Scotland's forgotten link with WW1 polar bear Baśka

- Published

Polar bear Baśka Murmańska with Polish soldiers

Research by BBC Scotland has uncovered the forgotten story of a polar bear who caused a sensation when she marched in step through Edinburgh alongside hundreds of Polish soldiers in the autumn of 1919.

The bear, called Baśka Murmańska, was said to have stood to attention at appropriate moments, making the military salute with her paw.

Baśka was the mascot of a Polish battalion that had been fighting the Bolsheviks in Northern Russia and had been evacuated to Scotland.

This military parade through Edinburgh passed the spot in Princes Street Gardens where a statue stands today of Wojtek, a similarly charismatic, brown bear, who also ended up in the Scottish capital after his adventures with the Polish army in exile during World War Two.

Wojtek, famous for his love of beer and cigarettes, was bought as a cub in Persia in 1942 by Polish troops after they had been released from prison camps in the Soviet Union.

But remarkably, he was the second of two Polish bears, one brown, one white, that travelled to Scotland.

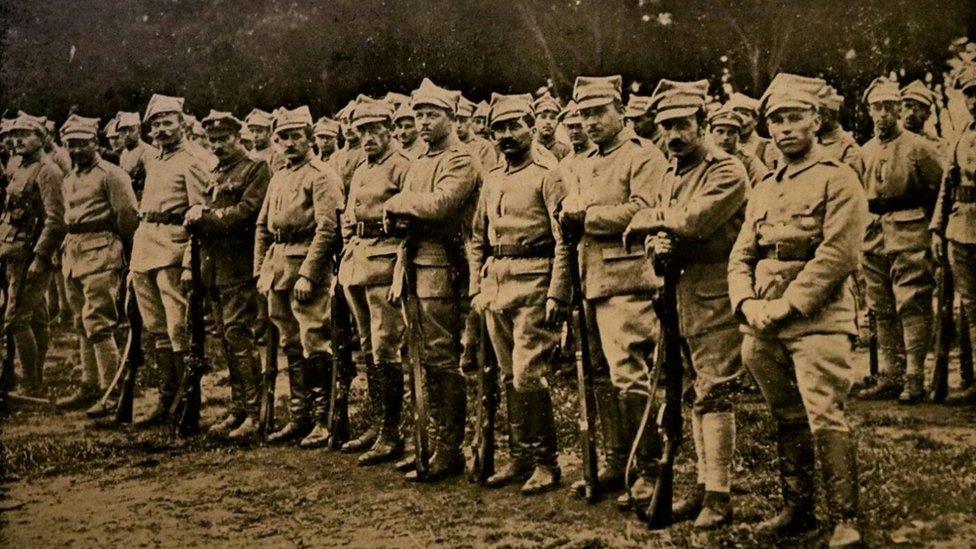

Wojtek was a brown bear that came to Scotland at the end of World War Two

Twenty-three years before Wojtek's story began, a newly-formed battalion of exiled Poles also crossed paths with a young polar bear in the Siberian city of Archangel amid the chaos of the Russian civil war.

During World War One Poland was a stateless nation and Polish soldiers had served in both the Imperial Russian Army and on the other side with Germans and Austrians.

When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917 and Russia dropped out of the war, independent Polish units were formed only to find themselves embroiled in a vicious civil war.

In the far north of Russia several hundred Poles joined up with White Russian forces and a multi-national anti-Bolshevik coalition which included British, French, Italian, Serbian, American, Canadian and Australian soldiers.

They had to cope with sub-zero temperatures and frostbite in the long Russian winter, while in summer the thaw turned much of the tundra into a vast swamp swarming with mosquitoes.

'Lady's favour'

The fighting was brutal and an atmosphere of suspicion prevailed.

Concern about espionage was ever present with suspected spies being thrown into holes cut in the ice of the White Sea.

While on leave from the strains of the frontline the Polish troops spent a few weeks in Archangel, which was in a state of chaos and full of refugees, and it was here they acquired their mascot.

Sebastian Sosiński from the Polish town of Nowy Dwór, has studied the story of Baśka.

