Forgotten diaries show how illiterate baker became pioneering herbalist

- Published

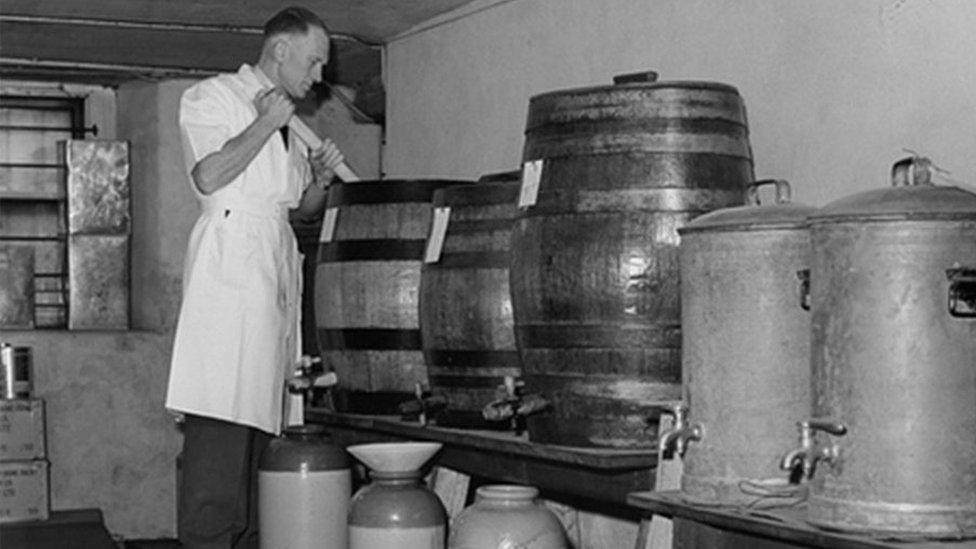

Lynda Melvin said she remembered her dad, Jack, mixing herbs in the basement of the store

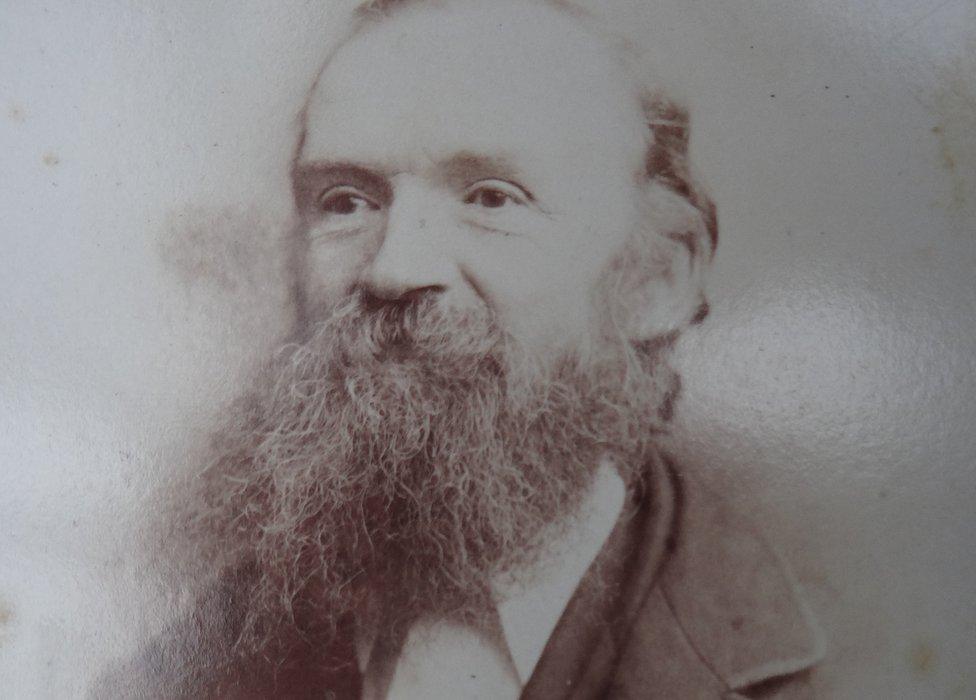

Forgotten diaries have been found which reveal how a chance meeting changed the life of an illiterate baker - who became a pioneer of herbal medicine in Edinburgh.

