Climate change is harming my mental health

- Published

Jennifer Newall left academia in 2021 after realising she wanted to make an active change

Until two years ago Jennifer Newall was working at the forefront of climate change research.

Her PhD on melting ice sheets and changing sea levels had taken her to Antarctica, Scandinavia and the USA but it was while leading a workshop for primary school children in Glasgow that she began to question what she was doing.

"It dawned on me," she says. "The physics behind this haven't changed in my lifetime. They're not going to change going forward."

Jennifer says she realised action was needed urgently and she no longer had the passion or motivation to continue studying the effects.

She put her career on hold in order to take more direct action but she found the scale of the challenge overwhelming.

Jennifer is one of a growing number of people who have experienced "eco-anxiety" - a chronic sense of hopelessness and fear of environmental doom.

"It presented itself as depression and anxiety," she says. She felt completely paralysed and often unable to get out of bed.

It was during what she describes as her "eco-grief" that 33-year-old Jennifer decided she could not have children.

She says: "I don't feel like I can have children, because a) the world can't cope and b) I would feel guilty bringing any child into this world."

Jennifer plans to set up social enterprise Sain, to help people connect with themselves and nature

Jennifer didn't complete her PhD on the disappearing ice sheets - although she hopes to one day return to it.

She is now living in Perthshire with her mother and has found that mountain biking has helped her achieve some peace of mind.

Jennifer says she plans to set up a social enterprise project in Aberfeldy, called Soulful Adventures In Nature (Sain), to help people improve their mental health through outdoor activities.

She accepts that the climate situation will worsen - but has learned not to feel personal guilt for the circumstances.

"I had the sense of hopelessness and powerlessness. But, thankfully I chose to keep fighting to change that, and have a world that I do want to be a part of," she says.

'Over half think humanity is doomed'

There is a growing recognition that environmental change affects not just physical but also mental health - although there is still relatively little research into the cognitive impact of it.

In 2021, Bath University lecturer, psychotherapist and researcher Caroline Hickman and her colleagues examined data from 10,000 young people, aged 16 to 25, living in 10 different countries.

About half of those who took part in the survey reported feeling sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless or guilty.

The study, published in Lancet Planetary Health,, external found that while threats faced in different countries varied - from food insecurity to pollution or flooding - there were similar levels of anxiety.

"Over half think humanity is doomed, 56% worldwide, 51% in the UK, 73% in the Philippines," Ms Hickman says.

"So there's more closeness in relationship. Being at a distance from it physically doesn't protect you from the emotional and cognitive impact."

Researcher Caroline Hickman says eco-anxiety is experienced widely across the world

Ms Hickman believes that having an emotional response is good and that people should be concerned about the climate crisis.

"It's healthy to be depressed, to feel grief, rage about this," she says.

However, she says it is important not to get overwhelmed with these feelings.

Dr Bridget Bradley, a lecturer in social anthropology at St Andrews University, is another academic who has has been looking at eco-anxiety.

Her research asks whether this is a new and emerging mental health label and how it can affect family relationships.

Her first small-scale pilot study, in 2021, found it was not just young people who were affected, but also older activists who struggled to get their children or grandchildren to understand.

Her interest in eco-anxiety came partly from her own experience after the birth of her son.

"I was already quite aware of environmental issues and concerns, but having a child just made all of that explode in ways that I wasn't prepared for," she says.

