Salt harvesting: Turning sea water into 'white gold' in a Fife village

- Published

Darren Peattie said he wanted to celebrate St Monans as the true home of salt

Salt harvesting is being revived in a Fife coastal village - 200 years after the industry ended in the area. The East Neuk Salt Company plans to produce two tonnes of artisan sea salt every month from February in St Monans.

In the 1790s, salt was Scotland's third-largest export after wool and fish.

It was so valuable that it was referred to as "white gold", with companies willing to burn eight tonnes of coal to make every tonne of salt.

The remnants of nine salt pan houses and a windmill can still be seen at St Monans.

The village has had salt pans since the 17th Century, although those remains date back to the 18th-Century, when they were built by the Newark Coal and Salt Company.

The windmill is the last one remaining one in Fife, and has since been renovated as a tourist attraction.

In the industry's heyday it would pump the sea water into the salt pans, which were then heated by coal. The water was boiled until it evaporated and left salt.

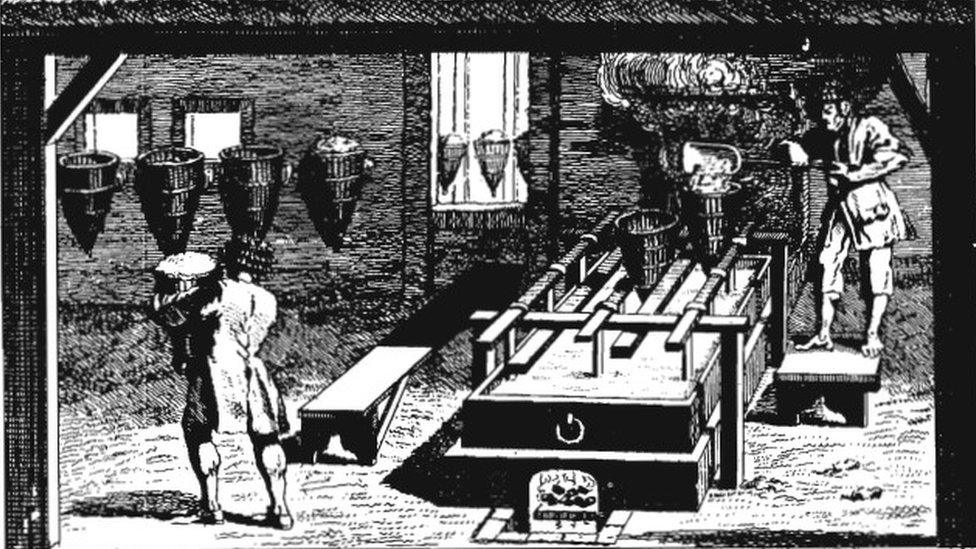

An illustration by William Brownrigg showing 18th Century salt making

However, the industry eventually ground to a halt due to competition from sun-evaporated salt from Spain.

Now Darren Peattie is reviving the salt-making tradition in the East Neuk of Fife.

The 36-year-old said he had been forced to leave St Monans when he was 17 in search of work.

He said: "My passion is to bring industry back to this area.

"I left 19 years ago for a corporate finance job in London because there were no jobs here, but I've come back now to fulfil my dream."

Darren Peattie will suck 2.5 tonnes of water from the Firth of Forth every day to make the salt

Mr Peattie will collect 2,500 litres (2.5 tonnes) of water a day from the Firth of Forth at Elie, using a hose to suck it up into a bowser tank. He will then drive it back to base in St Monans, three miles away.

"St Andrews University has tested the water and it's come back as Grade A, so the mineral content is perfect and the pollution is non-existent," said Mr Peattie.

"I can see why it was called white gold in the past. It's absolutely incredible."

The water is put through a filter which is finer than a human hair to get rid of any microplastics, then goes into a vacuum evaporator.

A sleeve, heated by gas, brings the water to 45C. It takes a few hours to turn the water into brine, which is then poured into crystalliser beds.

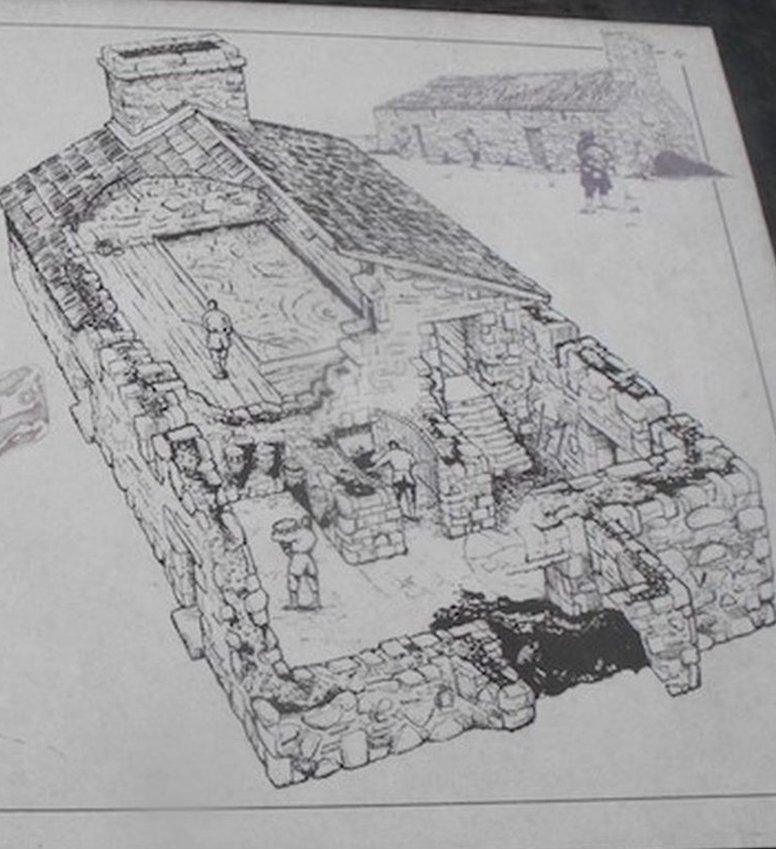

An illustration showing what a salt pan house looked like in the 18th Century

Mr Peattie said the process was like filling a bath with sea water and then heating it from below.

"Crystals and salt flakes start forming on the top of the bath water. When salt forms it gets heavier than water, so you get beautiful crystals and pyramid flakes sinking to the bottom.

"When you have a volume of salt at the bottom you get a stainless steel spade with holes in it.

"The brine drops off when you lift the spade and you are left with these beautiful salt flakes."

Remnants of the old salt pan houses remain at St Monans

These flakes are then put through the drying process, where they are spread out on hundreds of trays and put into a special oven for 40 minutes.

Mr Peattie has spent almost £160,000 on the equipment to produce the salt, and says some Michelin star restaurateurs have already expressed an interest in buying the product.

He hopes that his workforce will eventually grow to 20 people.

There are two other salt production companies in Scotland: Blackthorn Salt in Ayr and Isle of Skye Sea Salt Company.

Mr Peattie also plans to reconstruct one of the nine old salt pan houses in the area to turn it into a visitor centre.

The St Monans salt pans were excavated in 1985

The old salt pans were excavated in 1985, but there is little left of the buildings that used to cover them.

The windmill was restored and reroofed, with new sails attached in the 1990s as it was turned into a visitor attraction.

Mr Peattie said: "I want people to come into the village, see the old heritage site, develop an understanding of how the salt industry once worked, then move up to our new premises and learn how salt has moved on."

And he added: "The ultimate aim is to link the past to the present and celebrate St Monans as the true home of salt."