The fiscal drag raising the tax take

- Published

Shona Robison is the new finance secretary

A new tax year brings in higher rates of tax in Scotland, as the divergence from UK rates grow wider

Three times as much money is being raised by freezing the higher tax thresholds

VAT hits lower-income households, and a new call has been made for big changes, while questioning whether Holyrood should take on VAT, as currently planned.

A new financial year begins. The reasons for it starting on 6 April go back to the foggy origins of the church calendar but to mark the occasion, it's time to talk tax.

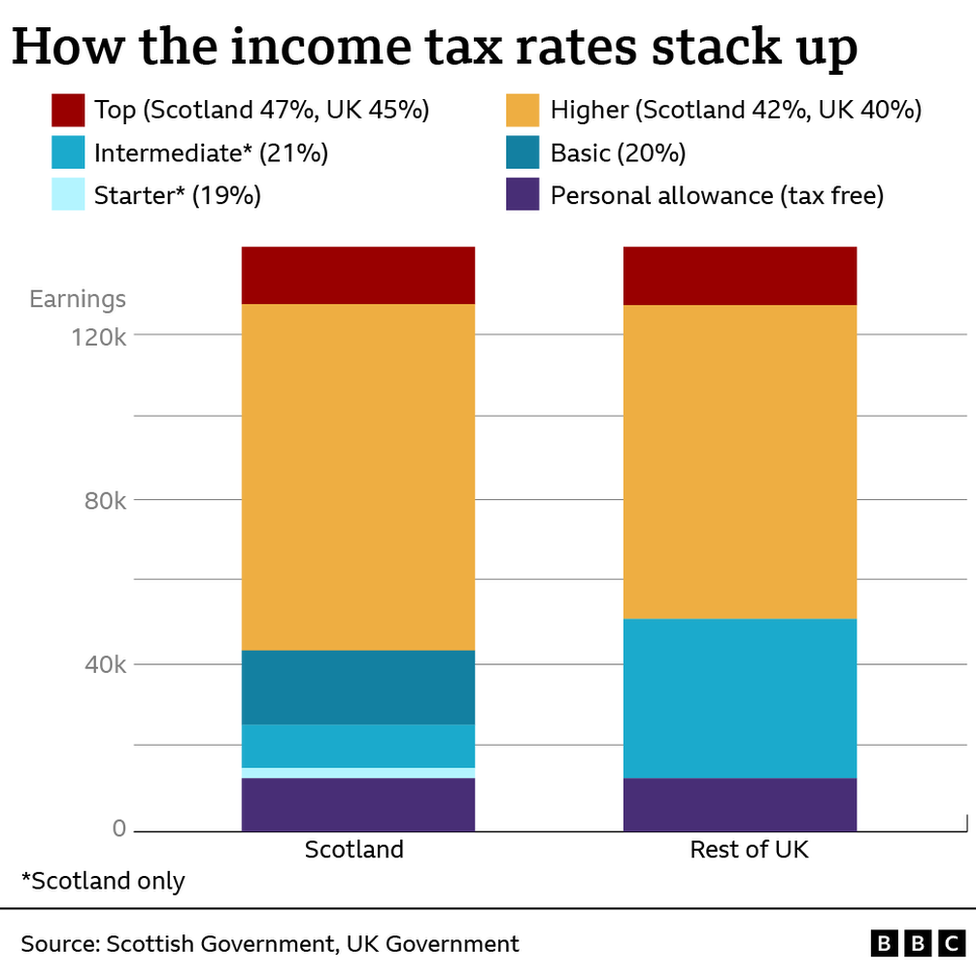

Let's start with the new income tax rates in Scotland for the new 2023-24 financial year.

It's going up for higher earners. If you have income of more than £43,662, every additional pound above that level is now taxable at 42 pence.

That's a rise from the 41 pence higher rate tax band.

Using newly devolved powers, it rose above the rate set at Westminster, which remains at 40 pence.

So suppose you earned £50,000 in the year which ended on Wednesday, and had the misfortune of no pay rise for the new financial year. You'll be paying £63.38 more in the next year - one penny for each of the £6,338 pounds in the higher tax bracket.

While people earning that amount in the rest of the UK pay higher rate tax at 40 pence in the pound and you will now be paying 42 pence, can you assume you'll paying two pence for every pound - £126.76 more? No, you can't.

For the rest of the UK, the Treasury has raised the threshold at which you start paying higher rate tax to allow for wage and price inflation, though it has now stopped doing so.

At Holyrood, that threshold was frozen at or near the £43,663 level since 2016. For the rest of the UK, higher rate income tax starts being paid at £50,270.

So someone - for instance, a teacher in a promoted post - who earns £50,000 in Scotland will be paying £1,552 more than someone on the same salary south of the Border.

And there's more. On that tranche of earnings, that teacher will also be paying 12% in National Insurance Contributions, meaning 54 pence deducted for each pound earned. That NIC rate falls to 2% at Westminster's £50,270 threshold, because it is set by the Treasury.

Top tier tax

The 42 pence Scottish higher rate continues up to £125,140, when the highest tax rate kicks in. That rate will now be charged at 47 pence in the pound, up with from 46 pence.

That 'additional rate' threshold has been brought down for the whole UK from £150,000.

In Scotland, none of this affects your earnings from savings or dividends. These are paid at (lower) UK rates, which creates an incentive for wealthy people (and their accountants) to put a lot of their unearned income out of sight of the Scottish taxperson.

But a medical consultant cannot do that. If she is on earnings of £150,000 this year and last year, the Chartered Institute of Taxation calculates she will be paying £57,561 in Scottish income tax.

That's a tax bill £2,432 higher than last year, on the same pay, and £3,858 more than a consultant doing the same job in England.