Fifteen-year-old Duncan Napier was delivering bread rolls when he struck up a conversation with lawyer John Hope, the grandson of the King's botanist.

Mr Hope took the teenager under his wing after being "shocked at his illiteracy, how he knew nothing about Christianity and that he drank alcohol regularly".

Some years later, he provided the funding which enabled Duncan to open Scotland's first herbal apothecary, Napiers, in 1860.

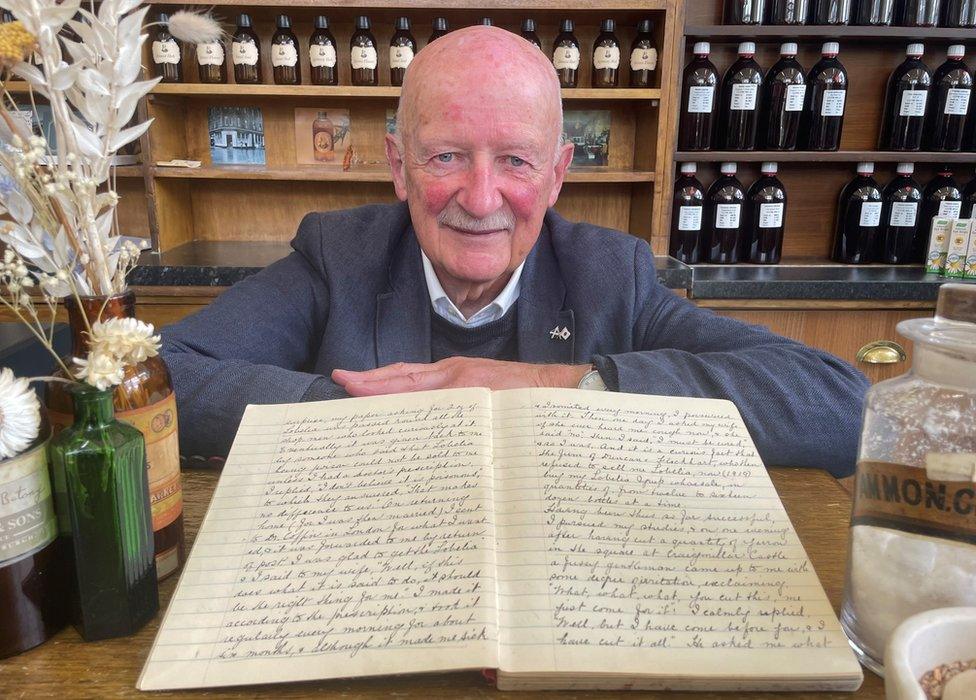

The story of their chance meeting has been revealed for the first time in forgotten diaries - each more than 100 years old - which were found recently by his great-granddaughter, Lynda Melvin.

She is the daughter of Jack Napier, the third generation of the Napier family to own the Edinburgh herbalist business.

