'It is almost impossible to run a home and foster'

- Published

Jacqueline McShane has been a foster carer for 10 years

Jacqueline McShane has been a foster carer for 10 years and some of the country's most vulnerable children have passed through her home.

But while the job has not changed, the financial pressures she experiences have.

"We're almost at the stage where it's impossible to run a household and foster," she says. "We're not there yet, but we're almost there."

Like all foster carers, Jacqueline receives an allowance every week to look after children in her care.

Foster carers also receive a fee to cover their own costs. The new allowance plans will not impact those fees.

The rates are set by local authorities and the last time all foster carers in Glasgow, where she lives, received an increase was in 2013, the year Jacqueline began to foster.

"The cost of raising a child has increased significantly in that time," she says.

"I can't go shopping and ask for food prices from 10 years ago."

There are about 3,500 registered foster carers across Scotland

Ms McShane has been campaigning with the IWGB Foster Care Workers Union for an increase in allowances and in the support provided to carers.

"You're constantly putting your own money into it," she says.

"If we didn't have my husband's pension, there is no way we would be able to manage on the money we receive from the council.

"And that's the case for all the foster carers I know. You're spending everything you have to look after these kids."

Ms McShane is one of about 3,500 registered foster carers across Scotland.

The 57-year-old says she has "always loved kids" and wants to "give them good experiences to set them up for life, so they aren't going without".

However, rising energy costs, more expensive social activities and the general cost of living have been crippling to her financial situation, she says.

Ms McShane says she feels she can no longer recommend fostering to other people.

"You love the kids, but you can't manage on the money you get," she says.

"You don't feel valued. The love you get doesn't pay the bills. It just doesn't."

First Minister Humza Yousaf has introduced plans for a minimum recommended allowance for foster carers

This week, as part of his programme for government, First Minister Humza Yousaf has introduced plans for a minimum recommended allowance for foster carers, to be backdated to 1 April 2023.

This brings Scotland in line with the rest of the UK in offering a minimum allowance.

Ms McShane says it does not do nearly enough to make fostering more manageable.

"Even with the new rate, we'll still be worse off in real terms than we were 10 years ago," she says. "That's after a pandemic, after a cost of living crisis."

The Fostering Network, a leading UK charity, has expressed concerns that there is no guarantee the new rates will increase in line with inflation.

Its director Jacqueline Cassidy welcomed the rise.

She said: "We want people to become foster caters. A great many people have fantastic experiences fostering."

But she said the rates do not match those they set out earlier this year as being the amount needed to raise children in care.

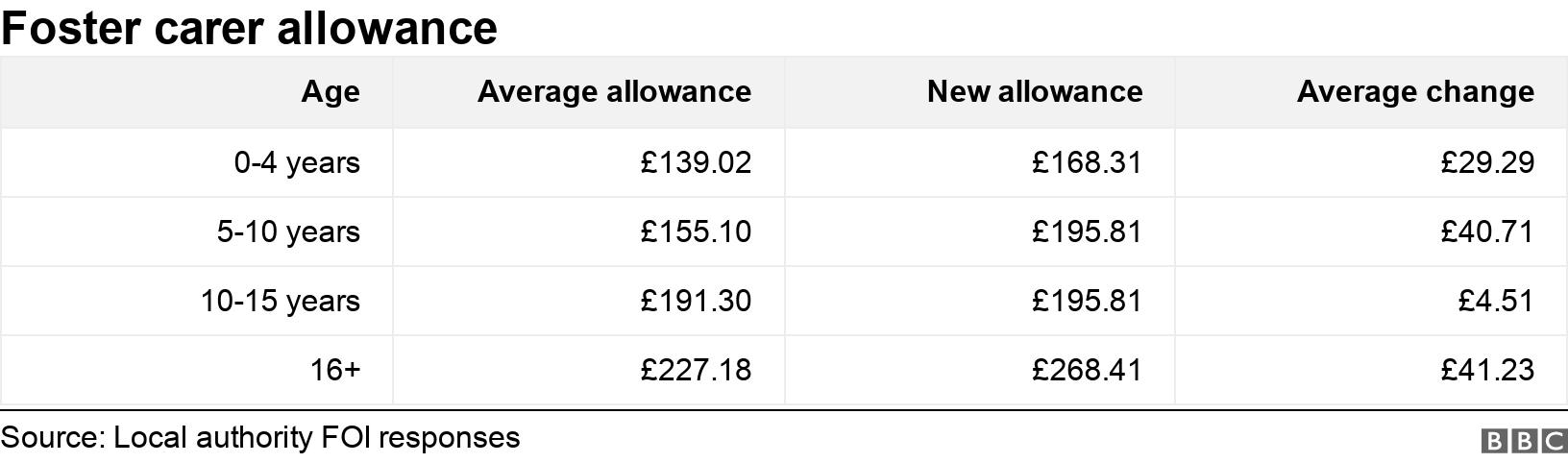

There have also been questions over the decision to merge the 5-10 and 11-15 age groups - previously distinct fee bandings - into one flat rate.

The new allowances will see the younger age group receive, on average, a £41 uplift, while the older age group will receive just a £5 boost.

"That's an enormously hard age group to pay for," Ms McShane says.

"From the clothes they need, to the tech they require for school, I feel that age group is being let down in particular."

Ms McShane says other carers she knows plan to leave fostering when their current placements end, even with this rise in allowances.

The BBC has spoken to several carers off-the-record who have made similar claims.

The IWGB Foster Care Workers Union says the new allowances go nowhere near far enough to save a care system that has been on its knees for years.

In addition to local authority foster care placements, some children are placed with families by independent fostering agencies (IFAs).

In Scotland, as in the rest of the UK, IFAs set their own financial support packages which can be higher than those offered by local authorities.

This is despite all of the money coming from the same local authority budgets.

Ms McShane says she approached an independent agency earlier this year, who offered her £1,000 extra per month for her current placement.

In the end she did not move for fear of disrupting the care of her foster children.

In some cases, carers who have moved from independent providers back into local authority employment have retained increased allowances, creating disparity in how much money foster carers - and the children in their care - receive.

"That's not great, is it," says Ms McShane. "The children you're bringing up, whether they're coming as babies or older children - so much damage has already been done to them.

"They've been taken away from their families through no fault of their own. And yet you're working alongside carers who receive more money for their kids than you do."

Andy Elvin, CEO of independent fostering agency TACT, said the new minimum allowance was a positive move but it does not address the need for fees and allowances of foster carers in Scotland to rise further.

"You're still likely to find that independent agencies are paying foster carers more, and that will have an impact on local authorities ability to recruit and retain foster carers," he said.

In a statement, the Scottish government said the introduction of the new recommended allowance was an important step in their ambition to Keep the Promise to all care-experienced children and young people that they grow up loved, safe and respected.

They said independent fostering agencies set their own allowances and fees, and many worked closely with local authorities.

For Ms McShane, the way fostering is financed is only part of the problem facing the Scottish foster care system. The enormous sacrifices made by foster parents, she feels, isn't recognised, in remuneration or support offered.

She's concerned this will lead to an even greater shortage of foster carers, meaning more vulnerable children will be sent to residential care instead of being placed with families.

"When you become a foster carer the first thing you learn is you are at the bottom of the rung in terms of value," she says.

"It's a fantastic thing to do because of the difference you can make in these children's lives, but you can't do it on thin air."

Related topics

- Published16 May 2023