What is Nicola Sturgeon's report card?

- Published

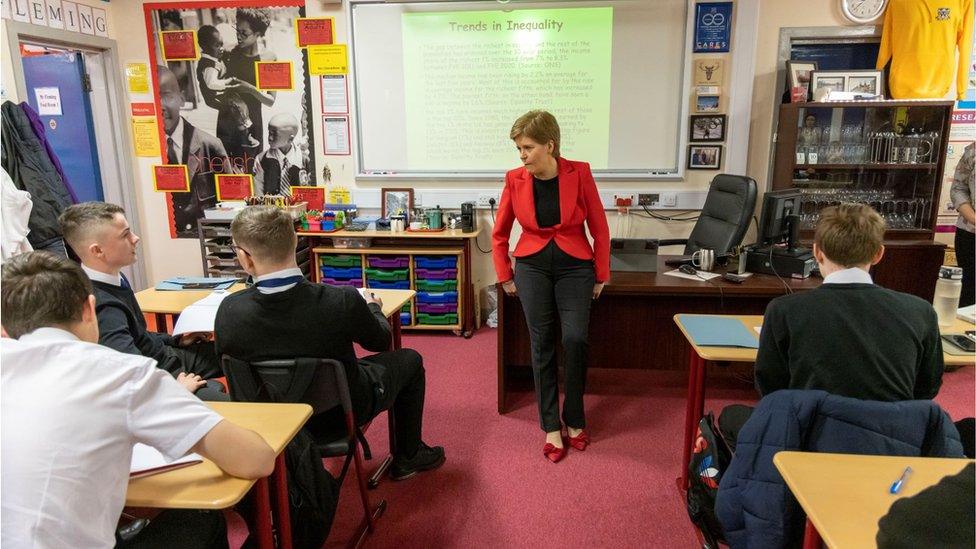

Nicola Sturgeon often said that education was a top priority for her

Nicola Sturgeon has been Scotland's first minister for more than eight years, the longest anyone has stayed in the post.

As her time at the top of Scottish politics comes to an end, BBC Scotland correspondents look at how she has done in their area.

Nicola Sturgeon became first minister in the wake of the failed independence campaign in 2014, stepping in after Alex Salmond's resignation.

Her tenure will be remembered for many things but in the end she has not moved the dial on the founding issue which got her into politics - Scottish independence.

Ms Sturgeon took charge of a nation divided on the issue and will leave Bute House with the polls still broadly split down the middle.

She faced off with five different UK prime ministers - all Tory - but none would grant her a second crack at a referendum. In her opinion, a democratic outrage.

A Supreme Court case proved another dead end.

Ms Sturgeon has now decided to release the reins at the very moment where the next steps will be mapped out.

She has not given up on her dream of independence but it will be for someone else to decide the strategy and lead the campaign.

Before she was first minister, Nicola Sturgeon spent five years as health secretary.

In that time she made plenty of big calls - scrapping prescription charges, introducing minimum pricing legislation, a 12-week legal requirement to treat patients.

She was also involved in the early days of building the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow.

As first minister she'll undoubtedly be remembered as the woman who led Scotland during a global pandemic - fronting televised briefings and occasionally deciding that Covid rules would diverge from other parts of the UK.

But you are never far away from controversy when it comes to handling of the NHS.

There are record waiting times to access NHS treatment and high levels of staff vacancies - as well as the ongoing Hospitals Inquiry and the Scotland and UK Covid inquiries.

These could provide some uncomfortable verdicts on decision-making by Nicola Sturgeon's government.

Education was a top priority for Nicola Sturgeon when she became first minister.

Helping more young people from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds to do better at school and get to university was to be a defining mission.

However, her term ends with the first national teachers' strike since the 1980s and strained relations between the Scottish government and the teachers' unions.

Closing the attainment gap, another goal, was always going to be a complex, long term task.

Universities are now taking in a record number of students from the most disadvantaged parts of Scotland, but there are worries that other young people may be finding it harder to get on to certain courses.

Progress was being made closing the attainment gap in schools. Then came the pandemic and unthinkable disruption to the education system.

Supporters of the government can point to the progress being made helping children from the most disadvantaged areas before the pandemic.

But until the teachers' pay dispute is resolved, the risk is that the shadow of picket lines will hang over discussion about education itself.

It can be argued that Nicola Sturgeon's biggest single contribution to Scotland's justice system is her announcement of the abolition of the "not proven" verdict.

The undefined second verdict of acquittal, unique to Scotland, has caused angst for decades, if not centuries.

