Challenges ahead for public finances

- Published

Cancer rates are expected to increase as the population ages

A new report projects the jaws of a big problem opening up over coming decades, between tax revenue and rising demand on public services.

Scotland is not alone. But if the UK bears down on its debt pile, it's going to leave a shortfall in Holyrood of around £10bn.

With or without independence, similar challenges apply. The Scottish Fiscal Commission wants its forecasts to help inform a wider conversation about what needs to happen to economic growth, tax and public services.

Blame it on the boomers, if you wish. The coming few decades are going to be very difficult for public finances.

Put as simply as possible, an ageing population - in scale and duration of lives - is going to demand more of the health service. Healthcare will get ever cleverer about what it can do, raising expectations and also costs.

The ability to pay for that declines as the birth rate remains low and fewer people come into the workforce to pay taxes.

This much won't come as a surprise. But now it comes with some real projections and numbers attached, by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC).

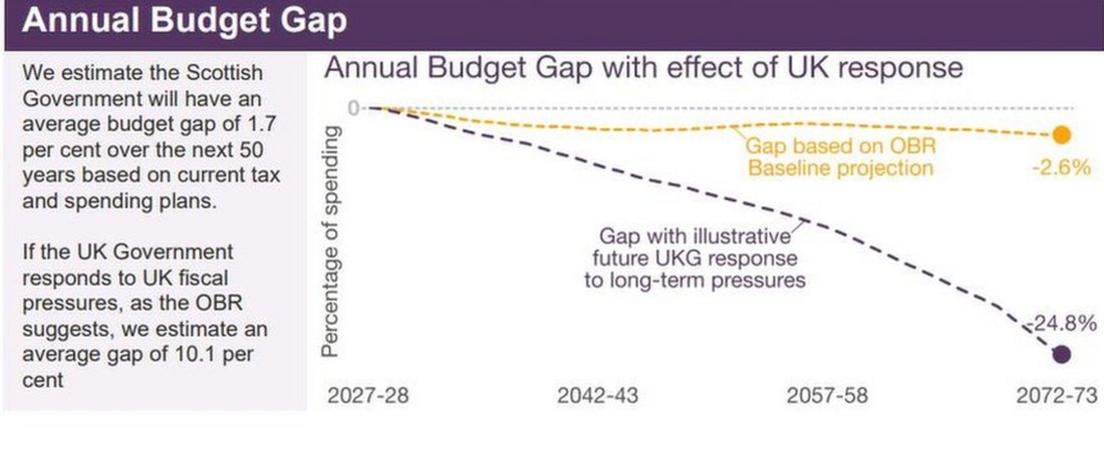

It says the gap between demands on public services and the ability to pay for them will average 1.7% of public spending.

At today's prices, that's a £1.5bn gap in the average year, or 6% of income tax receipts.

But rather than simply adding that gap to the pile of debt, it points out that government has to reduce its debt levels if they are to be sustainable.

If it does that on the scale set out by the Scottish Fiscal Commission's independent advisory cousin in London, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the trajectory for Scottish public spending looks like creating a 10.1% gap between spending and the tax available to pay for it.

That's over the next 50 years. Now, I know what you're thinking: we have very little knowledge of what the next 50 years will hold.

Uncomfortable choices

This stuff requires a lot of ceteris paribus, the Latin used by economists for "other things being equal" or at least staying much as they are.

It follows trajectories for health and other spending, without repairing the damage done to public services in recent years of squeeze. It models the most likely direction for tax revenue, using population demographics.

The assumptions behind this are built around Scotland staying within the United Kingdom until 2072. That may seem unlikely to some, but the SFC makes clear that its warning about sustainable finances extends to any constitutional settlement.

If an independent Scotland is to avoid the widening gap between tax and spend, it would have to grow its economy and tax base faster than the UK and faster than it's been doing.

The means for doing that are either unclear or they require the use of the correct economic levers at the right moment. Some of those levers would have uncomfortable political consequences.

Just one example came yesterday, with the UK government postponing a decision on raising the state pension age to 68. There's never an easy time to do that, and the financial pressure to do it is not going away.

One of the arguments currently being made by SNP politicians is that Scotland requires its own immigration rules, to open the doors to more people, thus growing the economy faster.

That might help, but in the long term, the SFC says it is no silver bullet.

Migrants also require public services. They grow old, and require health and social care.

You could argue that so much is uncertain about the next 50 years that we shouldn't worry ourselves about this report. There may seem to be more pressing needs.