"The Murmańczycy (the Polish Murmansk legion), got their polar bear because of a woman," he says.

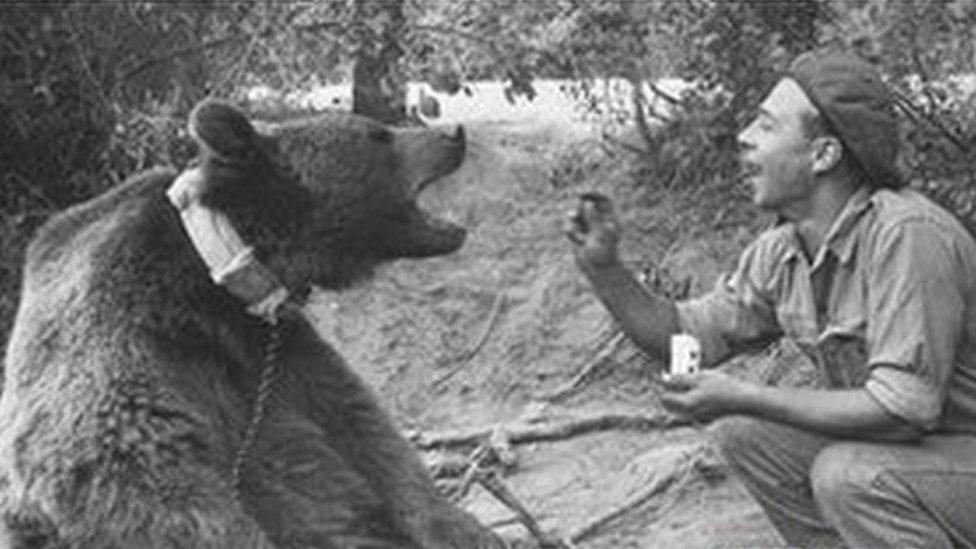

A painting of Baśka and Polish military leader Marshal Józef Piłsudski

"One of the Polish soldiers was competing with an Italian officer for a certain lady's favour. She liked animals very much. The Italian had a pet arctic fox with white-blue fur. But the Pole out-classed the officer by going to meet her with a polar bear he bought at the Arkhangelsk market."

It seems this gesture failed to spark a romance but it did begin the remarkable love affair between the Polish army and bears - which was to be repeated in World War Two.

Although not fully grown, Baśka was a wild animal and at first was prone to snapping at her captors. She also apparently created problems for the Poles by killing a dog that belonged to a senior British officer.

However, back at the frontline one soldier, Cpl Smorgonski, managed to tame her and Baśka was soon so domesticated she slept curled up at the foot of his bed.

According to Mr Sosiński, the soldiers "were crazy about their polar bear".

"She was made an official member of the army, and given the military rank of 'Daughter of the regiment'. She even got her own military rations like any other soldier," he says.

'Ferocious temperaments'

Aileen Orr has written a book about Wojtek the Polish soldier bear from World War Two, a story that is also being made into a film. She says there are incredible similarities between the two bears.

She says: "Wojtek, like her, had been taken very young and had been completely humanised. They hadn't actually been exposed to other bears so they took on all the attributes of being not just men but also being soldiers. And Wojtek did the same thing.

"It's strange times in warfare. When soldiers are deprived of family and living a normal life, a big animal like this becomes everything that they have lost in many ways. I can understand exactly how proud they were of having her.

"Polar bears have ferocious temperaments and it is quite an achievement to tame one. They could trust her and she could trust them and I notice that they did play a lot and have some fun with their bear too, so hats off to them.

"Had they been cruel to her she certainly would have killed them in an instant."

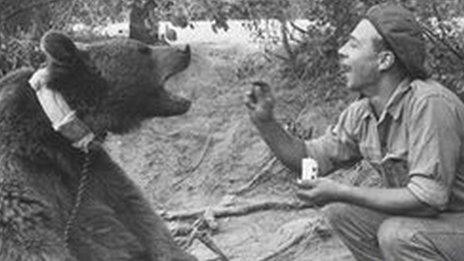

Baśka is thought to have been well looked after by soldiers

At this stage Baśka and the Polish Murmansk battalion were stationed on the frontline at Onega along the route of the recently built Murmansk-Archangel railway line. Some of the troops served as guards on armoured trains.

