Making sense of the census

- Published

NRS needed as many completed forms as possible so agencies can use the data to predict demand for services

Census figures are important to deciding where public funds go, from health to school to the Gaelic language but one in 10 did not register in the census figures from March last year, so what could they miss out on?

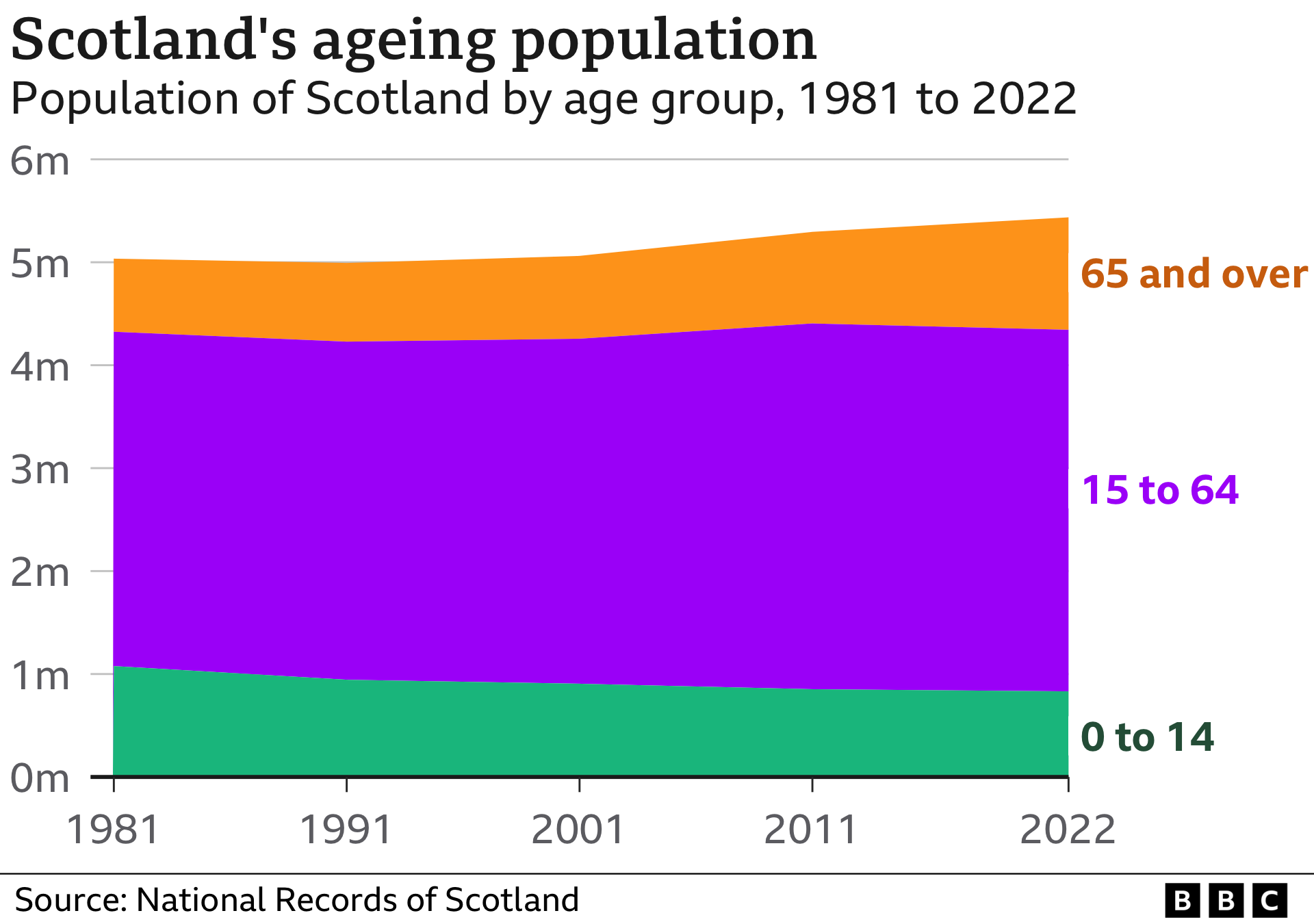

The first release of data is limited. It confirms trends we knew were under way - including the ageing of the population.

It's shifting from the west and south-west, while Lothian council areas grow strongly. That should influence future planning, housing, schooling and social care provision.

We are all held to account every 10 years or so. Counting people goes back to Biblical times. Remember why Joseph and Mary had to go to Bethlehem with the wee donkey?

Pre-Scots were being counted as far back as the 7th century. But it has become a more reliable and important way of finding out about ourselves since 1801.

Back then, with Napoleon to confront, they wanted to find out how many men there were of fighting age. That question doesn't feature now, but instead - how many were in your household on a given night? What about their ages, relationship to each other, ethnicity, faith, sex, gender identity, housing type, transport use, language skills, state of health, place of birth, and so on?

Nearly nine out of 10 Scots households met that legal obligation in March last year, delayed nearly a year by the pandemic and 12 months behind the rest of the UK.

It was a worryingly low response rate. In 2011, 94% responded, and Glasgow was the only council area to fall below 90%.

Though careful statistical massaging is applied, some groups can be disproportionately absent, notably young men. These groups risk losing out as a result. If your demographic doesn't show up in the census data, it may not get the public spending it requires.

