Judge throws out bid to withhold Nicola Sturgeon inquiry evidence

- Published

The case centres on heavily redacted evidence about whether Nicola Sturgeon misled parliament

Judges have thrown out a bid by the Scottish government to prevent the publication of details about an inquiry into whether Nicola Sturgeon broke the ministerial code.

Ministers insisted they did not hold the information after receiving a freedom of information (FOI) request.

The Court of Session in Edinburgh rejected this argument.

It sided with the Information Commissioner, which said this was a "wholly unrealistic" position.

The government must now reconsider the FOI request, made by a member of the public.

The case relates to an inquiry by the independent advisor on the ministerial code - Irish lawyer James Hamilton.

In 2021, he considered whether former first minister Ms Sturgeon misled MSPs about when she met Alex Salmond's chief of staff in the aftermath of harassment allegations made against Mr Salmond.

Mr Salmond had been cleared of sexual assault charges at a criminal trial.

Mr Hamilton cleared Ms Sturgeon of breaching the ministerial code, but expressed frustration that his report had been heavily redacted.

A member of the public later submitted an FOI to ask the Scottish government to publish all the evidence gathered by Mr Hamilton.

The government rejected the request because it said it did not hold that information, sparking an appeal to the Information Commissioner.

The commissioner found ministers had been wrong to reject the request and ordered them to reconsider the FOI request.

But in a highly unusual move, the government appealed this ruling to the Court of Session.

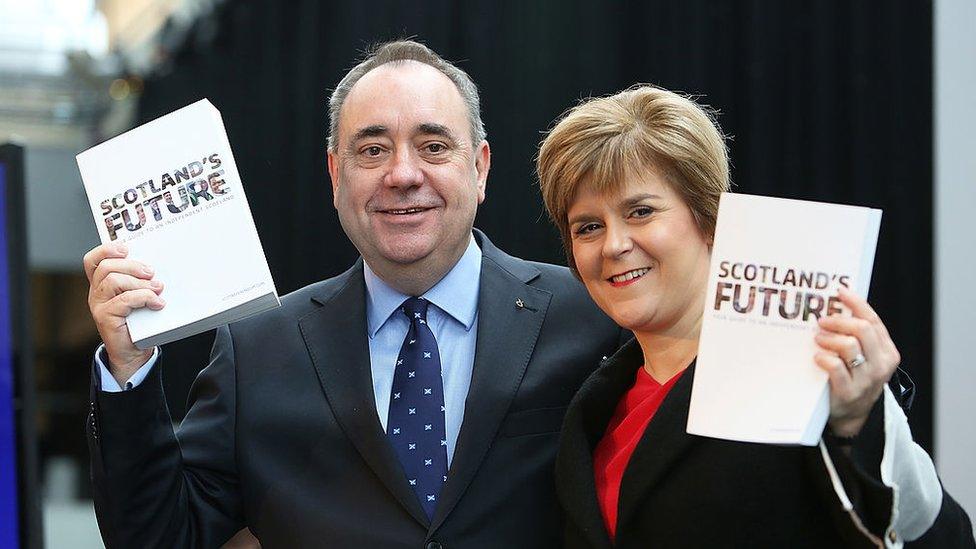

Alex Salmond has recently launched a fresh legal challenge against the Scottish government

James Mure KC, acting for the Scottish ministers, told the court that information gathered for the investigation had been held securely "on behalf" of Mr Hamilton.

He said the lawyer was unpaid and did not have access to the secure IT system which the government secretariat could provide.

The KC said it was only Mr Hamilton's final report which ministers were entitled to see, and that they had no right to access evidence and submissions gathered as it was drawn up.

He said: "The information was for Mr Hamilton to receive, to consider, to control, to store, to use, purely at his discretion."

However, David Johnston KC, acting for the Scottish Information Commissioner, said there was an "appropriate connection" between the ministers and the information gathered by Mr Hamilton.

He said the information had not been left within government systems by chance, or held at arm's length, but was there to form part of an internal process.

'Wholly unrealistic'

He said: "The information which the Scottish ministers claim not to hold is actually information that was only created because of the instructions that were given by the first minister in the first place.

"Mr Hamilton's remit expressly covered gathering the information for the Scottish ministers, which they say they do not hold.

"The ministers' submission is, with respect, wholly unrealistic and has a wholly unworkable meaning of 'hold'."

The judges issued a ruling from the bench, without retiring to consider their verdict.

Judge Lord Carloway said: "We will give reasons for our decision in writing in early course, but in short the court is satisfied the information involved was held by the Scottish ministers in terms of the statute, and we will therefore refuse this appeal."

The case related to a long-running dispute between Mr Salmond, his successor Ms Sturgeon and the Scottish government.

Last month, Mr Salmond launched a fresh legal case alleging misfeasance - the wrongful exercise of lawful authority - by civil servants involved in handling harassment complaints against him.

The dispute began in 2018, when the government investigated two internal complaints of sexual harassment against Salmond.

It admitted in January 2019 that it had acted unlawfully and paid the former first minister's legal fees of more than £500,000 after he launched a judicial review of the case.

Ms Sturgeon then made a statement to MSPs about the row, and set out a series of dates on which she had spoken to Mr Salmond about it.

Lord Carloway threw out the Scottish government's case

Mr Salmond was cleared of sexual assault charges at a criminal trial in 2020. During the evidence, his former chief of staff Geoff Aberdein testified that he had a meeting with Ms Sturgeon and informed her about the complaints "at an earlier point than she had previously admitted to MSPs".

Ms Sturgeon said she had forgotten about this meeting, but referred herself to the independent advisor on the ministerial code - lawyer James Hamilton - to see if she had broken the rules by misleading parliament.

His investigation ran alongside the Holyrood parliamentary inquiry - which became known as the "Salmond inquiry".

Mr Hamilton cleared Ms Sturgeon of breaking the ministerial code in March 2021, describing her omission as a "genuine failure of recollection".

However, the lawyer said he was "deeply frustrated" that his report was heavily redacted when it was published and that he wanted more information to be made public to give context. He warned the redacted report could give an "incomplete and even at times misleading version" of events.

Two weeks later, a member of the public, Benjamin Harrop, submitted an FOI to ask the government to publish all the evidence gathered by Mr Hamilton, ultimately leading to the Court of Session case.

This was a court case which turned on the proper interpretation of the word "held".

It may seem a niche topic, chiefly of interest to lawyers and freedom of information wonks - and, somehow, former Brexit secretary David Davis, who sat in on proceedings in the Court of Session.

But the ruling here could have a significant impact.

To start with there is the specific case - there has long been intrigue about what exactly went on between Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond.

Mr Salmond is keen to bring more information to light, and is currently suing the government in part to "blow apart a cover-up", in the words of his lawyer.

But having lost, the government could potentially find other reasons not to publish these documents. There are other exemptions and court orders they could lean on, should they wish.

Above all of that, there's the principle of ministers taking their own transparency tsar to court.

This row, taken together with the recent refusal to extent the freedom of information regime, risks creating the impression that the government would rather keep certain things under wraps.

- Published23 March 2021