Edinburgh scientists discover mammoth secret in ivory DNA

- Published

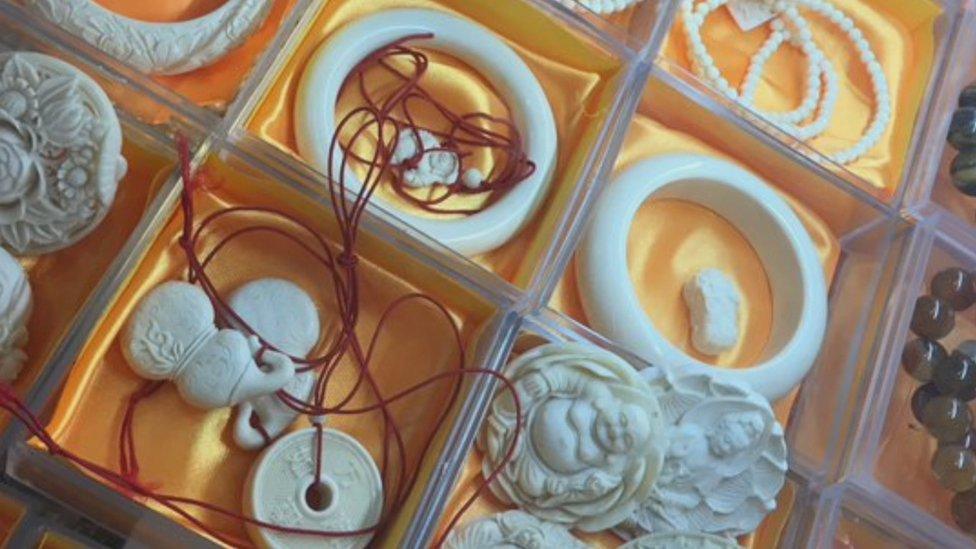

Woolly mammoth DNA has been found in trinkets branded as elephant ivory

Scientists based at Edinburgh Zoo are cooperating to create a genetics laboratory in Cambodia to fight the illegal ivory trade.

While trying to save elephants, they have found ivory from another animal that is now extinct.

In the WildGenes laboratory of the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, Dr Alex Ball is drilling what sounds like a giant tooth.

Which is in effect what it is: an ornately carved elephant tusk.

The lab is working with three partners in a project funded by the UK government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Together they are building Cambodia's scientific capacity to preserve its wildlife and combat the ivory trade which passes through it.

Dr Alex Ball drills the elephant tusk to analyse its dentine and calcium

Dr Ball's team has helped establish the first conservation genetics laboratory in Cambodia.

The country lies on an important route for smuggling ivory from Africa and Asia. Which continent the tusks have been stolen from can have legal implications.

"Elephants are being decimated in their thousands across Africa," Dr Ball says.

"One of the key things about Cambodia is that we have hardly any information about the ivory trade."

There are approximately 500 elephants hidden in the jungles of Cambodia

DNA from tusks is unlocking those secrets.

"We can basically break down that dentine and calcium and get those cells out the ivory - and then identify the individual that grew that tusk," he added.

The WildGenes laboratory is the only zoo-based animal genetics lab in the UK and one of only a handful in Europe.

The head of conservation and science at the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, Dr Helen Senn, says it plays an important role.

Dr Helen Senn is part of the team working at WildGenes laboratory

She continued: "Often endangered species are quite genetically unusual and unique and they haven't been worked on before.

"They're not interesting to medicine or agricultural science.

"So we have to develop novel methods to - for example - study pygmy hippos or scimitar-horned oryx."

But in the work on Cambodian ivory samples the researchers have uncovered something even more exotic: DNA from woolly mammoths.

Cambodia customs officials seized a record-breaking haul of Africa ivory this month

Mammoths are not covered by international agreements on endangered species for the unfortunate but unavoidable reason that they have already been extinct for around 10,000 years.

It is relatively easy to spot the difference between elephant and mammoth tusks.

But once the ivory has been carved into trinkets it is far harder.

Ivory trinkets are among the items sold in the illegal trade

"To our surprise, within a tropical country like Cambodia, we found mammoth samples within the ivory trinkets that are being sold," says Dr Ball.

"So this has basically come from the Arctic tundra, dug out the ground.

"And the shop owners are calling it elephant ivory but we've found out it's actually mammoth."

Cambodia has between 250 and 500 wild Asian elephants of its own. It is difficult to assess how well or otherwise they are is faring - or even how big the population is - as they tend to stay deep within the jungle.

DNA sampling can provide an insight here too, although drilling tusks is not an option on live elephants.

Instead the conservationists have to seek out faecal samples - DNA from elephant dung identifies individual elephants and so builds a picture of the total population.

African elephants are classed as vulnerable, the Asian species is endangered.

The trade in their ivory goes hand in hand with smuggling other illegal products like rhino horn and pangolin scales.

That is why the partners are developing more genetic tools to help Cambodia identify other kinds of contraband before it is too late.

- Published3 October 2016

- Published26 August 2018

- Published16 December 2018