduce a wealth tax under its current powers. Yet it could empower local councils to do so. And that would make it a much more politically and administratively complex challenge.

The STUC isn't finished there. It has briefer suggestions of a Land Value Tax applying to businesses, while scaling back the Small Business Bonus tax holiday for the past 14 years. It is at growing cost in revenue foregone, and with little to no evidence that it makes much difference to economic or employment growth.

There's encouragement for use of tourist taxes and a frequent flyer levy is suggested on top of passenger tax.

And if some of those are more difficult to introduce next financial year, the report points to council reserves as a short-term piggy bank to be raided ahead of these new sources of revenue coming on stream.

Would this plan work? It would be very challenging to introduce, and could be laden with unintended consequences for economic growth and total tax revenues, perhaps going far beyond the assumptions in the economic modelling used.

It is an audacious pitch that all of this extra revenue should be shovelled into the bank balances of public sector workers, and not into other elements of public funds, such as welfare benefits or capital spending on better quality infrastructure.

Politically, though, it's a clever move by the unions, as an answer to those who say their pay demands cannot be funded, and to those who say Holyrood lacks tax levers. But it's not the unions who would have to persuade voters to back such a plan at an election.

- Published18 November 2022