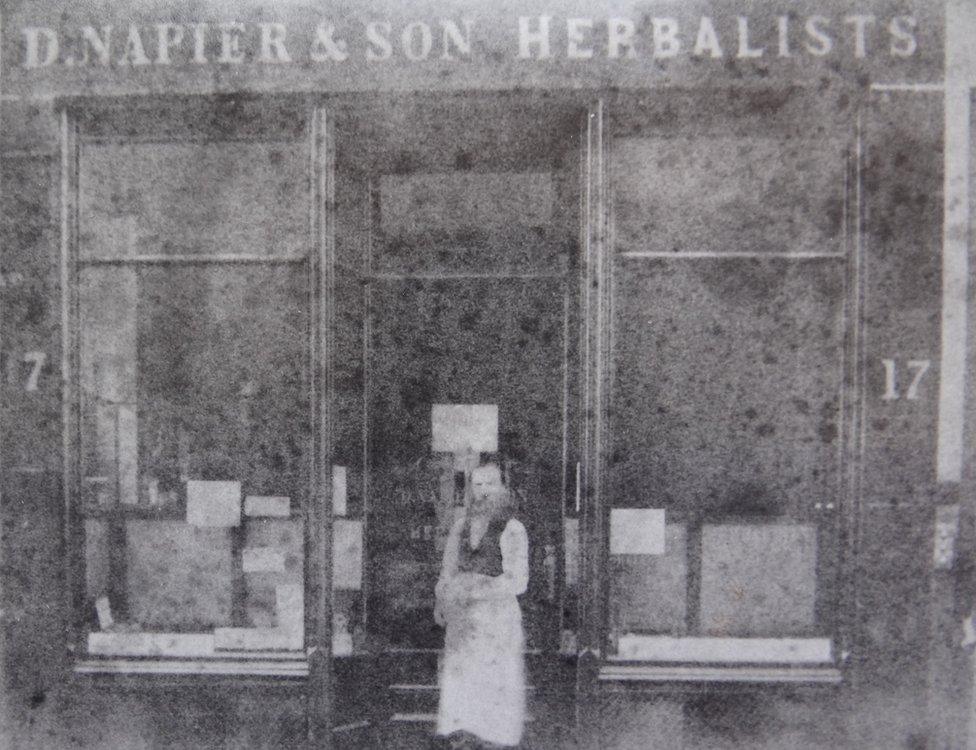

Duncan Napier opened his herbal apothecary in 1860

In 1978, shortly before his sudden death, Mr Napier gave the two old notebooks to his daughter.

Lynda, 74, told BBC Scotland: "I put them on a shelf and forgot about them without ever reading them.

"The notebooks sat on a shelf for decades and could so easily have been thrown out.

"I came across them recently and when I opened them I couldn't believe all the secrets inside. To think how close we came to losing all this history doesn't bear thinking about."

They tell how Duncan Napier was mentored by Mr Hope over the weeks and years after that chance encounter.

The only surviving picture of Duncan Napier outside his shop in Edinburgh

The eminent lawyer, whose grandfather created the UK's first Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, persuaded the teenager to go to night school, join a church and renounce alcohol.

The pair kept in touch and when he learned about Duncan's interest in plants, Mr Hope persuaded him to attend scientific botany classes and to then join the Edinburgh Botanical Society.

Duncan, who had been an apprentice baker since the age of nine, had developed a cough from the flour dust he inhaled during his years in the job.

Looking for a cure, and inspired by Mr Hope, he used herbs to create Lobelia Cough Syrup.

The result was so successful that it inspired him to become a herbalist and to open a small shop - Napiers in Lindsay's Close, off Bristo Street.

He soon moved across the road to open a larger shop in Bristo Place, where it still remains today. There are also now branches in Bathgate, West Lothian, and Glasgow.

Eric Melvin analysed handwriting to work out who had taken Duncan Napier's dictation

Lynda's historian husband, Eric Melvin, said the diaries held an "incredible story".

"Duncan had a very tough upbringing and we hear how he went on to overcome illiteracy to help Edinburgh's poor," Mr Melvin said.

"In those days there was no NHS and you had to pay for medicine. He would be very affordable, and sometimes didn't charge for his services.

"He catered for the poor and he also talks about having queues still outside his shop at 10pm at night."

He said the notebooks contained details about the first patients that he treated, which made "astonishing" reading.