But depending on when she steps down, her legacy could also include something far more radical - a pilot of judge-only rape trials currently under consideration by her government.

The first minister portrays herself as a champion of women's rights and such a move would be expected to improve the conviction rate in rape cases.

But removing the right to a trial by jury, even for a limited time on limited basis, would be hugely controversial.

If that's the road the Scottish government decides to go down, Nicola Sturgeon will have played a significant part in making it happen.

The spiralling number of drug deaths in Scotland led the first minister to admit her government had taken its "eye off the ball" when it came to addiction.

Of course, Scotland isn't the only country with drug issues. In many respects, this is an inherited, multi-generational problem.

But Nicola Sturgeon's government hadn't prioritised that problem until 1,000 Scots a year or more were succumbing to addiction.

Before that, local treatment budgets had been cut just as a new dangerous wave of street Valium swept through poor communities.

The issue was particularly acute: Scotland saw seven years of record drug deaths and a death rate higher than any other European nation.

Experts would soon point out that it was comparable with North America's opioid crisis.

There were arguments about who should control drug policy - Holyrood or Westminster - but ultimately, Nicola Sturgeon's government accepted its own responsibilities and declared a national effort to reduce deaths.

Now £250m is being invested into addiction services but Scotland has yet to see a significant reduction in the number of fatal overdoses.

The first minister is a campaigner at heart. The economy has rarely seemed a priority for Nicola Sturgeon, seeing it as a foundation of wellbeing rather than wealth.

She has talked it up, announcing targets for exports, plans for skills and task forces for productivity.

But while focussing her attention on social policy, health and redistribution of income through new tax and welfare powers, she delegated business policy to other ministers.

She took a more prominent role intervening in failing businesses in an attempt to save jobs, with mixed success - an Inverclyde shipyard, a Fife fabrication yard, steel rolling in Motherwell and aluminium in Lochaber. They have created a legacy of higher costs and financial liabilities.

ScotRail was taken over by government. Transport spending shifted to buses. CalMac's ageing fleet is in crisis.

Ms Sturgeon has blocked further private involvement in the NHS. The takeover of Scottish firms and loss of corporate headquarters has been barely noticed across Scottish politics.

Since the COP26 summit in Glasgow, the first minister has argued for higher hurdles being placed in the way of further drilling for oil and gas.

She's urged a faster roll-out of renewable energy but faced criticism for the lack of Scottish content and jobs in it.

Other landmark policies on business suggested her instincts have been for regulation, to tackle other priorities - recently including a freeze on housing rents, the deposit and return scheme for drinks containers, plans to reduce alcohol advertising and to restrict marketing of unhealthy food.

Deciding whether to press on with these will be an early sign of whether her successor plans to change direction and perhaps become a closer friend to Scottish business.

Nicola Sturgeon received international praise for her leadership at and around the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow in 2021.

Though she had no official role, since it was a UK government gig, the first minister used the summit to push forward the climate agenda internationally.

Her government was the first in the world to declare a climate emergency back in 2019 and Scotland's climate leadership has been praised by the architect of the Paris Agreement, Christiana Figueres.

But Nicola Sturgeon's record when it comes to tackling climate change at home has been progressively sliding.

Seven of the last 11 annual greenhouse gas emissions targets have been missed and the Climate Change Committee says Scotland's lead over the rest of the UK has been lost.

Those longer term targets were challenging when they were set but the repeated failures make achieving them an even more difficult job for the next first minister.

No-one could doubt Nicola Sturgeon's dedication to reading, both personally and in schemes like the first minister's reading challenge which offered resources to groups working with young people to encourage reading.

She was a regular guest at the Edinburgh International Book Festival and there can barely be a book festival in Scotland, large or small, at which she hasn't appeared.

But while she's been a champion of the literary world, it hasn't resolved any of the deep-rooted problems that the industry has.

The literature sector, like all areas of the arts, faces a "perfect storm" caused by the pandemic, arts funding cuts and the cost of living crisis.

The wider cultural sector stands perched on that same financial precipice.

Creative Scotland has warned that a third of their regularly funded organisations are at risk in the months ahead if the 10% cuts to their budget go ahead as planned.

The UK-wide Campaign for the Arts Alliance has launched an 11th hour bid to "pull Scotland's cultural sector back from the brink" with an online petition.

Nicola Sturgeon's passion for literature has brought welcome profile to the sector but the reality of this particular chapter in Scottish cultural history looks pretty grim indeed.