Filming in court 'not precedent'

- Published

The decision to allow the sentencing of David Gilroy at the High Court in Edinburgh to be filmed and shown on TV news programmes does not mean courts will be opened to cameras more often, a spokeswoman has said.

Cameras have been allowed in Scotland's courts since 1992 but only if all parties involved have given their consent.

The guidelines ask judges to consider "whether the presence of television cameras would be without risk to the administration of justice".

In practice this has meant the presence of cameras has been very rare - restricted to a few high-profile appeal court cases.

Cameras have previously been allowed in court to film footage for documentaries which are broadcast at a much later date and are heavily vetted by legal representatives.

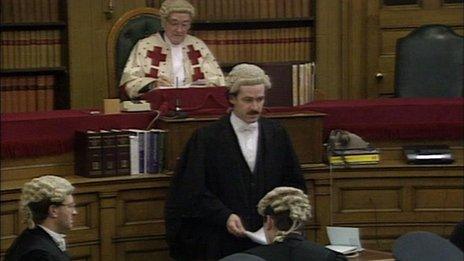

In a rare case, Lord Ross allowed news cameras into the High Court in Edinburgh in 1996

However, there was one unusual case in 1996 when judge Lord Ross allowed a BBC Scotland news programme into the High Court for the sentencing of two armed robbers.

The senior judge had branded the sentencing system in Scottish courts a "charade" because prisoners did not serve the full term and he invited in the cameras to witness his judgment.

More proscriptive

On that occasion, the whole court, including the two accused, was filmed.

The filming of the sentencing of David Gilroy for the murder of missing Edinburgh office worker Suzanne Pilley was much more proscriptive.

Scotland's top judge, the Lord President and Lord Justice General, Lord Hamilton granted permission for the sentencing to be filmed.

However during the sentencing of Gilroy on Wednesday, the camera focussed on judge Lord Bracadale.

Nobody else featured in the footage except the macer and the clerk.

David Gilroy was not filmed by the camera recording the sentencing

Gilroy was not filmed and the footage was vetted by the courts service before STV, which recorded the sentencing, distributed it to other outlets.

Elizabeth Cutting, the head of judicial communications for the Scottish Court Service, said judges had become more familiar and comfortable with cameras in court after recent appeal cases were recorded.

But she said each case would be assessed on its merits and there could be no risk to the administration of justice.

Too high

Ms Cutting told BBC Scotland that there was still a huge amount of judicial discussion around the issue.

She said: "A judge is in charge of managing a trial. Anything which they think could jeopardise the administration of justice cannot be allowed.

"We cannot have a situation where there is a high risk of jurors not wanting to serve on juries or witnesses not wanting to give evidence because they are being filmed."

Of the Gilroy sentencing, Ms Cutting added: "This does not signal an opening up of the courts for cameras to be allowed a lot more frequently.

"Every application will be looked at individually and if a judge feels the risk is too high they will not allow it."

She said that it was less of a risk to allow filming at appeals or sentencing than it would be during a trial.

Filming in English courts has been banned since 1925.

It is believed the UK government is to bring forward legislation in the Queen's Speech which would allow the televised sentencing of offenders in English and Welsh courts.

It is part of plans to improve transparency in public services.

Filming would only take place of the sentencing, not the trials themselves or the verdicts delivered by the jury.

Suzanne Pilley: The Woman Who Vanished will be shown on BBC One Scotland on Wednesday 18 April at 22:45.

- Published18 April 2012

- Published18 April 2012

- Published18 April 2012