Campaigners for the Gaelic language, for instance, look eagerly to these numbers as a gauge of its recovery.

Baby boomers

There are more frequent updates on population from the Registrar General, based on survey evidence. That shows up trends in housing and migration. The national census is supposed to be as comprehensive a snapshot of population as possible, on which those interim updates are then based.

The first release of data is limited, but begins to offer interesting insights, many of them confirmation of trends we could already see.

The trends are clearest over long periods. Among the starker changes in society and population is the illustration that compares the age structure in 2022 with that of 101 years before.

In 1921, there were 2,300 Scots aged 90 and above. Last year, there were 45,000. The male share of that - only 603 Scotsmen in 1921 - has risen to more than a third.

That ageing profile of Scotland is to be expected. The baby boom years from 1945 mean a lot more people are entering the older age brackets. Once they do, they've been getting more likely to live into very old age.

And as they do so, many of them having lost life partners to death or divorce, more people live alone. Single-person households, and not only older people, have been on the rise, and this census release gives us a snapshot of that change. The number of households in total rose by 5.8% - more than twice as fast as growth of the population.

That has implications for planning and for housing. More households, and more with only one person, often being older, means changing demands for different types of housing. Property developers and housing associations will take note.

More very old people with multiple health challenges means more demand on health services and social care. While these people are more likely to live alone, some of that care has to be provided in their homes. Or at least, that's where many prefer it.

And just as we get the census results, one of Scotland's best-known care homes, in Bishopton, Renfrewshire, run by the Erskine charity for military veterans, has announced it is closing and managers are thinking of a pivot to more home-based care.

An insolvency specialist with recent experience of winding up care home businesses warned on Thursday morning that staff shortages and financial pressures on care homes mean we can expect a 10% decline in capacity. We'll get the annual care home census in November but the national ten-year census points to the need to expand capacity.

If you need just one illustration of the importance of a census to provision of public services, turning around the fall in capacity is surely it.

Working age bulge

The shape of the population also shows a reducing share of the population at school age, down 2.5% on 2011. That trend will have implications for spending on education, particularly in the council areas where that trend is clearest. Many rural school rolls are already projected to fall sharply.

And as a larger share is of older and retired people, it is important to watch the share of people of working age. They are the ones paying most of the tax with which to fund education, typically for younger people, and social care, typically for older ones.

Children from Stenhouse Primary School, Edinburgh, holding up cards showing the new estimate of the population of Scotland

In other parts of the UK, the working age population has held up more strongly because of immigration. Scotland has less inward migration, proportionately, so that vital working age bulge is slimming down.

The new census results point to a fall in the number of those aged 15 to 65 by 1.1%, or 37,700.

At the same time, there was a rise from 2011 in the number aged 65 and above by 22.5% or 200,700. In England and Wales, it went up 20%, and by 23.8% in Northern Ireland.

The changes over 10 years may sound small, but they ought to be seen as trends. Since 1971, the share of under-16s has dropped from 25.9% to 15.3% of the total population, while the share of those aged 65 and above has risen from 12.3% to 20.1%. That's a shift in ratio from one in eight to one in five. It is these trajectories that shape planning for future public services, and indicate future pressure on the tax base.

This set of data also gives us a sense of how population is changing within Scotland, and it confirms a shift that's been under way for some decades from greater Glasgow to greater Edinburgh.

In the city of Glasgow itself, the population rose 4.6% in 11 years, There was growth in the more prosperous areas of East Renfrewshire, Renfrewshire and East Dunbartonshire, but other council areas see falling population, including Inverclyde and North Ayrshire.

In the east, Edinburgh's economy has been stronger and its population growing. The consequent price of housing is a well-established challenge the city and those either trying to get on the property ladder or to move in from outside the capital.

To secure a home they can afford, people are choosing to live near the capital - in West Lothian, where growth appears to have slowed, and increasingly choosing East Lothian and - fastest-growing at 16% in only 11 years - Midlothian.

Only Angus goes against the west-to-east trend, with its population down since 2011 by 1.4%.

Transport issues

The cities continue to have the youngest populations, partly reflecting university and college student numbers when the census was taken in March.

In more rural council areas, some are growing in total population. Aberdeenshire is up 4.3% and Highland by 1.4%. Both may reflect economic strengths in the energy sector and tourism.

But Dumfries and Galloway is down 3.6%, and Argyll and Bute by 2.4%. They benefit less than those more northern growing populations in being further from cities, with problematic transport connections.

Island populations are more fragile, with Na h-Eileanan Siar (Western Isles) down 5.5% in a decade, and Shetland also down, due to out-migration.

Those losing population are also finding a high proportion of older people. Argyll and Bute, along with Dumfries and Galloway and Na h-Eileanan Siar have close to 27% of people aged 65 and above, compared with Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen with between 14% and 17%.

Other council areas with falling population also tend to have higher shares of older people, including South Ayrshire and Angus.

Scottish Borders has a small population growth, perhaps because some of the region is within the Edinburgh travel-to-work area, while it also has a high proportion of older people.

These are the findings from the first, very limited release of data from Scotland's census 2022. There is a lot more to come, but we'll have to be patient.

Further releases will start in spring next year, with reports in summer 2024 on ethnicity, the labour market, education and housing.

For the first time, we'll get the full national picture of sexual orientation and trans status. These were not seen as something the government needed to know in 1801.