How Kirkcaldy became a new home for Polish war veterans

- Published

The Polish Club in Kirkcaldy opened in 1953

The Polish Club in Kirkcaldy, Fife, has been a centre of social and cultural life for almost 70 years. It was founded by veterans who were unable to return home after fighting in World War Two.

The club still provides an extended family to the children and grandchildren of those soldiers - along with a new generation of Polish migrants.

The community is now trying to buy the building before it goes on the open market. Here, we look back at some of the stories of the club's members.

Zygmunt Jaworski arrived in Scotland after WWII in 1945 as he was unable to go back to Poland

Zygmunt Jaworski arrived in Scotland in 1945 after serving with the 1st Armoured Division during World War Two.

Because he had fought for the Allies against the German forces, he was unable to return home to his wife Anna and daughter in Poland.

He set up a new life in Kirkcaldy, marrying a Scottish woman, Betty, and working as a miner and then a bus driver for Alexander and Sons.

Zygmunt became one of the founding members of the Polish Club in 1953 and spent most of his time there, when not at work.

His granddaughter Renata was aged 20 when she left Poland for Scotland to meet Zygmunt for the first time in 1974.

Zygmunt Jaworski and his wife Anna pictured in 1935

Now aged 66, she explained: "My grandfather went to war in 1939 and never returned because of the Soviet pact.

"He and his fellow ex-combatants were treated like spies because they had been fighting for the allies. So they stayed in the UK because they weren't allowed to return home.

"My grandmother thought he was lost and only heard decades later through the Red Cross that he was alive and living in Scotland."

At the beginning of the 1970s there was a change of government in Poland, and people were allowed under special circumstances to travel from Poland to visit relatives.

Her mother Halina had a job, so Renata decided that she would make the journey from Warsaw to Kirkcaldy.

"It was an emotional adventure and although I was alone, I wasn't scared," she said.

"Life in Poland was very difficult. There was a shortage of everything and it was a very hard life.

"You could get bread, oil and vinegar - but for everything else you had to know someone.

"The economy was in tatters and everything was done through bribery. I remember even having to bribe a porter to visit my mother and sister when they were both ill in hospital."

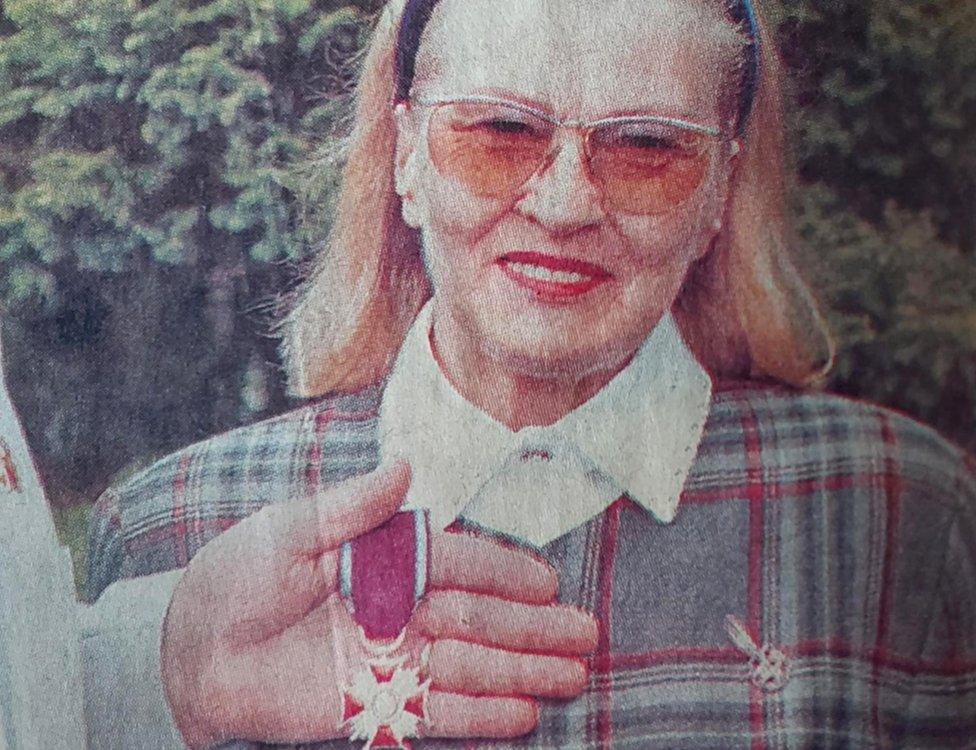

Halina Jaworska received the Silver Cross of Merit by the Polish Consul General on behalf of the country's president for her involvement in the Polish Club

Renata said it was "fantastic" when she met her grandfather, who was waiting for her at the train station with her new "Scottish grandmother" - Betty.

She said: "It was freedom when I arrived. It was brilliant and nobody was looking over my shoulder any more."

Renata's mother, Halina Kalinowska, followed her to Scotland in 1976.