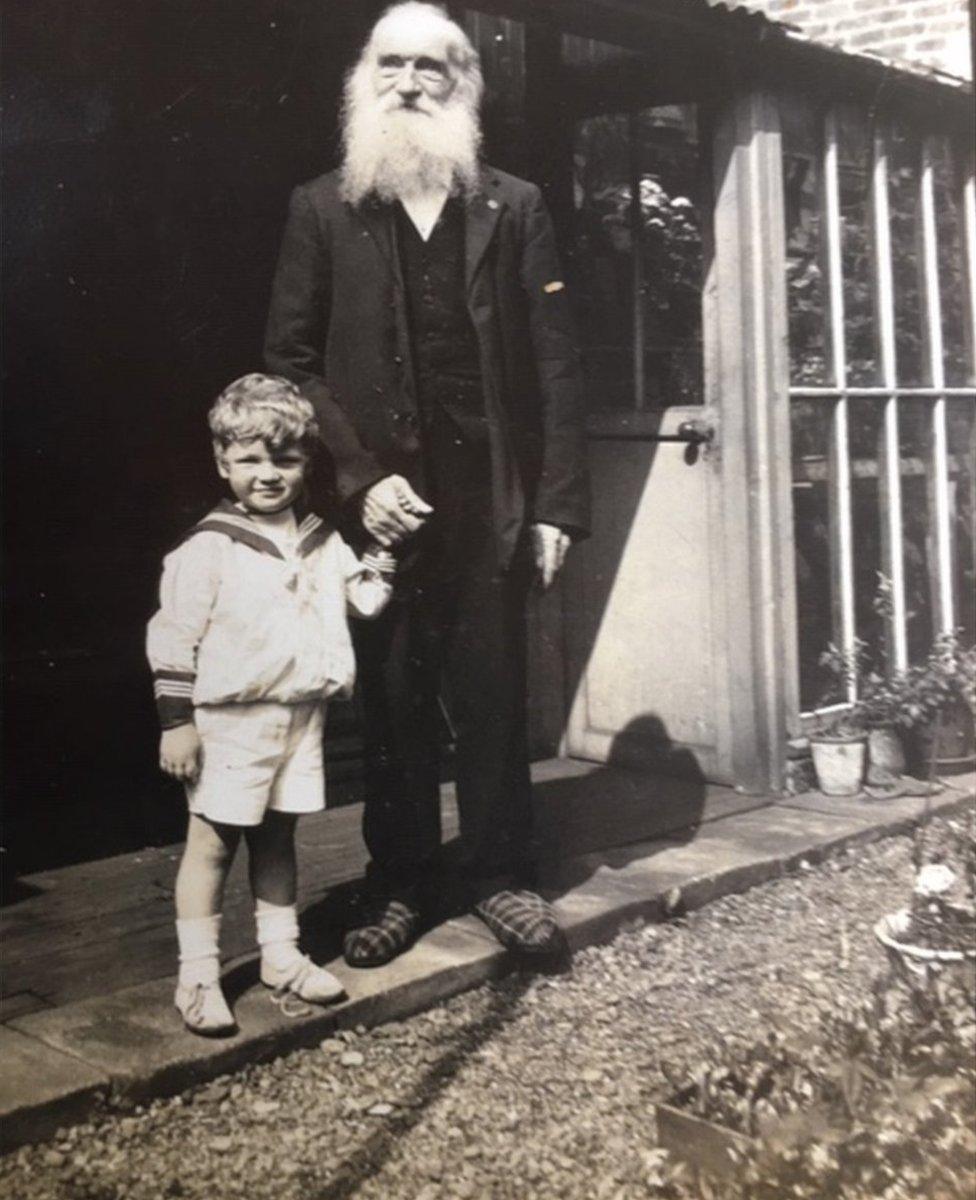

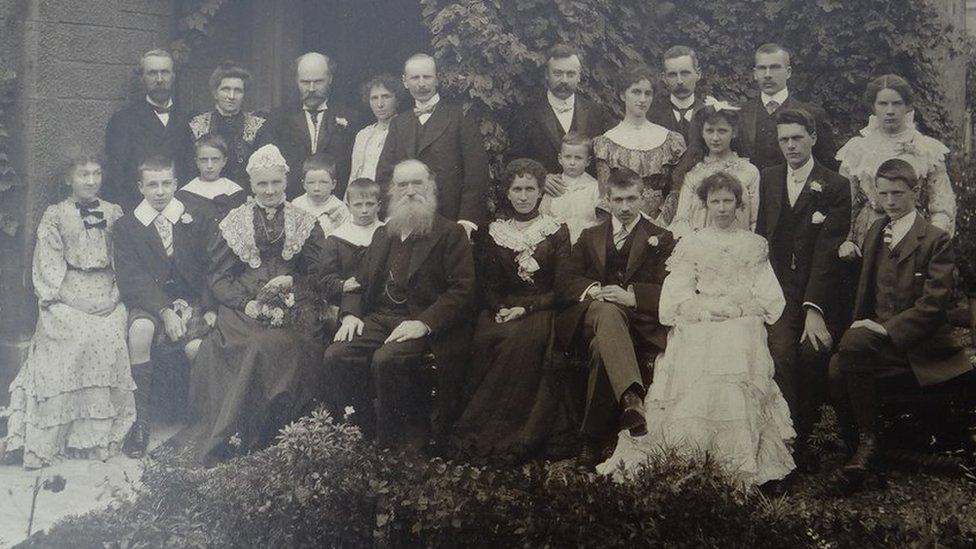

Duncan Napier with Lynda's dad Jack, aged four in 1918

"One man kept falling on the ground and having fits and appeared at Duncan's clinic as a last resort before conventional doctors were going to send him off to the mental asylum," he said.

