Nicola Sturgeon's reputation on the line at UK Covid inquiry

- Published

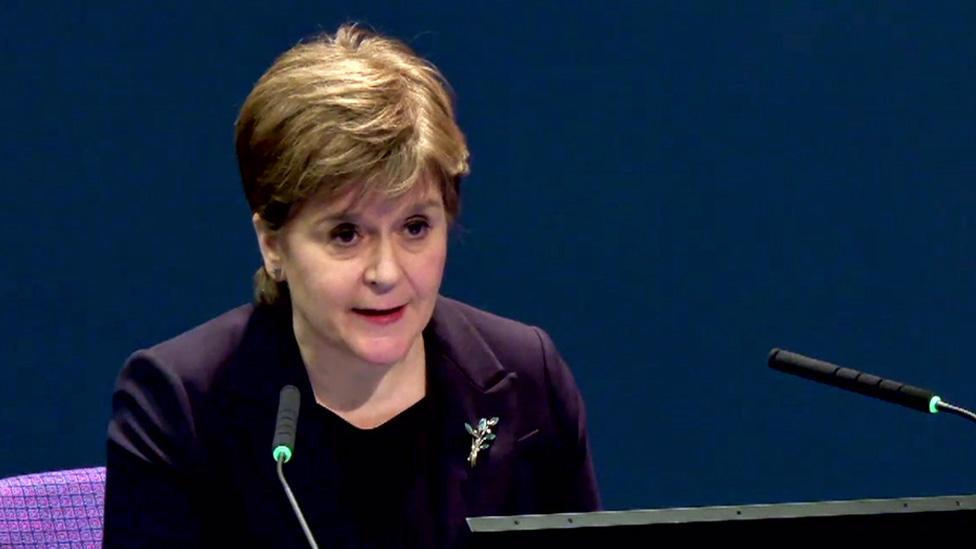

Nicola Sturgeon is giving evidence to the UK Covid inquiry in Edinburgh.

At the height of the pandemic, Scotland's then first minister was a near-constant presence on the nation's TVs and her popularity soared.

At one point, polls suggested an astonishing 100-point gap, external in net satisfaction ratings between the SNP leader and the Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson - a man we now know Ms Sturgeon dismissed privately as a "clown".

But nearly a year after her shock resignation, Ms Sturgeon's reputation is tarnished.

She has faced criticism of her record on education, drug deaths and gender reform - some of it from fellow supporters of independence, who are also frustrated about a lack of progress towards that goal.

In June, Ms Sturgeon was arrested - and later released without charge - in an ongoing police investigation into the finances of the SNP which saw officers pitch a tent on the lawn of her home in the suburbs of Glasgow.

And now her pandemic leadership is coming under close scrutiny.

Ms Sturgeon, seen here with Jason Leitch, gave regular news conferences throughout the pandemic

During the first two weeks of the inquiry sitting in Edinburgh, Ms Sturgeon has been accused of an instinct to hoard power rather than seek help.

It emerged that on Humza Yousaf's first day in the job as Scotland's health secretary in May 2021, National Clinical Director Jason Leitch sent him a WhatsApp message which read: "She actually wants none of us."

Not only did the Scottish cabinet never hold a vote on Covid, according to former deputy first minister John Swinney's evidence on Tuesday, but "in my 16 years in the cabinet, there wasn't a single vote on any single issue because that's not how cabinet did its business".

Giving evidence to the inquiry last week, Mr Yousaf defended his predecessor, saying: "There were times the former first minister needed a tighter cast list and wanted a tighter cast list to make a decision on a specific issue."

Deleting WhatsApps

The second accusation levelled at Ms Sturgeon is one of secrecy.

The inquiry has heard that it was Scottish government policy to delete messages on platforms such as WhatsApp after decisions and salient points had been officially recorded - a process which Prof Leitch once called a "pre-bed ritual".

When he tried to disavow that remark as "flippant," the inquiry chairwoman, Baroness Heather Hallett, remarked that the tone of some WhatsApps did suggest "a rather enthusiastic adoption of the policy of deleting messages".

Ms Sturgeon, the inquiry previously heard, was among those who deleted messages, despite assuring Ciaran Jenkins of Channel 4 News in August 2021, external that she would turn over all relevant communications to the hearings.

Junior counsel to the inquiry Usman Tariq read out a text conversation between Nicola Sturgeon and Liz Lloyd about Boris Johnson

Her former chief of staff Liz Lloyd - who described herself in evidence as Ms Sturgeon's "thought partner" - did provide a tranche of WhatsApps between the two women but was unable to explain why their messages from the first six months of the pandemic were missing.

