Robin Holyrood: Giving to the poor

- Published

A diverging income tax system means higher earners in Scotland will pay a lot more than they would in England, while Scottish welfare benefits get more generous.

The Institute of Fiscal Studies says the poorest households will be £580 better off than they would be in England, and the highest earners, on average, £2590 worse off.

However, such changes come at a cost - to other public services, and in Scotland's attractiveness to high earners.

The average Scottish household will be £210 worse off next year than it would be on similar income in England.

That's after accounting for different Scottish rates of income tax and different levels of benefits.

For the average household, it's not a huge difference. And it helps to pay for those extra benefits from living in Scotland: university tuition fees paid by the Scottish government, more generous social care, free bus travel for younger and older folk, NHS prescriptions and eye tests, and so on.

While the average tax impact is modest, it's at the margins that you can see something more significant going on. The highest earners are paying quite a lot more in tax. The lowest income households are doing better from benefits, particularly those with children.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney has proposed an increase in the tax rate for higher earners

In other words, Scotland is becoming markedly more progressive than England - meaning re-distribution from the well-off to the poor. We now have figures to show how much.

This is an important indication of how much devolved powers are being used by Holyrood. It's often criticised for not making more use of its powers to make a difference.

On this count, big choices are being made, rebalancing in favour of poorer Scots and of children. Whatever else Nicola Sturgeon can claim as a legacy (when the time comes), taking from the most prosperous and giving to the least well off is very likely to feature prominently.

Mind the gap

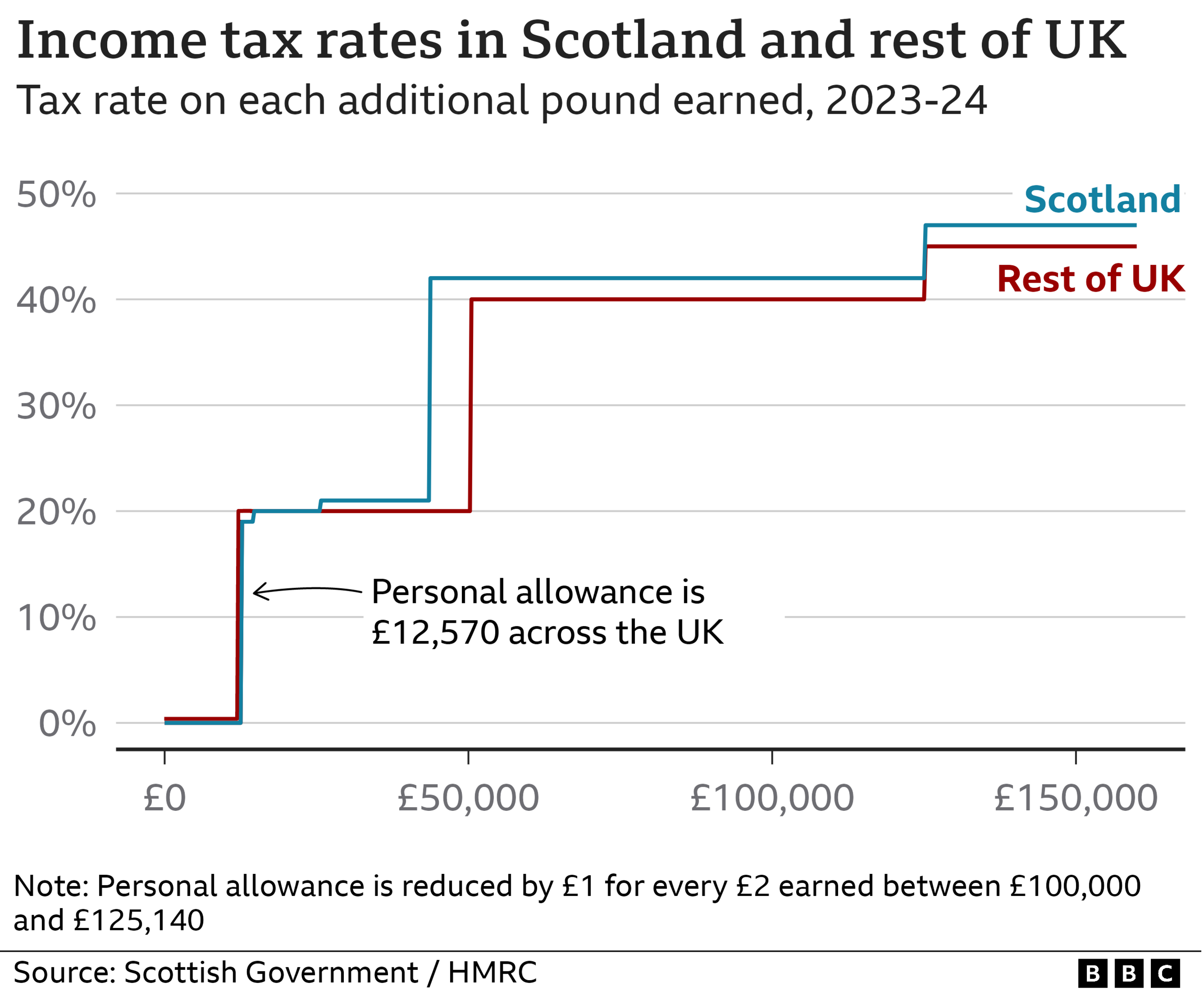

First though, a reminder of what's already in place for Scottish income tax: those earning up to around £28,000 pay around £20 less than in England each year. You could consider that to be merely a gimmick, allowing ministers to say Scotland has the lowest income tax rates in the UK.

