Mary Queen of Scots: Secret letters written during imprisonment decoded

- Published

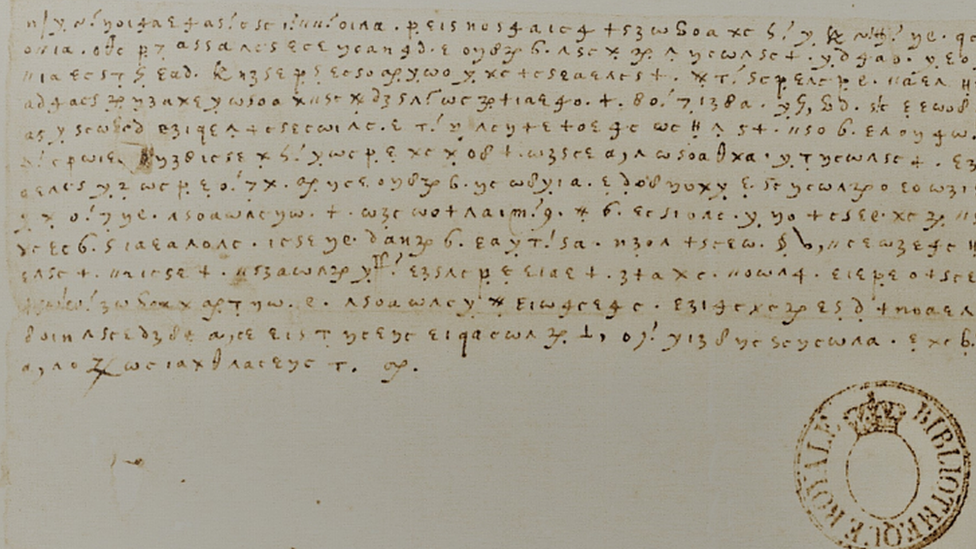

Secret letters written in code by Mary, Queen of Scots during her imprisonment in England have been uncovered and decoded by a team of cryptographers.

The documents, which were believed to have been lost, were found in the National Library of France in Paris.

They were written to her supporters while she was imprisoned by Queen Elizabeth I in the 16th Century.

Experts said the codebreakers' work on the 57 letters was the most significant discovery about Mary for 100 years.

They had been wrongly catalogued in the library, and only when the code was broken was it possible to identify Mary as the author.

Working through a complex pattern of symbols in the letters, they revealed Mary's complaints about the conditions of her detention, her feelings of abandonment by France and attempts to broker her release.

The letters date from 1578 to 1584, a few years before Mary's beheading 436 years ago - on 8 February, 1587.

'This is too crazy'

Dr George Lasry, who led the study, told the BBC's Good Morning Scotland programme it was a "fairly complex" process that took about two months, with more than one option for every letter of the alphabet.

"We were expecting Italian because that is what the catalogue said, but then we started to see some French words - 'ma liberté' (my freedom) - and sentences no-one would write if they were free," he explained.

"So we knew it was someone in captivity, and some of the language was in feminine form, so it was a woman. She also wrote 'mon fils' - my son - so it was a woman in captivity with a son.

"We thought 'this is too crazy', it can't be Mary Stuart. But then we saw the word 'Walsingham' and we knew Francis Walsingham was the spymaster of Queen Elizabeth I, so we concluded it was from Mary.

"It was very difficult to believe at the start so it was a very exciting moment."

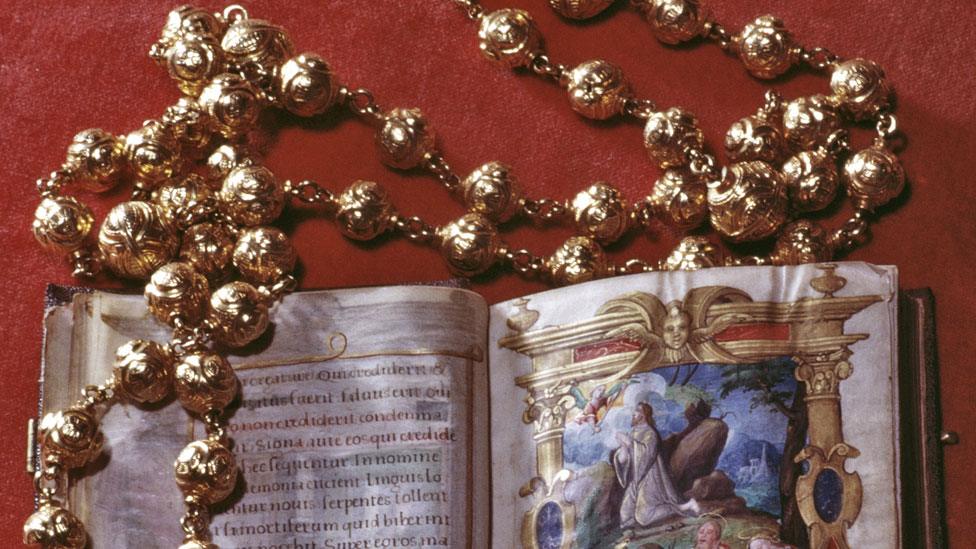

The romantic, doomed figure of Mary Stuart lived out the last 19 years of her life in English captivity.

Despite close surveillance, she was able to pass out the secret letters to her supporters via some trusted courtiers who visited her.

The existence of the letters was suspected, but they were thought to be lost

Most are addressed to Michel de Castelnau de Mauvissiere, the French ambassador to England, who was a supporter of Mary, a Catholic.

The existence of a confidential communication channel between Mary and Castelnau was well-known to historians, and even to the English government at the time.

The documents ended up in Paris because their destination was the French ambassador in London.

The existence of the letters was suspected, but they were thought to have been lost.

An international team of code-breakers, which combs online archives for historic encrypted documents, stumbled across them in France's national library.

'Historical sensation'

Dr Lasry, a computer scientist and cryptographer, working alongside Norbert Biermann, a pianist and music professor, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, a physicist and patents expert, uncovered 57 with the same cipher.

The letters also reveal Mary's animosity towards Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I.

She also expressed her distress when her son James - the future King James I of England - was abducted in August 1582.

Mary Queen of Scots was played by actress Emma Snellgrove in a 2018 film about her life

"There is a lot of detail in there about intrigue, politics, her attempts to bribe officials and complaints about her health and conditions in captivity," Dr Lasry added.

"We are just starting to scratch the surface of the content."

Dr John Guy, a history fellow at the University of Cambridge who wrote the 2004 biography of Mary Queen of Scots, said the discovery was "a literary and historical sensation".

"This is the most important new find on Mary Queen of Scots for 100 years," he added.

"These new documents, amounting to some 50,000 words, show Mary to have been a shrewd and attentive analyst of international affairs.

"They will occupy historians of Britain and Europe and students of the French language and early modern ciphering techniques for many years to come."

The authors suggest that other coded letters written by Mary may still be missing.

Related topics

- Published22 November 2021

- Published24 May 2021