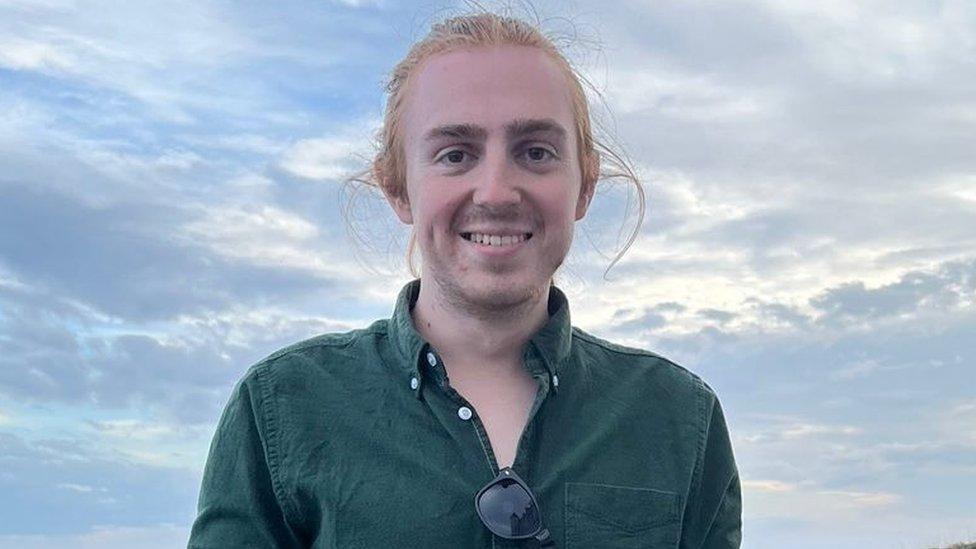

Kyle Downie has removed himself from activism to focus on his mental health

Student Kyle Downie, 22, was an avid climate activist but had to take a break from campaigning due to his mental health. He is now on anti-depressants.

His mental health started to worsen in March last year and while eco-anxiety was not the only cause, he believes it was a factor.

"It wasn't because of eco-anxiety - but I think the eco-anxiety played a big part in being diagnosed with depression," he says.

"I think that's probably the case for a lot of people. Just because that feeling of hopelessness is always there, so it leads to depression."

In 2021, he was heavily involved in COP26 and was a part of The Resilience Project, external, a group who help young people become more resilient to the climate emergency.

He was trained to run an eight-week support programme for other young people around eco-anxiety.

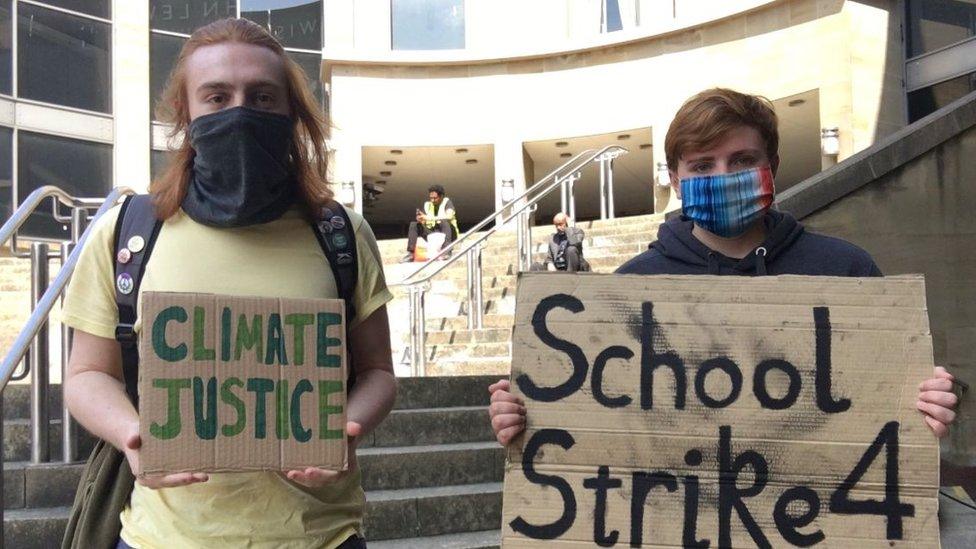

Kyle has also been part of the Fridays for Future protest movement but when he faced burnout, he knew it was time to step away.

Although being surrounded by fellow activists helped him, it wasn't enough to stop him from feeling exhausted.

Kyle has been part of Friday's for Future, where a group of young people take part in climate protests

"When I get burnout, it's usually if I've been throwing myself into activism, not taking enough me time and then it feels very hopeless." he says.

Kyle feels that there isn't any point in continuing his degree, if there is no hope for the future.

He comes from a big family and had previously thought he would want children, but like Jennifer he has now decided he doesn't.

"It's completely changed my thoughts on that from where, I really did want kids, to now I don't because I'd feel too guilty bringing them into a world that is so bleak," he says.

"The future is so bad."

Information and support for issues covered in this article can be found at BBC Action Line.