Social contract

University tuition is free for Scottish students in Scotland

A big part of the tax story this year, and for the whole UK, is what's called 'fiscal drag'. By freezing that higher rate threshold, with pay rising at an average 5.7% in the year to January, a lot of people are joining the ranks of higher rate tax-payers.

The Scottish government sounds rather pleased about this so-called 'stealth tax', marking the occasion with a media release which points to the £390m it expects to make out of fiscal drag during the new financial year. That is three times the amount, £129m, it expects to make out of increasing the top tax two rates, each by one pence.

The upside to this, says the Scottish government, is that nearly half a billion extra pounds will be raised.

The new finance secretary Shona Robison says this is "fair and progressive, ensuring that those who can, contribute more.

She talks of a "social contract" - more spending on public services and more generous welfare payments than from Westminster. Also, in exchange for paying higher tax, everyone gets free stuff, from university tuition fees to NHS prescriptions.

"The additional revenue will help us invest in our vital public services including the NHS, above and beyond the funding received from the UK government," says Ms Robison.

"At the same time, the majority of taxpayers in Scotland will still be paying less income tax than if they lived in the rest of the UK."

She doesn't say that lower income tax bill is by no more than £22, or that Scots pay more tax than someone on the same pay in England at every pay level above £27,850.

The UK government doesn't sound as proud of its freeze on thresholds, because the impact is newer. With inflation, it's hitting home. And there's less talk of a social contract.

Locking the Personal Allowance at £12,570 (also affecting Scotland) and the higher rate threshold, and doing so from 2021 to 2028, brings in an estimated £13.6bn more in income tax in the next year, and £26.4bn more in 2027-28.

Adding in some extra NICs from employers, the Office for Budget Responsibility points out that is the equivalent of raising the basic rate of UK tax from 20 pence to 24 pence. That's why you'll hear talk of Britain having the highest taxes in 70 years.

VAT man

For lower income households, little of this matters. The main tax they pay is VAT - value added tax - an indirect tax on income at the point when it is spent. It was introduced into the UK exactly 50 years ago, as part of the alignment with the other eight members of the European Economic Community. The initial rate was 10%, falling to 8%. The standard VAT rate now is 20%.

There remains an intention for the proceeds of VAT raised in Scotland to be transferred directly to the Scottish Parliament. This was part of the devolution that brought most income tax powers to Holyrood seven years ago.

VAT is different, though. The Scottish government would not have powers to vary it, or to choose the items on which it is levied. It could not add a higher VAT rate for luxury items (dual rates have been used by the Treasury before), or cut the 5% rate currently charged on domestic fuel bills.

The revenue would be 'assigned' - meaning that all VAT paid by Scots should make its way to Holyrood's coffers. To identify that money remains a big administrative burden. Every VATable transaction would have to be marked as Scottish, or not.

Business would have to make that happen, at a cost. And while it could be relatively easy in shop transactions, it would be much less so with online sales, and least of all where VAT is claimed back by a business.

The Scottish government wants to have greater tax powers, including VAT, but while Scotland remains in the UK, SNP ministers are not in a rush.

Gingerbread man

A report published this week by the Reform Scotland think tank goes into a lot of detail on VAT. It's written by a tax specialist, Heather McCauley, with experience of working in the Scottish government and advising two New Zealand prime ministers.

She has highlighted the unusually high number of exemptions for VAT in the UK. There's food and drink, but with some exceptions. This creates difficult dividing lines. Is a Jaffa Cake a VAT-free cake or a VATable biscuit? And the Office for Tax Simplification is quoted with the mystifying example: "a gingerbread man with chocolate-covered trousers is subject to VAT, but not if it has chocolate eyes".

Also zero-rated for VAT are children's clothing and footwear, books and newspapers. That keeps down prices on a few things randomly deemed to be essential or, at least, worthy. Ms McCauley questions whether the absence of VAT on books is more likely to help higher earners, because they're more likely to buy them.

Likewise, there is zero VAT on private school fees and private healthcare, which do not look much like necessities. There are reduced rates for household fuel and energy efficiency measures (temporarily). Again, higher income households, with more fuel use and more tendency to invest in solar panels, do best out of this.

From the Treasury point of view, it means losing out on about £50bn of revenue. The absence of VAT on food costs the Exchequer £21bn in foregone revenue. On construction of new homes, it's £17bn. And nearly £5bn could be raised by putting up domestic fuel VAT from 5% to 20%.

From a consumer point of view, this would raise howls of protest. But from the hard-nosed tax economists' point of view - and Heather McCauley is not alone in arguing this - it would make more sense to challenge the regressive nature of VAT.

That is, lower income households spend a much bigger share of income on VAT than higher income. By charging VAT on everything, it raises lots more money, and that can be used to offset the increased consumer prices by distribution to those most in need of it.

Provincials

What is striking about her study is how much the UK is out of line with other countries. Not only do others raise a much higher proportion of tax from VAT, but they typically require smaller businesses to charge it.

In the UK, businesses are required to register for VAT when turnover is above £85,000. In other countries, it is much lower. In Japan, it is £5,000. A high threshold creates an incentive to stop growing just below that level, which is in no-one's interests.

Somewhat less attention is paid to the case for pressing ahead with assignment of VAT raised in Scotland. Ms McCauley notes that it is possible, but it's difficult, potentially pricey and doesn't have many international parallels.

The closest is in Canada, where VAT is charged at both federal and provincial level, and distortions are limited because the country's main commercial centres are so far apart.

The report's suggestion is that Holyrood might be wise to park the plans for assignment of VAT within the UK, and to focus on other taxes which would be easier to devolve and more effective in shaping public policy.

That starts with taxes on property and wealth, allowing Holyrood to tax savings and dividend income.