Artist explores the 'dirty secrets' of Scotland's colonial past

- Published

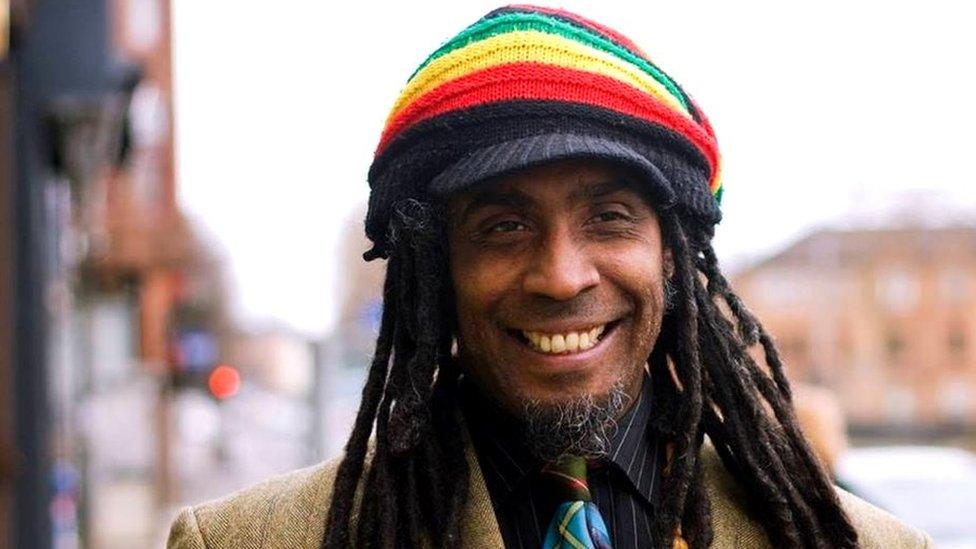

Alberta Whittle was born in Barbados and has lived in Scotland all her adult life. In a new exhibition at Edinburgh Printmakers she uses artwork to tell the story of the country's colonial links.

Alberta Whittle says: "Scotland has been sitting in a place of colonial amnesia. Scottish cities are built on the bodies of black and brown people"

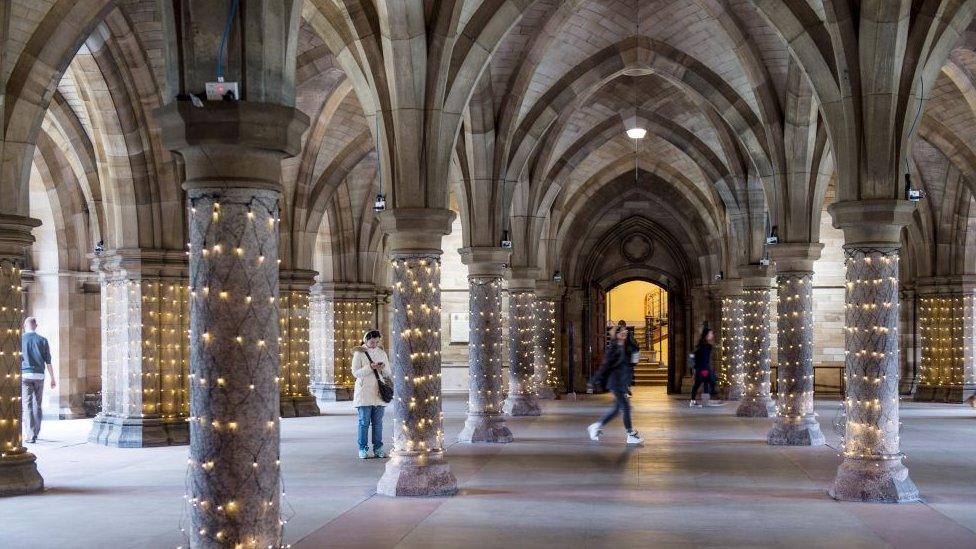

The former North British Rubber Company in Scotland's capital is the venue for the "Transparency" exhibition.

Whittle views the building as a "testimony" to colonialism because it manufactured rubber products from raw materials sourced from the British empire.

She explains that Scotland's wealth was "made possible" through an "active participation with slavery in the Caribbean, the Americas and in Africa".

The artist goes on to say: "Scotland's relationship to Empire and colonialism is a dirty secret. A long overdue reckoning with Scotland's role in the colonial project is necessary to begin the work of tackling racism and anti-blackness that still affects everyone."