And anyway, some of the pressure comes off after 25 years or so, when the baby boomer generation will be departing. I was born in the final year of the boomers, 1964, and if I'm spared, I'll turn 84 in 2048.

However, the demographic pressures cannot be ignored. As the population is projected to fall by 400,000, the share of it aged 65 and over is due to rise from 22% in 2027 to 31% in 2072. And the pressures will be upon us long before 2072. Indeed, some are already becoming clear.

So if we're to take the pressures seriously, the SFC is telling us that, under current and UK fiscal policies, if public services in Scotland are to continue to be delivered as they are today, Scottish government spending over the next 50 years will exceed the estimated funding available by an average of 1.7% each year.

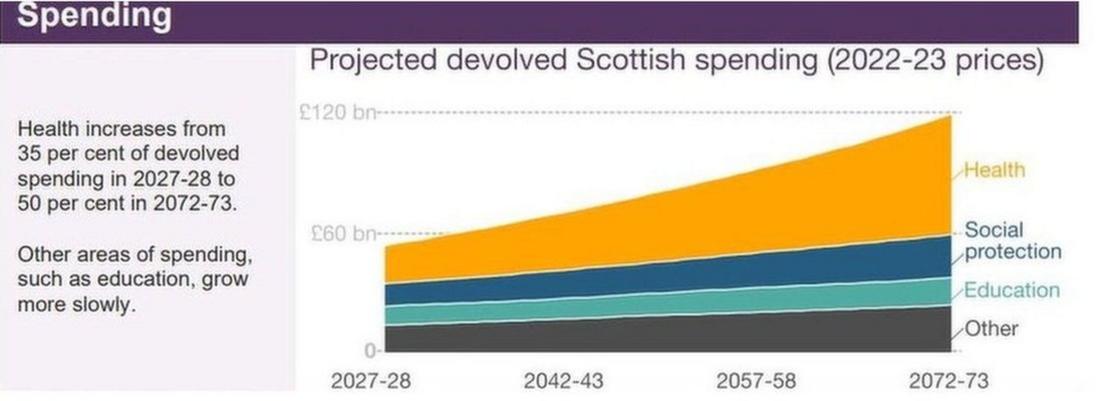

It's forecast that the health bill will rise, in today's prices, from £19bn in 2027 to £60bn in 2072.

With fewer young people, the projected cost of education rises much more slowly from £10bn in four years from now to £14bn in 50 years. Other public services are seen as rising in cost from £25bn to £46bn.

The projection goes further. It takes the OBR warning of the need to bring down UK debt from its current path - rising from nearly 100% of annual national output, to 275%. The bills for servicing that debt are already getting very high, meaning money goes to bond holders rather than public services.

The OBR says a sustainable level would be around 75% of annual output from the economy, or Gross Domestic Product.

So, asks the SFC, what if Westminster does what it's told by the OBR - quite a big "if" there - and squeezes spending as a share of national output so as to bring debt down to those levels.

It is estimated that would lead to Scotland having a gap between taxation and spending equal to 10.1% of that spending bill.

This scenario requires us to assume Westminster makes all the responsible decisions on debt and Holyrood doesn't change much. It's assessing the current constitutional arrangements, where managing debt is not Holyrood's responsibility.

Again, that's quite a big assumption, but stick with this: it's intended to illustrate the scale of the challenge, rather than predict decisions by the many finance ministers there will be in that time.

A 10.1% gap would mean about £10bn of overspend at today's prices, or 26% of the health budget, or 38% of income tax receipts. That's a lot.

Humza Yousaf, Kate Forbes and Ash Regan are standing to replace Nicola Sturgeon as leader of the SNP

So what do we do about it? Prof Graeme Roy, of the SFC, hopes this will lead to a "wider and more informed conversation about the public services available for our children and grandchildren, and the tax policies necessary to sustain these".

There's not much sign of that in the current SNP leadership election campaign. But look ahead to the height of the Boomer pressure on health and care services.

Ash Regan will be comfortably into pensionable age, while Kate Forbes will be 57 and Humza Yousaf will be 62. Their opponents, Anas Sarwar and Douglas Ross, will both be 65.

That's without having to hold others things equal. The ageing process and fiscal future is coming, ready or not.

Today's leadership generation will still be around to face these questions, including: why didn't you do anything about it earlier?

- Published31 August 2022

- Published30 August 2022