Halina, now 83, said that her mother Anna had thought that Zygmunt had disappeared when he did not return from the war.

"She was in a terrible situation," said Halina.

"She had me to look after as a baby and her sick mother, and she had a job working very hard at the Polish railway. It was very difficult and hard for her.

"She was very much in love with my father and thought he had perished in the war. She missed him terribly and only had one picture of him."

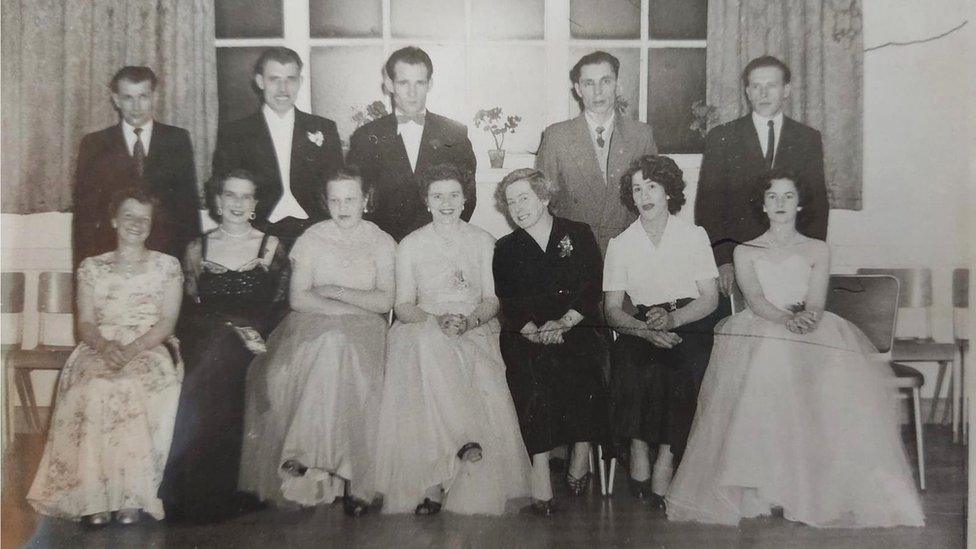

Saturday evening dances at the Polish Club in the late 1950s

It was only in the 1960s that Anna found out her husband was still alive and was living in Scotland.

"She was very unhappy when she found out, but also understood because soldiers who had been fighting for the allies were not allowed to return to Poland."

After being reunited with her father, Halina set up home in Kirkcaldy to look after him and his Scottish wife until their deaths.

Halina added: "In 1981 my mother came on my invitation to visit my grandfather and his new wife in Scotland and were great chums.

"She accepted that he had made a new life without her and I remember finding them in the kitchen having put brandy in their coffees sitting singing old songs together and having a great time."

Renata remembers being taken by her grandfather to the Polish Club, where he played a lot of chess.

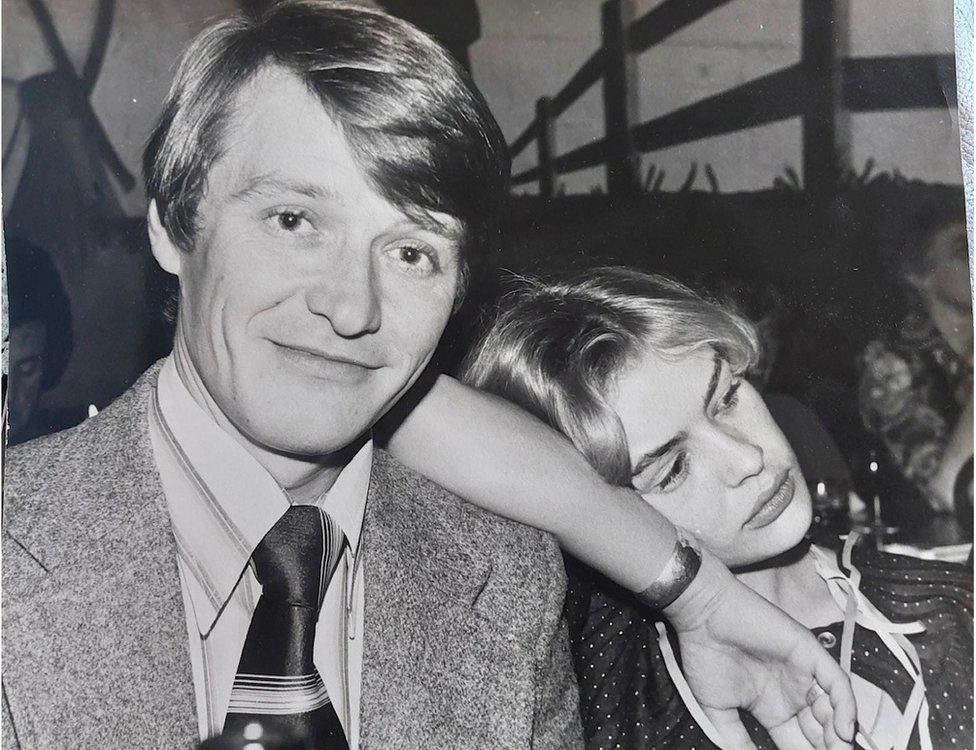

Renata and Zygmunt had their wedding reception at the Polish Club in Kirkcaldy

That was where she met her future husband, Zygmunt Lopatowski.