The North British Rubber Company

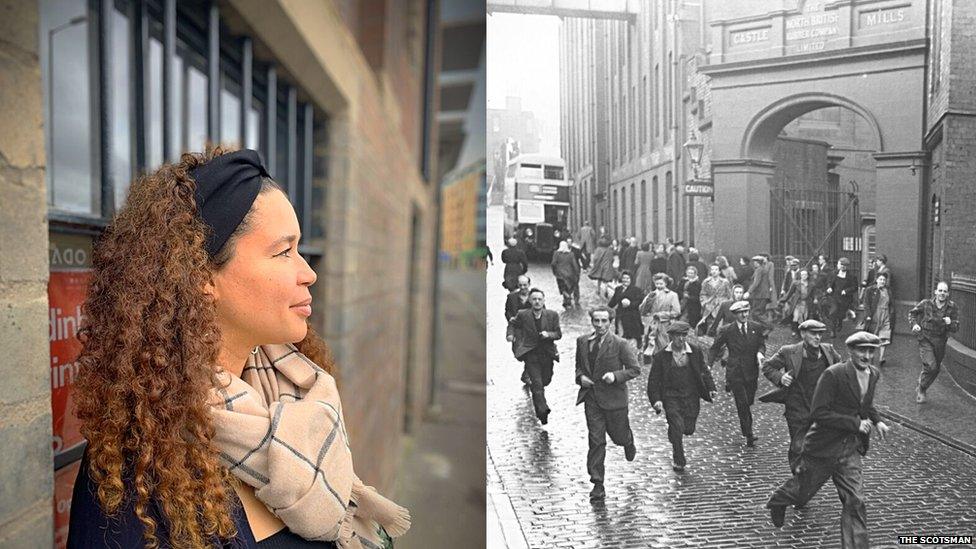

Alberta Whittle outside what remains of the North British Rubber Co alongside a picture from its heydey

The former factory employed more than 8,000 people at its peak, producing the first Hunter Wellington boot, tyres, golf balls, hot water bottles and other rubber products.

The Fountainbridge building underwent a multimillion-pound transformation and earlier this year became the new home to Edinburgh Printmakers.

Trench warfare

Whittle's film, "What sound does the black Atlantic make", links rubber manufacture in Scotland with Caribbean and African regiments involved in the war effort. The artist calls these men "collateral".

She explains: "The North British Rubber Company made money through rubber wellington boots used throughout World War One in trench warfare. The trench boots made here connect with who was in the trenches."

Production line workers making wellington boots at the North British Rubber Company in Edinburgh

For Whittle, rubber manufactured goods were one of the ways Scotland became complicit in, what she described as, "an exploitation of British colonial subjects".

She asks: "Who was doing the dirty and dangerous work of war, external? We find people from marginalised backgrounds, working-class people, or people from the ex-colonies across West and South Africa and the Caribbean.

"Service for your country did not transform these people into valued members of Britain. Following World War One, the race riots of 1919 saw black people deported back to the colonies, in spite of their service.

"After World War Two, people from the Commonwealth arrived in Britain, willing to help repair the mother country and they again become disposable."

The ex-troopship "Empire Windrush" arriving at Tilbury Docks from Jamaica, with 482 Jamaicans on board, emigrating to Britain

Whittle adds: "The Windrush catastrophe sees these same people being silently shipped off.

"That's a way for me to connect the work again to the history of this building. Rubber is a shock absorber. These people are still withstanding all of this shock."

Looking backwards, looking forwards

A sculpture based on the Roman god with two faces, Janus - one looking forwards and the other looking backwards

One of the exhibits is a terracotta sculpture inspired by Roman mythology. Whittle says: "Janus is a deity who looks backwards and simultaneously forwards. That's a provocation to think of the importance of history - remembering the past so we can move forward without repeating mistakes."

The artist says Scotland's "cultural amnesia" means the country does not look back at its role in history

The artist adds: "Scotland has colonial amnesia, not looking at the fact that Scots have been involved in Colonialism and participated in slavery. Scottish cities and streets are built on the bodies of black and brown people working in plantations or who came here to rebuild the country following war.

"For me this piece is a reminder that history is a haunting and we should offer hospitality to these ghosts of history."

Everyday objects telling stories

Three prints, depicting slingshots and musical instruments, represent music travelling across the Atlantic

Whittle visited the North British Rubber Company archives in Dumfries where the archivist mentioned the phrase "Gutta Percha".

This is a form of latex, derived from tree sap, used in the manufacture of rubber goods at the Edinburgh site.

"In Barbados we know that word, guttaperc, to mean a catapult or a slingshot. The way this word emerged between Barbados and Scotland really fascinated me.

"Within each print there is a guttaperc which is broken. It's pictured with a tuning fork. That's meant to reference the way sound and musical traditions move across the world."

The prints are made in layers of rubber, silk screen print and laser cut perspex

An assortment of objects comes together to tell a story of migration across the Atlantic

The artist's installations turn everyday objects into symbols which come together to form a story.

Whittle says: "On first gaze these elements might look like strange things to bring together: soap, washing basins, parachute silk, but each one of these elements tells a particular story.

Parachute silk represents waterways where Afro-Caribbean people historically crossed oceans - both willingly and against their will

Blue carbolic soap - or cake soap - has been used by Caribbean people in the past to lighten their skin, according to the artist

"This Jamaican blue soap can be used for laundry but is also used to lighten skin. There's an idea in migrant communities about respectability, that if you lighten your skin as a black person then you will be safe.

"The reason why I have connected these shapes, the silk, the basins, the soap - connects the work with the original site of Edinburgh Printmakers - at an old Steamie at the top of Leith Walk - but also with this idea of the whitewashing of history.

"There's a constant erasure and washing of history but we don't have clean hands. We know that we are sitting in this time of black and brown people being on the front line."

The free exhibition, Transparency, external, runs at Edinburgh Printmakers until 5 January.

- Published7 October 2019

- Published2 October 2019

- Published23 August 2019