Lord Provost George Grubb remembers his veteran father

- Published

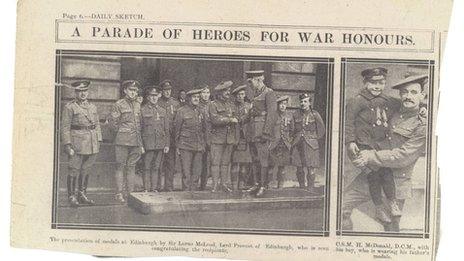

Robert Grubb was honoured at the Presentation of Medals by Lord Provost Sir Lorne McLeod on 22 March 1919

In a moving tribute, Edinburgh Lord Provost George Grubb remembers his father, a Royal Scot awarded the Military Medal in 1917.

Remembrance Day is not just about war and those who died.

It is about those who come back wounded, mentally damaged and unable to live "normal" lives because of the trauma of battle.

We remember the fallen and the wounded during 10 years in Afghanistan.

I have in my possession a photograph of my dad standing in the archway of Edinburgh City Chambers, along with others, as they received their World War I medals from the Lord Provost, Sir Lorne MacLeod.

My dad was awarded the Military Medal in 1917, but by the time he received it in 1919 he was an amputee at age 21.

His artificial limb was a heavy one. He strapped it on every morning.

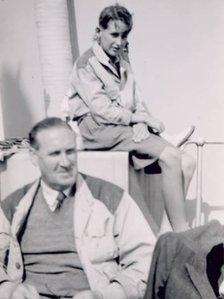

Robert (L) and George Grubb on a boat in the Clyde in 1947

It was a full limb, with little flexibility in it, so he walked by swinging the whole limb in front of him.

He kept a spare under the bed, and my brother and I used to hide beside it when we played hide and seek.

One Saturday during the war years we took a walk up the Radical Road in Holyrood Park.

We started at the palace end, and walked up the steep path and down to the road and then up to Salisbury to get a Marchmont Circle tram home.

It was a great walk. When we got home my mother remonstrated with my Dad.

"Why did you go up that path? You know how steep it is and you will suffer for it tomorrow," she said.

Later I discovered his "stump" - the small remaining bit of the leg that his artificial leg was attached to - was chaffed and bleeding. In later years I took my own children up the Radical Road.

We were all fit and able and I began to realise what it cost my dad in his everyday life.

He also took me to Edinburgh Castle to see the shrine. I think he wanted me to know about service, discipline, devotion and sacrifice.

Sgt Robert Grubb (R) of the Royal Scots with his colleague Sgt JH Dodds in April 1916

He didn't talk or lecture, he just let me take it in, and it was awesome.

Once again, on reflection, I realised that when he looked at the memorial books he was looking at the names of his friends who didn't come back.

He died two months before he was due to retire from the civil service.

He had been looking forward to retirement and had planned holidays.

After his funeral I took his limbs back to the Ministry of Pensions.

They were wrapped up in a rucksack, the one I used in National Service.

I waited on a bus. When it came I put them in the luggage space and then carried them into the Pensions Office.

"Put them over there - do you want a receipt?" I was asked.

"No thank you," I said. "I'm just returning them to the government who sent him to the trenches."

Many memories still live on but every time I walk through the arches of the City Chambers, often past demonstrators, I think of my dad standing there receiving his medal for bravery from the Lord Provost, and that he lived in the trenches, the medical treatment he received when he was shot up, and the life that he lived until his death.

He was my hero.