My grandpa founded Golden Wonder but I never saw him eat crisps

- Published

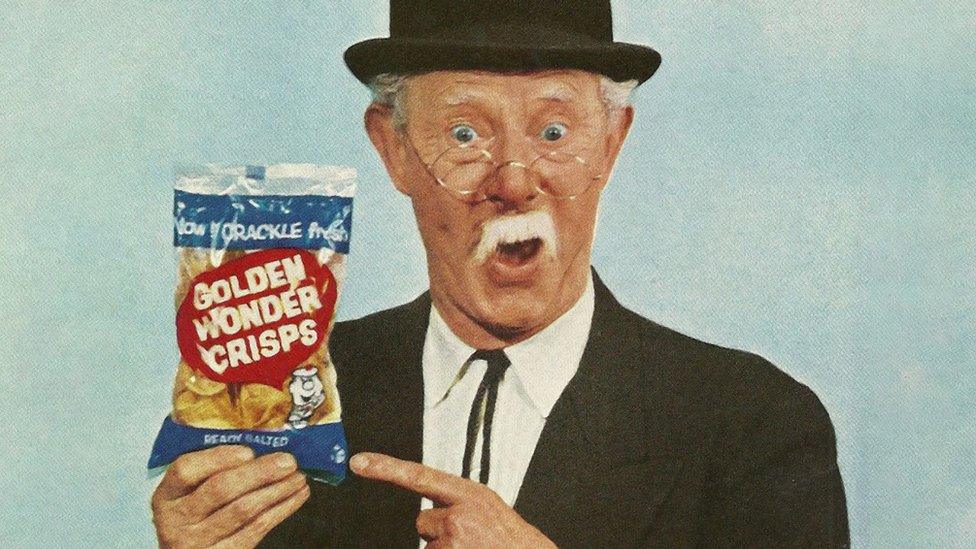

By 1964 Golden Wonder was the biggest crisp company in the UK

Most of Golden Wonder's historic documents and files were lost in a fire years ago but now as it marks its 75th anniversary the founder's granddaughter has spoken for the first time about how it all began.

William Alexander was working as a baker in Edinburgh in the 1940s when he came up with the idea which was to transform his fortunes.

After finishing his morning's work, he didn't want the machines to be redundant so he started dropping finely sliced potato into the deep fat fryers, which were normally used to make doughnuts.

William started making big batches of crisps which he delivered all over the Scottish capital.

The business took off rapidly and by 1964 Golden Wonder was the biggest crisp company in the UK.

It also made the UK's first flavoured crisp when it started selling cheese-and-onion in 1962.

William Alexander started making crisps in Edinburgh with Golden Wonder potatoes

The rise and fall of the crisp brand is a story that is not well known.

It began 75 years ago - in 1947 - when William moved his shop from Stockbridge in Edinburgh to nearby Well Court Hall in the Dean Village area.

His eldest son Norman was a radiographer at the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh but reluctantly gave up his medical career to help his father when the business started getting busy.

He even sent Norman to North America to buy some machinery to de-starch the potatoes.

Within a few years William outgrew his premises again and moved to a new purpose-built factory in the Sighthill area of Edinburgh. It opened in 1952, with 200 staff, and was supplying crisps all over Scotland.

Jennifer Fraser remembers her grandfather taking her to his factory when she was about six.

"He took a big polybag full of crisps off the line and gave it to me," the 73-year-old told the BBC. "It was hot against my body and the smell of salted crisps was amazing.

"I thought I was the bee's knees. They are lovely when they are still hot."

William Alexander cutting the turf in 1963 at Broxburn before his factory was built

Jennifer said her grandfather took pride in his crisps.

The company was named Golden Wonder after the variety of potato he first used and thought they were the best.

His granddaughter said: "He only used a certain type of potato and everything was the best quality.

"He was very proud of what he had achieved, it was his baby and he was really pleased with it. It all came from very hard work."

William Alexander (L) on a ship with his brothers, Joe, Robert and George

Jennifer said William Alexander was a quiet man.

"He didn't give anything away," she said. "He was old fashioned in that way, very reserved."

"He never mentioned about liking crisps and I never saw him eating them," Jennifer said.

"My dad was the same - he had a bad stomach and was plagued with ulcers, so he never ate crisps either."

William Alexander had two crisp factories in Scotland and two in England

William died from heart problems in 1973, at the age of 71. He and his wife Margaret had three children - Norman, Sheila, and Robert, who was Jennifer's father.

At the factory in Sighthill he named two of the machines Oor Wullie and Oor Maggie, after himself and his wife.

As the company's success continued, William built another factory in Broxburn, West Lothian, in the early 1960s.

By 1964 Golden Wonder was producing crisps at four sites - the two in Scotland, and others at Widnes and Corby in England.

The company later branched out into making salted peanuts and in 1977 it launched the Pot Noodle at its Welsh site in Crumlin.

Golden Wonder cheese and onion was the first flavoured crisp in the UK

As a pioneer of flavoured crisps, Golden Wonder's green packet for cheese-and-onion was adopted by its competitors.