Questions have also been asked about Mr Yousaf's deletion of messages, and about Ms Sturgeon's use of other forms of communication such as a private email address, direct Twitter messages and, potentially, a personal, rather than a government- or parliament-issued phone.

The inquiry has also heard concerns about a lack of minutes for so-called Gold Command meetings, which involved a handful of key Scottish government ministers rather than the full Cabinet.

Kate Forbes, who was finance secretary at the time, told the inquiry she didn't even know about such meetings in the early stages of the pandemic.

In a statement issued earlier this month, Ms Sturgeon insisted she had not conducted her Covid response through informal messaging platforms and had always acted in line with the policy of her government.

The statement read: "I did my level best to lead Scotland through the pandemic as safely as possible - and shared my thinking with the country on a daily basis.

"I did not get every decision right - far from it - but I was motivated only, and at all times, by the determination to keep people as safe as possible."

Messages show that Ms Sturgeon described former Prime Minister Boris Johnson as a "clown"

The third criticism of Ms Sturgeon relates to competence.

Did the Scottish government make the right preparations for a pandemic, did they respond quickly enough when the virus emerged and did they make the correct calls when the scale of the threat became clear?

These questions lie at the very heart of the inquiry and the Scottish government is far from alone in grappling with them.

Before hearings shifted to Scotland, the inquiry heard claims of toxicity, chaos and dysfunction in Downing Street under a prime minister described by his chief scientific adviser as "weak and indecisive".

Questions about the availability of critical care beds, external and the staff to run them; a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as masks and gowns; and inadequate testing capacity, external in the early stages of the pandemic have been asked in London as well as in Edinburgh.

In Scotland, all three issues were among the failings which contributed to the deaths of hundreds of patients who were discharged to care homes without Covid tests, failings which the former Scottish health secretary Jeane Freeman told the inquiry she would regret "for the rest of my life".

I will regret Covid care home deaths for 'rest of my life' - Freeman

And what of lockdown, announced by Ms Sturgeon for Scotland on 23 March 2020?

"The stringent restrictions on our normal day-to-day lives that I'm about to set out are difficult and they are unprecedented," she told the nation.

Was that the right approach?

Politicians of all stripes insisted they were "following the science" in imposing the most dramatic curbs on individual liberty since World War Two but even some scientists disagreed.

Research suggests there was, in the end, little difference in Covid death rates between the UK nations, despite policy divergence in a number of key areas.

Finally, Ms Sturgeon is accused of "playing politics" when she should have been focusing on public health.

This is an allegation she has always strongly denied.

The specific charge is that she sought divergence with the UK government for political ends - to appear more compassionate, more cautious and, well, more Scottish.

The inquiry heard that Ms Lloyd wrote to Ms Sturgeon in November 2020 expressing the chief of staff's desire to create "a good old-fashioned rammy" with the Tories.

Ms Lloyd's explanation was that she was trying to force the Treasury to provide more funding for necessary public health interventions.

UK government minister Michael Gove denied politicising the pandemic

But the UK government minister Michael Gove told the hearings the comments suggested a "search for political conflict" from a party whose aim was to "destroy the United Kingdom".

He too though was accused of politicising the pandemic.

On 21 July 2020, Mr Gove presented a paper to his colleagues entitled "State of the Union", external which suggested that voters in Scotland believed Ms Sturgeon's government was getting its pandemic response right and Mr Johnson's was getting it wrong.

"There is a real opportunity to outline how being part of the Union has significantly reduced the hardship faced by individuals and businesses across the UK," he wrote.

Two days later the prime minister was in Orkney talking about the "sheer might" of the union with England. Ms Sturgeon responded by saying his visit highlighted the case for the independence.

The inquiry must consider whether any of this constitutional wrangling made any actual difference to the pandemic response.

It is also examining the structures of devolution and whether or not the right powers rest in the right places.

Inquiry counsel Jamie Dawson KC has repeatedly asked whether Scotland would have been better served if the UK government had taken the key decisions about how to respond to the pandemic and the Scottish government had simply implemented them.

A recommendation of that nature from Baroness Hallett, 25 years after devolution was established, would be controversial to say the least.

Whatever she concludes, it appears that both Ms Sturgeon and Mr Johnson retained their respective political philosophies throughout the pandemic which can hardly be regarded as a surprise.

- Published31 January 2024

- Published30 January 2024

- Published29 January 2024

- Published29 January 2024

- Published26 January 2024

- Published25 January 2024

- Published25 January 2024