However, the Allied war effort was not going well. The Bolsheviks were advancing and mutinies had become common in the White Russian armies.

The Poles helped quell one such rebellion capturing and tying up many of the Russian mutineers until they were taken away by British troops.

'Extremely weary'

Back in Britain the undeclared war in Northern Russia was highly unpopular among certain sections of the public and had never been seen as a priority by Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

Bizarrely, many of the British soldiers serving in the tough conditions of Northern Russia had initially been sent there because they weren't considered fit enough to fight on the Western Front.

Dr David Worthington, the head of the centre for History at the University of the Highlands and Islands, believes the struggle against the Bolsheviks was unsuccessful, in part, because of divisions among the allies and general war weariness.

He says: "They were so diverse in the motivations and interests it was hard to unite them against the enemy.

"You had soldiers from various countries in Europe, they found it hard to rally round a particular factor in why they were there, and what they were doing and what they were seeking to achieve. I think a lot of soldiers in fact were extremely weary, extremely keen, desperate probably to get home and focus on other things."

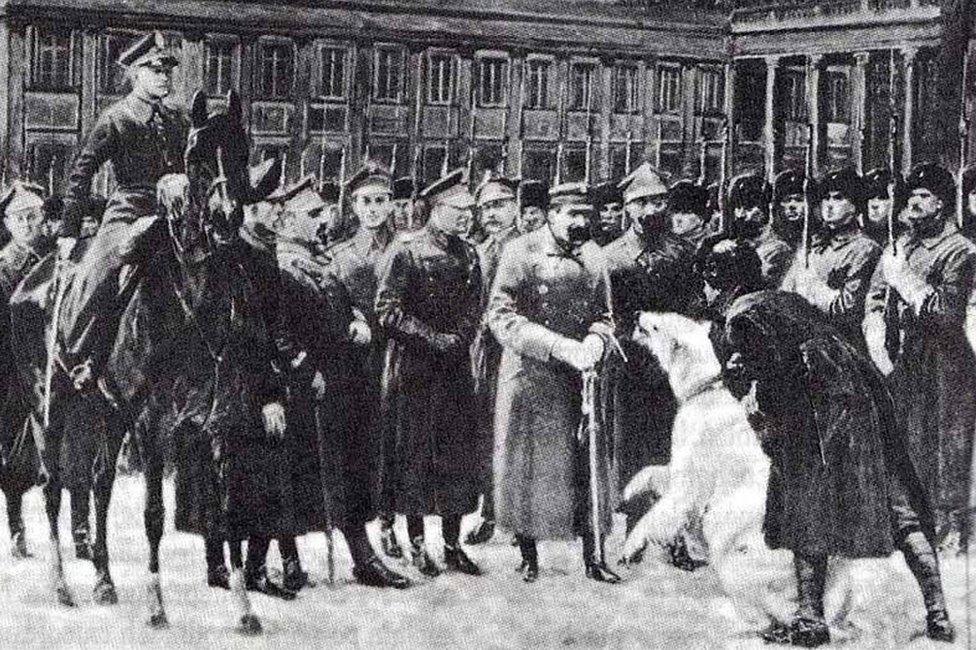

Polish soldiers at Dreghorn in Edinburgh

By the summer of 1919 the British and other allied powers had decided to withdraw before another winter took hold.

The evacuation was a complex logistical operation with six and a half thousand refugees joining the soldiers of the expeditionary force on boats sailing for Britain.

One of these ships was the Toloa, which arrived in Leith on 27 September carrying the 460 men of the Polish legion and also their polar bear.

Marching through Edinburgh to and from the "comparative comforts" of their accommodation at Dreghorn Barracks in their distinctive blue uniforms they "attracted a large amount of attention" according to contemporary reports in The Scotsman newspaper.

'Greatest sensation'

The newspaper also noted that "a large proportion of them are youths, engaging in manner and well educated" and that "most of the members of the legion have had strange and exciting experiences".

