Meeting the Boson Man: Professor Peter Higgs

- Published

Professor Peter Higgs, who proposed the existence of the Higgs boson has been awarded the 2011 Edinburgh Award for his impact on the city.

The Higgs boson: made in Scotland.

Well, not quite. But Scotland has a good claim to be the birthplace of the idea.

First, here's the problem: take an object - say Isaac Newton's apocryphal apple. Here on Earth, it weighs something. But even if you put the apple in the weightlessness of space it will still have mass. Why? Where does mass come from?

Newton couldn't explain that. Neither could Einstein. But in 1964 Peter Higgs did.

In fact 1964 was something of an annus mirabilis in theoretical physics. No fewer than three papers were published, each taking a different approach to explaining how mass could happen.

All three papers are regarded as underpinning current theories about fundamental particles, cited roughly equally by subsequent generations of physicists.

Two of them were authored by teams of researchers. Peter Higgs, then a lecturer at Edinburgh University, published alone.

And it's his concept of a particle which endows other fundamental particles with mass, and which now bears his name, which has captured the public imagination.

So it's not too surprising that in the ensuing half century he's had to suffer more than his fair share of public misconceptions.

He says there was no "eureka moment", thus killing the story that the concept came to him while out walking in the Cairngorms.

Indeed he's modest about his role.

"This is something I've lived with for a very long time now," he told me.

"It's now nearly 48 years since I did this work in 1964.

"It was another 12 years before (Professor) John Ellis of CERN suggested it was time experimentalists take an interest in what I'd actually pointed out in an added paragraph to a paper which had, in its first version, been rejected."

Public eye

Professor Higgs has something of a reputation for being a recluse. It's undeserved. In person he's affable and approachable.

He lives quietly in Edinburgh's New Town but can often be spotted in the capital's concert halls and museums. He's in his eighties now, a grandfather, and retired from his role as Professor Emeritus at Edinburgh University.

As such it's not unreasonable if he chooses to spend most of his time out of the public eye.

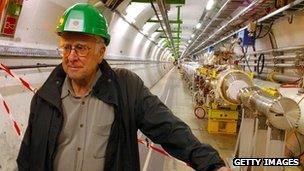

Professor Peter Higgs inside the Large Hadron Collider tunnel at CERN, Geneva

A colleague screens his emails, of which there are plenty. Some come from present day theoretical physicists, others from non-scientists with - to put it diplomatically - unconventional theories on life, the Universe and everything.

Also to be filtered: dozens of interview requests from the world's media. He accepts only a few because it would be impossible to accept them all.

I could claim he gave me an interview thanks to my dogged journalistic technique but I'd be lying. In reality I asked politely and waited. I was assured that a reply - yes or no - would come in time and sure enough, a few months later, it did.

Why did he say yes? Again, any claim of special skills on my part would be untrue. It's more likely to be a result of the long and distinguished track record of colleagues across the BBC in covering science. The fact that Professor Higgs's father was a BBC audio engineer probably didn't hurt either.

There's only one telephone in Peter Higgs's flat. No Internet. No mobile phone. He's no Luddite, but it's worth remembering he did his most celebrated work in a different technological age.

In 1964 he didn't have a pocket calculator, let alone a desktop computer. He came up with his theory using nothing grander than a fountain pen.

Scientific proof

He's only visited the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) once: back in 2008, the year it was first switched on. But he can be expected to make another visit this year. Hopes are high that we will know within months whether the Higgs particle exists. If and when an announcement is to be made he will be top of the guest list.

Has he ever doubted that the Higgs particle would be found? He smiles:

"I suppose I should be technical and say I'm about three standard deviations confident.

"But I want five standard deviations just as the experimentalists at CERN do."

The next proton run of the LHC will start within weeks. Its beams will be more powerful than ever before. Its research teams, drawn from across Europe and beyond, are confident they know what a Higgs event will look like.

Until then the Higgs Boson is still only a theory. But that could change very soon indeed, and with it our understanding of the Universe.

- Published20 December 2011

- Published19 December 2011

- Published4 July 2012

- Published13 December 2011

- Published24 July 2011