The radical power of the little black dress

- Published

In 1926, Coco Chanel designed a simple black dress. It was deemed radical at the time, a freeing shape, in a colour previously associated with mourning.

US Vogue went further describing it as "the frock that all the world would wear", the fashion equivalent of Ford's Model T.

Well that's the story anyway. And one of many told in Beyond The Little Black Dress, a new exhibition which opens at the National Museums of Scotland, external this weekend.

"It's a mythic origin story" says Georgina Ripley, principal curator of modern and contemporary design.

"It's about the democratisation, mass production and modernisation of women's dress.

"In actuality, there were plenty of black dresses before that date, including many by Chanel herself, and black was already a fashionable colour but there's something about this moment and the way it embodies the modernising spirit of the 1920s."

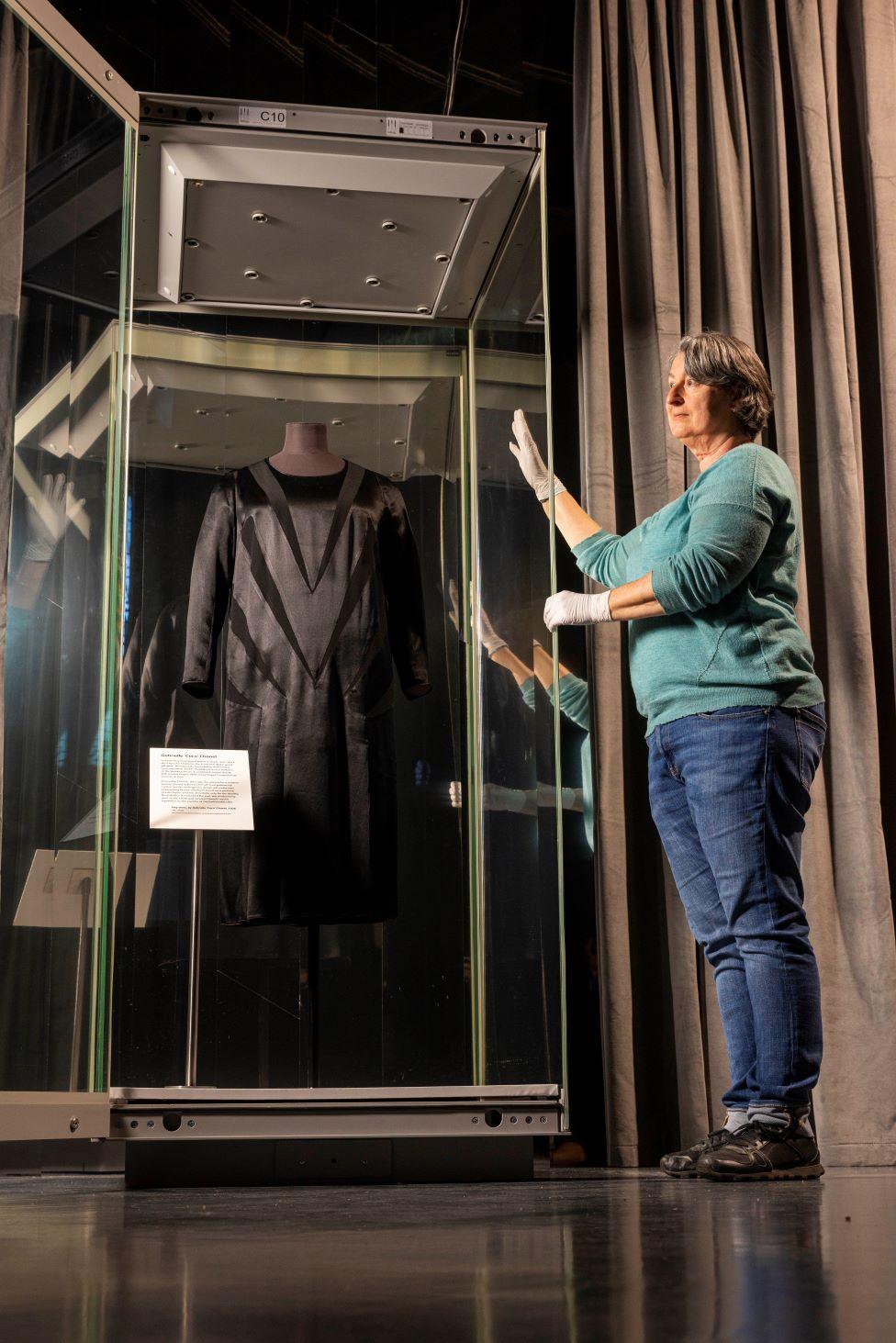

A simple crepe de chine dress made by Chanel in 1926, borrowed from the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin

That moment is how the new show begins the largest fashion exhibition the National Museum of Scotland has ever staged - a simple crepe de chine dress made by Chanel in 1926, borrowed from the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin.

But if Chanel didn't invent the Little Black Dress, who did? In an accompanying book to the exhibition, Little Black Dress: A Radical Fashion, Georgina Ripley suggests it's down to the Royals.