At higher incomes, there are higher tax bills than south of the border. With a £50,000 salary, it's £1,550 higher, not only because tax is currently paid at 41 pence on the higher rate instead of England's 40 pence in the pound, but because the threshold for that higher rate has been frozen in Scotland.

The higher rate kicks in at earnings above £43,663, while that threshold has been raised above £50,000 in England. The difference between the two is paid in England at 20 pence in the pound.

If MSPs vote through the tax rates proposed by John Swinney, the Scottish finance minister, those rates will go up on higher earners to 42 pence in the pound for higher rate tax. Also, the additional rate threshold comes down from £150,000 to just over £125,000 (likewise in England) with the top rate in Scotland going up by 1 pence to 47 pence in the pound (45p in England).

The distributional effect of this has been calculated by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, that London-based hotbed of tax and benefit analytics. It has recently been taking a close interest in Holyrood's divergence on income tax and welfare. You may have seen its warnings about the pressures on council budgets.

The IFS calculates that the tenth of households with the highest income (a tenth of households means roughly 250,000 of them) will be, typically, £2,590 worse off than they would be on similar income in England.

That's not to say the top tenth start as well off as the top tenth in England. The IFS has calculated the average income in that decile and compared it with the same level of income south of the border.

That top tenth may be more likely than others to gain from getting university tuition at no cost. But that's not the kind of benefits that the welfare boffins were measuring.

Child payment

They looked at the way in which the Scottish government has used its new-ish powers over welfare benefits since they began to be devolved in 2017.

The big increases arrived last financial year, 2021-22, when around £3bn was re-allocated from the Department for Welfare and Pensions and to the Scottish government. That does not include the state pension or universal credit: it does include family and disability benefits.

Scottish Child Payment was first introduced in 2021, for low-income families with children under six

That has allowed Scottish ministers to re-design some benefits and make them more generous. So we've seen the introduction of the Scottish Child Payment - rising to £25 per child per week for families already on means-tested benefits, and extending from those aged up to five to take in children up to 16. There's no similar payment in England.

The IFS calculates that provides an additional £580 per year, on average, for the 250,000 or so households with the lowest incomes.

For those on lowest income, that means an increase of 4.6% in annual income. For those in the highest tenth, the extra Scottish tax hit averages 2.1% of income, while the £210 average hit to disposable income comes to 0.5% of the average.

Rising disability claims

That low-income decile includes a lot of older people and single people. But without children, there's only a very modest gain in income.

When you focus on families, which is what Scottish ministers have chosen to do, the gain is far greater. The IFS says the average family with children in the 30% of households with the lowest income will be better off by £2,000 a year than in England.

A typical out-of-work lone parent with two children, after housing costs, will have her or his income raised by 19% as a result of the Scottish child payment.

Changes to disability benefits have been slower and more complex to roll out, but ministers plan for these also to be more generous than in England - by an estimated one-fifth. That can be expected to add to the progressive nature of these changes, as people with disabilities are more likely to have low incomes.

The IFS notes that there is a significant increase in applications for disability benefits on both sides of the border, and the success rate of these applications has stayed at similar levels.

So the cost of disability benefits is rising for both governments. And if Holyrood is to be more generous, the cost will rise faster.

Regressive council tax

Of course, cost is the other side of this. Funds raised from Scottish rate income tax payers are not only for redistribution through the benefits system. They also have to meet expectations and commitments across the full range of public services.

Funds channelled into progressive policies on welfare benefits are funds that cannot be spent on health, schooling, policing or social care.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC), among others, has made clear that these choices have unwelcome consequences for other bits of the budget, while the health service is also devouring an ever-growing share of Holyrood's budget.

The IFS shares with the SFC a keen interest in the potential loss of revenue if high earners are squeezed too hard. For some high earners paying Scottish income tax, salaries can be turned into dividends, which are taxed by the UK government.

Ultimately, high earners can move out of Scotland if tax bills become too high. As I argued when the draft budget was published in December, there may be less of a problem with people moving out of Scotland and more of a difficulty over time in attracting high earners such as doctors into the country, if Holyrood grows a reputation for ratcheting up tax to pay its bills.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests that the time is coming when higher revenues may have to come from other sources, such as council tax.

It has long argued that council tax is far from progressive. The share of income it takes from those living in valuable properties is far smaller than the share of income taken from those in the least valuable homes. And the value of your home is not directly related to your ability to pay a monthly or annual tax.

However, more than 30 years on, and with property valuations still stuck in 1991, the council tax is barely reformed. From today, councillors are deciding how much they can raise it this April, in a bid to protect their services.

Related topics

- Published16 December 2022

- Published15 December 2022

- Published16 December 2022