It was Baśka though who became the centre of attention as writer and diplomat Jan Meysztowicz recalled in an edition of Voice of Poland magazine published years later in August 1943.

He wrote: "A certain Sunday, in November 1919, the passers-by in Edinburgh were astounded at the unusual sight of a battalion of obviously foreign infantry parading in Princes Street. Their equipment revealed they were coming from the far north.

"But the greatest sensation was aroused by an enormous white polar bear, trained to keep pace with the ranks, and even standing to attention at appropriate moments, making the military salute with his paw."

Amazingly, this march went right passed the spot where a statue now stands of the World War Two soldier bear Wojtek.

The statue of Wojtek in Edinburgh

Ms Orr, who was instrumental in getting the monument erected in Princes Street Gardens, says she was astonished to learn of about the visit of Baśka in 1919.

"I had heard a very vague story of another bear coming to Scotland with the Poles very early on around about the early 1900s. I didn't actually know it was during war time," she says.

"But it seems quite remarkable that she also had been made a soldier and had walked passed the spot where Wojtek now stands. The story of Wojtek has been full of extraordinary and strange coincidences and this is yet another."

The Poles and Baśka appear to have spent over two months in Scotland before setting sail in early December from Leith to newly independent Poland.

On their return they were greeted as war heroes at a parade in Warsaw where Baśka was again the star attraction. Standing on her hind legs she is said to have saluted the Polish military leader Marshal Józef Piłsudski and offered her paw to shake his hand.

Mysteriously disappeared

With her new-found celebrity status Baśka Murmańska accompanied her unit to their barracks at the Modlin Fortress, 20 miles from the Polish capital, but she had only been there for a short time when tragedy struck.

During the summer of 1920 the polar bear was suffering from the heat and the soldiers would take her down to the river Vistula to cool off.

However, one day she went Awol and swam off downstream.

Later, seeking food and with no fear of man, she approached some peasants working near the river. Perhaps misunderstanding the bear's intentions they attacked and killed her.

Baśka's soldier comrades, who had been frantically trying to find her, were said to be distraught when they learned of her death.

Her body was taken to taxidermists and she was later put on display in a museum in Warsaw but her remains mysteriously disappeared after World War Two.

Baśka is still remembered in Poland but until now the link with Scotland had been forgotten.

Statue of Baśka at Modlin Fortress in Poland where her story has not been forgotten

Mr Sosiński is the president of the local tourism organisation at the Modlin Fortress and has set up a Baśka Murmańska heritage trail there. He was delighted to hear about the Scottish connection and hopes it will help to build new ties between the countries.

He says: "I see a great chance for cooperation between Edinburgh and Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki, where Modlin Fortress lies.

"In the tourism context, as there are now flights connecting the two locations, but also in the promotion of Baśka's story.

"I don't want her to be forgotten."

He adds: "It's unbelievable that a polar bear, one of the most dangerous animals in the world, marched through the streets of Warsaw and Edinburgh and made such a mark in history.

"We still don't know her full story but, if this polar bear spent so long in Scotland maybe there are new pictures or other traces from that time."

'Quite remarkable'

Dr Worthington is running a short course later this year on the historical links between Scotland and Poland.

He believes the story of Baśka can help dispel one misunderstanding about Scottish Polish relations.

"We know that lots of Scots migrated to Poland," he says.

"This peaked in the 16th and early 17th century. Then Poland is carved out of existence it ceases to exist as a state at the end of the 18th century, and I think people think that is the end of Scottish Polish relations until the Second World War when Polish soldiers come in tens of thousands to Scotland.

"We know all about the incredible contribution they made. But actually, there is all sorts of interesting stuff going on between these two times, from 1795 to 1940, and this is just one of those incidents.

"Of course animals were used in times of warfare repeatedly but it is extraordinary, perhaps especially extraordinary in retrospect given what we know about Wojtek, that there is a precursor, a female polar bear from the far north, who again represents the Poles, who comes to Scotland.

"It is quite remarkable."

- Published23 January 2017