"Duncan realised it was a common complaint and made him a mixture to treat a tapeworm.

"He ended up passing a tapeworm that measured 16 yards (14m) long."

Another woman with severely ulcerated legs had been told her legs would have to be amputated - but the diary recorded that she was cured by a herbal remedy.

However, she could not afford to pay so she offered to sit in the shop window and show off her legs as an advert for the successful treatment. Her offer was declined.

Jack Napier mixing herbs in vats in the basement of the store in Edinburgh

Mr Melvin said the journals told how Duncan, who was born in February 1831, was the illegitimate son of Helen Alexander, a young Edinburgh widow.

As an infant he was taken in by Edinburgh publican James Napier, who was "almost certainly" his natural father.

Duncan described an abusive childhood at the hands of a cruel, alcoholic step-mother.

In about 1840 the family moved to the village of Coltbridge where James Napier took over the tenancy of the local pub.

This was where Duncan first developed his love of plants by looking after the pub's garden.

Duncan Napier celebrating his golden wedding anniversary at his house in Sciennes

He worked for a local market gardener before becoming an apprentice to local baker John Binnie by 1845, which was where he was working when he met John Hope.

After the launch of Napiers in 1860, the business grew and developed an international reputation.

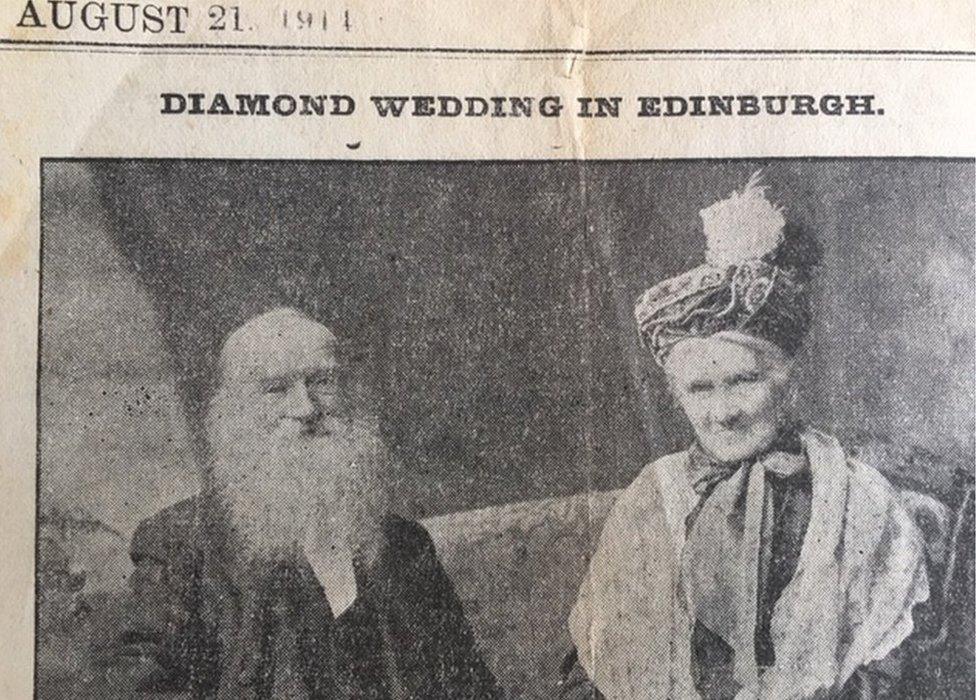

Duncan had married his wife Joan in 1854, and over time their sons Andrew and Duncan junior - Lynda's grandfather - joined him in the business.

Joan died in 1915, the year after their diamond wedding anniversary, and Duncan passed away in 1921 at the age of 90.

Mr Melvin said he had established that the newly-discovered diaries had been dictated by Duncan by comparing handwriting with signatures on death certificates.

Duncan and Joan celebrated their diamond wedding in 1914

The first diary, which contained memories about his early life, was dictated to his eldest son, Andrew, in 1914.

The second was dictated to Duncan junior in 1918, and focused on how successful his patents and cures had been.

Napiers was run by Duncan junior, and then by his son Jack until his death in 1978.

The business then passed from the family and, after some difficult years, was rescued by Edinburgh herbalist Dee Atkinson and her partner Monika Wilde.