But decades later, there was controversy and confusion when Walkers started selling cheese-and-onion in a blue packet.

Miriam Holland, a spokeswoman for Tayto - which now owns Golden Wonder - said the packets should "of course" be green because that was the colour of onions' shoots.

"Walkers came along and changed the colours around because they wanted to be different and it caused uproar," she said.

"It still causes discussion on social media from time to time."

Walkers took over as the UK's leading crisp manufacturer as Golden Wonder struggled to compete.

It closed its last Scottish factory in Broxburn in 1987 and there was a £54.6m management buyout in 1995 before the company was acquired by Bridgepoint Capital in 2000 for £156m. It went into administration in 2006 and a few weeks later the company was bought by Irish company Tayto.

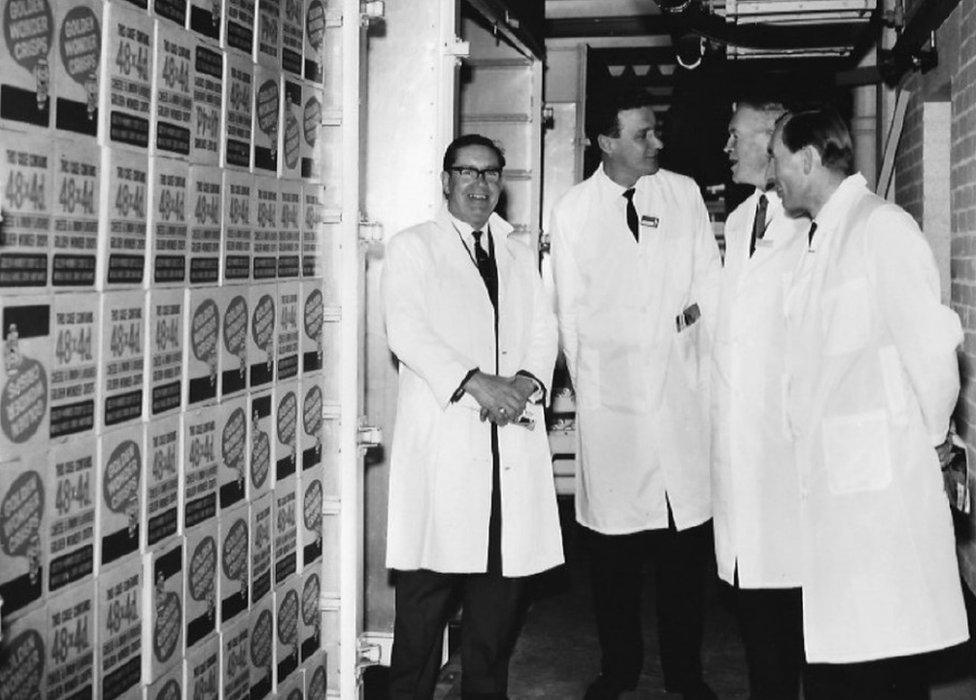

Employees at Golden Wonder

A fire at the Golden Wonder Factory in Corby in 1989 destroyed a lot of the company's historical documents and photographs.

Jennifer Fraser's son Alex, who died in January at the age of 56, had been keen for his family's history not to be forgotten and gathered as much information as he could from other family members.

In an email exchange with author Debbie O'Connor he told her that William Alexander had been born in 1901 in Armadale.

"After leaving school he went on to work and train as an electrician in the coal mines of West Lothian," Alex wrote.

"My grandfather, Robert, was a baker and was always looking at ways of getting out of the mines.

"I know William and my grandfather worked 18 hours a day and did not get to spend much time with their families."

Andrea and Alex Fraser at the Golden Wonder factory in Scunthorpe in 2018

Ms O'Connor, who is writing a book about Stockbridge called Walking in the Footsteps of Ghosts, said Alex believed William Alexander bought his bakery in about 1939 or 1940 on a site which is now home to a supermarket.

"My gran did not work in that shop as she had her own business in Stoneyburn in West Lothian called Central Radio," Alex wrote.

"William also worked there fixing radios and televisions as he was an electrician, mainly doing this at night, after the bakery was closed for the day.

"He was making crisps in the back of the bakery after all the work was done for the shop."

One of the earliest addresses for Golden Wonder was at Well Court Hall in the Dean Village area of Edinburgh

Robbie Mitchell, a reference assistant at the National Library of Scotland, researched old directories around the address where the supermarket is now located in Stockbridge.

While there was a bakery near 46 Raeburn Place, it might not have been the one where Alexander worked.

"While it is generally written that Alexander began cooking crisps in Stockbridge, unfortunately a precise address as to where this happened is sadly lacking," he concluded.

He said the earliest references to the Golden Wonder crisp tended to be job adverts which gave an address at Well Court Hall, Dean Village.

A less obvious effect of the work that was done there emerged 50 years later when the clock in the hall's tower was being refurbished.

When it was examined, experts found that it had stopped working because it had become so clogged up with all the fat from making crisps.