Hidden Doggerland underworld uncovered in North Sea

- Published

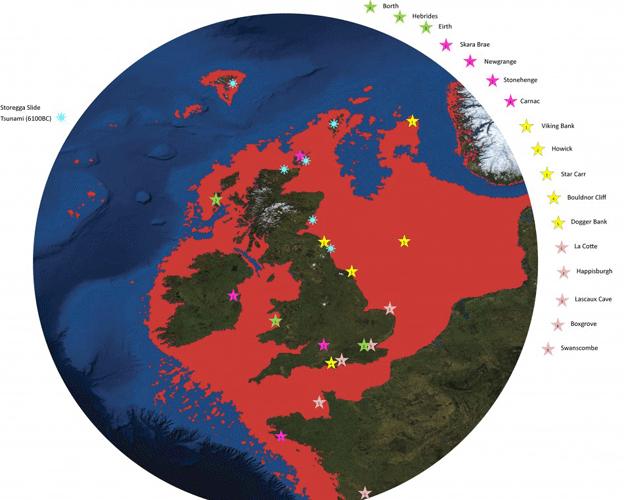

A map of the UK with Doggerland marked as red

A huge area of land which was swallowed up into the North Sea thousands of years ago has been recreated and put on display by scientists.

Doggerland was an area between Northern Scotland, Denmark and the Channel Islands.

It was believed to have been home to tens of thousands of people before it disappeared underwater.

Now its history has been pieced together by artefacts recovered from the seabed and displayed in London.

The 15-year-project has involved St Andrews, Dundee and Aberdeen universities.

The fossilised remains of a mammoth uncovered from the area

The results are on display at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition in London until 8 July.

The story behind Doggerland, a land that was slowly submerged by water between 18,000 BC and 5,500 BC, has been organised by Dr Richard Bates at St Andrews University.

Dr Bates, a geophysicist, said "Doggerland was the real heartland of Europe until sea levels rose to give us the UK coastline of today.

"We have speculated for years on the lost land's existence from bones dredged by fishermen all over the North Sea, but it's only since working with oil companies in the last few years that we have been able to re-create what this lost land looked like.

"When the data was first being processed, I thought it unlikely to give us any useful information, however as more area was covered it revealed a vast and complex landscape.

"We have now been able to model its flora and fauna, build up a picture of the ancient people that lived there and begin to understand some of the dramatic events that subsequently changed the land, including the sea rising and a devastating tsunami."

Dr Richard Bates at work building up a picture of the ancient landmass

Ancient tree stumps, flint used by humans and the fossilised remains of a mammoth helped form a picture of how the landscape may have looked.

Researchers also used geophysical modelling of data from oil and gas companies.

Findings suggest a picture of a land with hills and valleys, large swamps and lakes with major rivers dissecting a convoluted coastline.

As the sea rose the hills would have become an isolated archipelago of low islands.

By examining the fossil record (such as pollen grains, microfauna and macrofauna) the researchers could tell what kind of vegetation grew in Doggerland and what animals roamed there.

Using this information, they were able to build up a model of the "carrying capacity" of the land and work out roughly how many humans could have lived there.

The research team is currently investigating more evidence of human behaviour, including possible human burial sites, intriguing standing stones and a mass mammoth grave.