How I found success despite foetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- Published

Carol Hunter spoke about her experience of adoption and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) - and how she achieved success

Carol Hunter not only enjoys being overscheduled - she says it's a necessity.

The 39-year-old, who was adopted as a baby - is a parent, has a full time job at Fife College and leads a programme of support for adopted children for the charity Adoption UK.

The result? "My Outlook calendar is an absolute nightmare," she said. "I need to remind myself to take my lunch or I'll work through and forget to take it."

Carol's highly active mind, she says, stems from foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), external - a range of physical and mental problems in a baby caused by the mother consuming alcohol during pregnancy.

It includes hearing and balance problems, learning issues, problems developing social skills and impulse control.

Adoption UK estimates that up to one in 20 people, external in Scotland could have the condition.

Carol, from Crossgates in Fife, told the BBC if she wasn't cramming her days with activities the result could be far more harmful.

"People think it's a stressful life but it's a way for me not to spend a lot of money or rearrange my house," she said.

"If there's a change in routine it totally throws me. If an event gets cancelled I don't feel prepared for what happens next."

Carol found out about her condition when she learned she was adopted in her late teens.

Her parents, she said, had tried to protect her from the reality of her biological mother's behaviour as well as the stigma surrounding FASD - although the signs of the condition were there as a child.

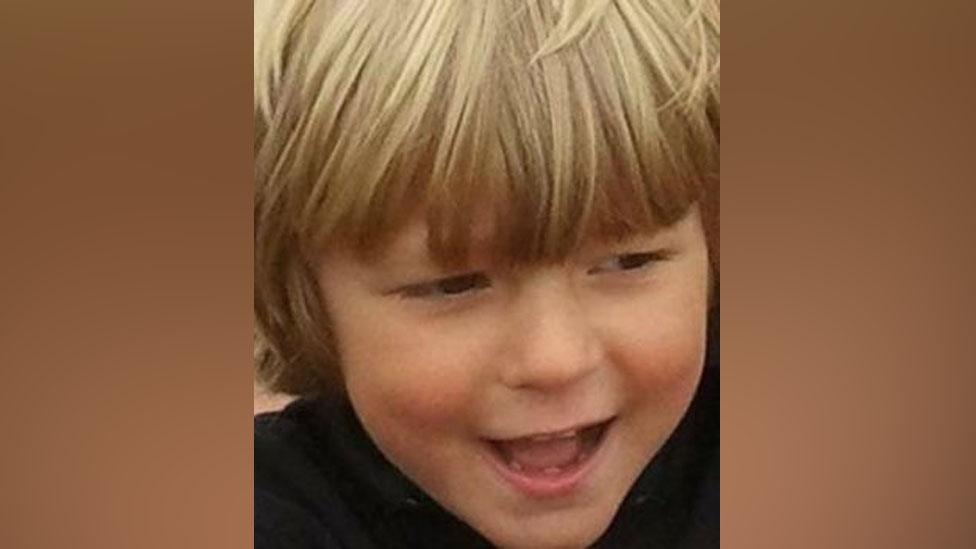

Carol struggled to make friends in school and found certain subjects difficult

At school she struggled with subjects like maths and science and found it difficult to make friends, while her classmates would tease her for being easily led on.

As a result, Carol said her parents "wrapped her in cotton wool" and restricted her social life.

"It was the 1980s," she said. "Mum didn't want people to know because people would assume she drank when she was pregnant.

"When I found out it pieced a lot of puzzles together. I asked mum if she knew why I was acting like that - she just thought I was a typical teenager."

'I thought I wasn't capable'

In 2001, Carol's behavioural problems began to spiral out of control while at university.

Her academic struggles continued, she started drinking heavily and she was briefly homeless in her early 20s.

"As you get older it affects you differently," she said. "Although you might come across like a 20-year-old your social skills could be at the stage of an eight-year-old.

"When I was studying I had to constantly rewrite stuff to take it in. I didn't know that at first and just thought I wasn't capable of very much."

Carol received her masters degree more than 10 years after she first dropped out of university

Carol dropped out of her primary teaching course the following year and it took 13 years before she returned to academia.

She applied to college, prompted by her adoptive father, who died in 2014.

There, she opened up about her condition and found staff were highly supportive.

They helped her develop a learning support plan, which she said made the experience transformative.

"Looking back it's like I was a totally different person," she said. "My manager when I worked in the student association also pushed me outside my comfort zone to do public speaking.

"I wish there were more open conversations about it [FASD]. With people believing in you you can achieve things."

Carol and her manager pictured at the College Development Network's 2022 College Awards, where she won for health and wellbeing work at Fife College

Carol went on to university and graduated with a degree in social sciences, later securing a masters in crime and justice.

After her adoptive father died, she decided to look into her biological family - she discovered she had six younger siblings, one of whom had died at birth.

"I wish I hadn't looked into my birth family but it was right for me - I wish there were more open conversations about it," she said.

Support for adopted children 'vital'

Carol's experience, both with adoption and living with FASD, prompted her to take the role community engagement lead with Adoption UK Scotland, where she runs the #E Project - a series of skills workshops for adopted young people.

It aims to not only support young people to succeed academically, but help them find a sense of belonging among people with similar experiences.

Funded by the Scottish government, the project launched in August 2021 and has about 80 participants across Scotland.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Although the number of children being adopted in Scotland has generally decreased since 2015, recent figures from the Scottish Care Inspectorate, external also show there have been increases in the number of adoption breakdowns - both last year and in the first year of the pandemic.

In sharing her story, Carol hopes to raise awareness of the support adopted children can require.

She said: "I've had it said before there's now more support to get into education - and people say adopted people shouldn't be included because they got their 'forever home'.

"It just shows how much more trauma-informed they need to be. It doesn't mean you've not been in care. You've got education battles and social battles.

"A lot of people don't want to say they have been in care or are adopted because they feel people's opinion of them will change - projects like this help them feel a sense of belonging."

Fiona Aitken, Adoption UK Scotland director, added: "The existence of the #E project is crucial for organisations like Adoption UK Scotland to centre the experiences and voices of our children, young people and adults who have experienced the care system.

"We see it as a vital service for our community."

Related topics

- Published20 November 2020

- Published18 June 2019