How a hospital meeting inspired Wilfred Owen's WWI poetry

- Published

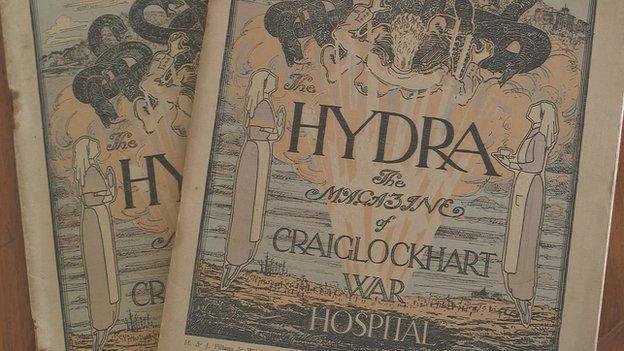

Staff and patients in 1917 posing in front of Craiglockhart hospital which was set up to treat shell-shocked soldiers in WW1

The horrors of World War One were expressed by many of the soldiers who fought in the conflict but few did so with such power and eloquence as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon.

Owen is often regarded as the best wartime poet of his generation but his potential may never have been realised had he not met Sassoon at Craiglockhart, a hospital in Edinburgh for shell-shocked soldiers.

While recovering from Covid-19, American journalist and author Charles Glass used his isolation to delve into their poetry and reflect on their lives.

The hospital featured in the Regeneration novels by Pat Barker, which were published in the 1990s and later adapted for the cinema.

Glass was captivated by their story and set out to write the non-fiction version of Barker's acclaimed trilogy.

Wilfred Owen was killed in France just one week before Armistice Day in 1918

While researching, he found Owen's pairing with his psychiatrist encouraged him to write poetry and proved crucial to his recovery.

The book, Soldiers Don't Go Mad, is being launched at the site of the hospital, now a part of Edinburgh Napier University, later this month.

Glass explained: "That phrase comes from a poem by Siegfried Sassoon in which he wrote 'soldiers don't go mad unless they lose control of ugly thoughts'.

"There was a belief, widespread in the military and in civil society that soldiers were somehow above the weakness of mental illness that they would never become hysterical.

"But in fact, given what they went through, mental breakdown was a normal reaction to an abnormal situation."

Siegfried Sassoon was already known for his poetry when he was sent to Craiglockhart

Officially Sassoon, a decorated war hero renowned for his bravery on the Western Front, was sent to the hospital to be treated for shell shock.

However his admission was actually used as a way to defuse the tensions his public anti-war declaration had created and avoid having to court martial such a prominent figure.

Meanwhile, Owen had been admitted to the hospital after experiencing a number of traumatic events while fighting.

This included being trapped for days next to the dead body of a fellow officer.

During the years it was operating as a shell shock hospital Craiglockhart's small staff of doctors and nurses treated somewhere between 1,500 and 1,800 patients.

Nurses in Craiglockhart hospital which Charles Glass said was able to return more soldiers to duty than other mental hospital during the war

Patients at Craiglockhart were encouraged to be as active as possible.

And it was Captain Brock, Owen's doctor, who encouraged him to write.

Glass said: "Brock saw the mental breakdown of war as a continuation of the mental breakdowns he observed in industrial society where workers would have nervous breakdowns because of the pressure of work.

"He noted from his previous psychiatric practise before the war, that the best way of bringing people back to mental health was to get them to engage in productive labour of some kind.

"Not simply languishing in bed thinking about problems, but to actually confront their problems, overcome them and engage in life to become whole again."

Owen had read Sassoon's collection of poetry, The Old Huntsman, which had just come out.

Sassoon was already known for his poetry at this time and his most famous works included Suicide In The Trenches, On Passing The New Menin Gate and The Poet As Hero.

Owen confided in him that he was a poet as well. During their time together at Craiglockhart they developed a mutual admiration and helped one another improve their craft.

Glass said: "Craiglockhart was the leading institution for treatment of shell shock because the psychiatrists there believed in Freudian psychoanalysis rather than what was practised in other hospitals, which was electroshock therapy, cold baths, putting men in just to lie in bed and get over it quietly."

As a journalist Charles Glass has observed many different conflicts

Although it is hard to measure the success of physicians in treating the shell-shocked at Craiglockhart, Glass said it was able to return more soldiers to the front than other mental hospitals during the war.

He added: "It was down to the methodology of both Rivers and Brock treating the men sensitively, listening to their problems and telling them, convincing them, that they were normal men under abnormal circumstances.

"And that it was perfectly understandable - they were not cowards, as some in the military said."

Glass served as ABC News' chief Middle East correspondent from 1983 to 1993 and reported on significant events, including the Arab-Israeli war, the TWA Flight 847 hijacking and the Yugoslav Wars.

"I've observed many wars over the last 50 years. I had the advantage as a journalist that I could always leave when things got difficult, I could always withdraw from a frontline to save my life," he said.

He added that soldiers often do not have that luxury.

Mental anguish

Glass explained: "So many of them faced what was called the flight or fight impulse. Unable to go on fighting, because men die, and yet not wanting to run away, they broke down. That was what they had to deal with.

"As a journalist I observed these things. I didn't experience the same things that those soldiers did."

He said he hopes readers of his book will be able to better understand Sassoon and Owen's poetry and empathise with the mental anguish they went through.

"That empathy comes out very strongly in their poetry, particularly the sensitivity they had for the men under their command who suffered so much," he added.

Sassoon and Owen both returned to service after their time at Craiglockhart.

But while Sassoon was shot in the head and survived, Owen was killed a week before the war ended.

After the war Sassoon was instrumental in bringing his friend's work to the attention of a wider audience.

Owen's most celebrated poem, Dulce et Decorum est, was published posthumously.

It's title comes from a Latin phrase, meaning "It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country".

But Owen uses it ironically. He does not endorse the phrase but brands it "The old lie".

More than one hundred years later, it remains the most damning poetic response to the conflict.

"It was really the best poetry of the First World war," Glass said.

Related topics

- Published30 November 2015

- Published18 March 2014