His mother had ended up in Kirkcaldy after being taken prisoner in Poland in 1940 and then taken to Siberia.

Renata, who had her wedding reception at the Polish Club, set up a Polish school in the building. She is now vice-chairwoman of the Polish Club.

"We all have a very emotional link to the club and cannot imagine it closing," she said.

"My husband and I volunteer a minimum of 20 hours a week to the club as it is a very important place for us."

There was a ladies section at the inception of the Polish Club - this is all the wives and daughters of the founding members at the club in 1985

The club still hosts events and its chef serves a range of traditional Polish food such as bigos, which is cabbage with meat, Pierogi, pastry filled with meat or cheese, sausages and breads.

Its members are now trying to raise £300,000 so they can buy the building under the community right-to-buy scheme.

John Hamilton, the Polish club chairman, said the owners were looking for £600,000 for the building, but that they had it valued locally at half that price.

The Polish Ex-Combatants Association, which is selling the property, said it did not want to comment.

"We have 160 members and it would be a great loss to them if it was sold," said Mr Hamilton.

"It is a way of drawing people together and there is a huge emotional attachment that spans right back to WWII."

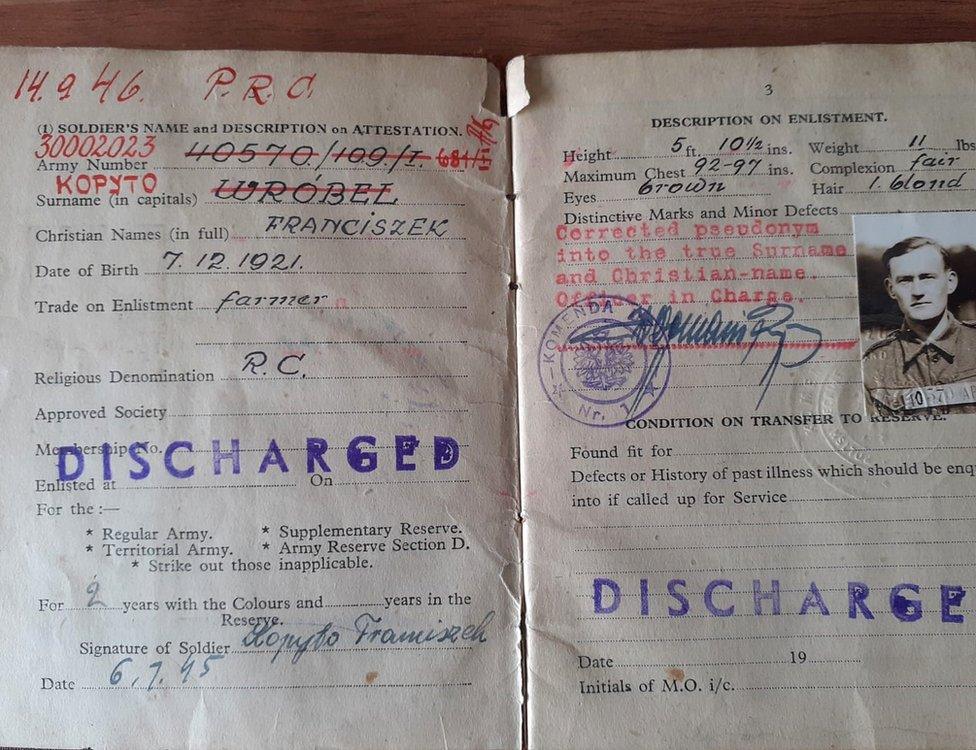

Francziszek Kopyto gave a false name when he was conscripted - but his papers were amended with his real name at the end of the war

Sandy Kopyto, 68, whose father Francziszek Kopyto was also a founding member of the Polish Club, had been conscripted to fight for the Germans during the war.

He was just 17 years old when he was taken from his parents' farm in Wierzbie, in the Silsesia region of southern Poland, in 1939.

When he got the chance he surrendered to the allies and ended up in Fife, where he married a Scottish woman.

He returned home for a visit in 1973 when he was allowed back into Poland.

Sandy said: "I was in the car when we arrived at the farm and we saw this little old woman shuffling down the path.

"My dad said: 'Oh my goodness that's my mother.' He didn't recognise her because it had been so long since he had last seen her as a teenager."

Sandy said his father rarely spoke about his experiences at war, apart from recalling that he had been shot in the foot.

But he added: "He always remembered when he was taken away from the farm and his mother telling him: 'When you're looking down your rifle remember the person has a mother who is waiting for him to come home'."