First Queen Victoria, whose mourning garb inspired many fashion followers, and the introduction of synthetic dyes which made it cheaper to produce black fabrics.

"Yet as black became more prominent, there was an important distinction to be made between the rich black of the ruling classes and the 'respectable' black worn by the lower classes," she writes.

Woman's evening dress. French, c. 1929

"As artistic depictions of wealthy Belle Epoque women showed them in fashionable black reception dresses and luxurious evening gowns, the urban working woman was adopting her own simple black dress, in coarse matte fabrics - a style soon to be appropriated by Chanel."

But before then, the death of King Edward VII in 1910, brought a further rush for funeral wear, including that year's "Black Ascot" which inspired many later designers.

The First World War made mourning fashion a sad necessity for thousands of women, and dresses became simpler and more practical to meet demand. Such practicalities are also at play in the Second World War when it's a shortage of material, not fashion, which keeps the hemlines high.

Dress by Fiona Dealey worn by Sade, 1983

Jean Muir Ltd, black suede dress

Black dresses are shown to be simultaneously rebellious and respectful. From a wasp-waisted black silk dress commissioned from Christian Dior by Wallis Simpson, in 1949, to the catwalk show created by Richard Quinn as a homage to the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, which had taken place just two days before.

The show was supposed to open in the summer of 2020, but the delay has allowed the museum to reflect further social changes such as the Black Lives Matter movement, Me Too, and the ongoing climate crisis.

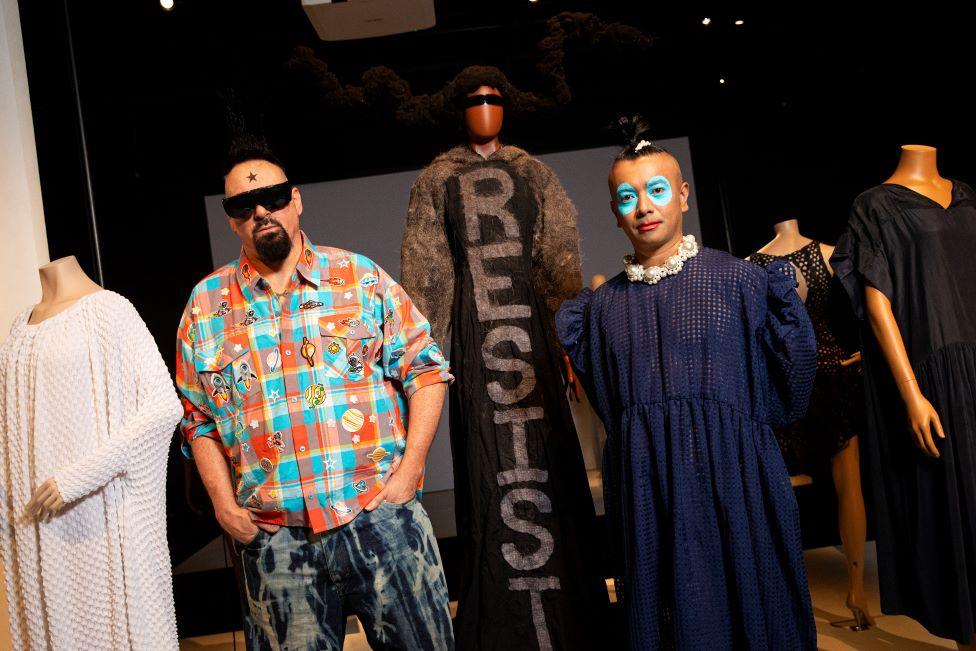

Eco designers Vim and Omi were commissioned to make a dress for the show and chose to reflect all three issues in a striking dress made from nettles, horsehair and linen.

Designers and climate activists VIN OMI with their ‘RESIST’ dress, specially commissioned for Beyond the Little Black Dress.

"We incorporated the street element, the raglan sleeves and the word 'resist' to reflect the politics, and the environment we were working in," says Omi.

"Horsehair used to be used in women's undergarments, but this time, we wanted to use it on the outside so that it was more comfortable, and women are given the liberation of 'look don't touch' so it reflects the Me-Too movement.

"It's about respect, starting a conversation, it's not necessarily wearable."

Vim and Omi have an unlikely supporter in King Charles, who provides much of their material.

"We first met the then Prince Charles about five years ago, when we were looking at large estates and the waste they throw away," says Vim.

"He said to come down to Highgrove and take some of my material.

"Initially we thought well, we'll see, and then he wrote to us the next week and we thought he means it."

The designers spent a year studying the eco system before removing several van loads of nettle trimmings which they used to make a collection, including the dress on display.

They have since used materials from Sandringham and the Castle of May.

"We work with the head gardeners, asking them what they've got," says Vim.

"We don't go along with a shopping list."

"You'll usually find us by the compost heap," says Omi.

"It's a little surreal to think that this September, our latest fashion show will be a collaboration with the King."