'Old Firm' faultline is once again a political football

- Published

The Old Firm fixture goes back more than 100 years

What is so extraordinary about an ill-tempered football match that it has to be discussed at a government summit convened at the request of the police?

The simple answer is that the game was between Celtic and Rangers.

The Barcelona motto, "Mes que un club", meaning "More than a club", could also apply to these two Scottish giants.

They are institutions, split largely along religious, cultural and political faultlines. When there is fallout from a game, it can go far beyond the pitch.

Last week, following a Scottish Cup replay at Celtic Park, it did.

'Shameful' game

During a volatile match, which Celtic won 1-0, there were three Rangers players sent off, several touchline and tunnel confrontations and 34 arrests inside the stadium.

Police described the events as "shameful", with politicians and the Scottish Football Association also being highly critical.

Scotland's First Minister Alex Salmond later agreed to host a summit in Edinburgh following a request from Strathclyde Police.

So how did Celtic and Rangers arrive here?

Both clubs are known collectively as the "Old Firm" - a term of association, which unsurprisingly, is unpopular to some of their fans.

-1.jpg)

Celtic were founded by Irish Marist brother Walfrid

Although the origin of the label is not clearly known, it has become accepted that it refers to the commercial benefits that flow from the great rivalry.

Both clubs are from Glasgow - Scotland's largest city - but like other giants of world football, their appeal draws support from a worldwide fan base.

It is across the water, however, in Ireland, that the reference points of their bitter rivalry can be found.

Celtic were founded by an Irish Marist brother - Walfrid - and historically draw their support from the descendants of Irish Catholics who emigrated to Scotland after the Great Famine.

The club also has a substantial well of support across Northern Ireland and the Republic.

Rangers were founded by brothers Moses and Peter McNeil, Peter Campbell and William McBeath and have traditionally drawn support from Scotland's mainly Protestant community.

It also has a substantial support in the mainly Unionist Northern Ireland.

Although both clubs attract support from other sections of society, it is this religious divide which has come to define the fixture's 100 years plus history.

For many Celtic fans, their club is an integral part of the Irish diaspora, and embodies a unique Irish Scots identity that has overcome discrimination in employment, housing and education to fully play a part in modern Scotland.

Sectarian singing

Across the city, many Rangers fans see their club as "quintessentially British", with a pro-Union ethos which is often expressed through strong support for the monarchy and the country's armed forces.

The physical manifestation of these historical differences can be seen in the strips, flags and songs of both clubs.

But why should these cultural differences be a problem for an internationally famous derby match?

The answer, for some authorities in Scotland, is that they have fed a sectarian-fuelled hatred between the clubs' fans that too often leads to unacceptable levels of violence and anti-social behaviour.

Critics accuse both sets of Old Firm fans of sectarian singing, which would not be tolerated in any other social gathering.

They also claim the fixture lies at the root of high levels of alcohol-related violence on match days and that modern Scotland cannot, and should not accept this any longer.

The most infamous case of disorder came during the 1980 Scottish Cup Final when both sets of fans ended up on the field after Celtic had triumphed 1-0.

The resulting riot saw supporters attack each other and hurl bottles, cans and bricks, while mounted police charged the fans in a desperate bid to restore order.

With the full shame played out on live television, the fallout was profound.

In the aftermath, alcohol was banned from every ground in Scotland and the police presence at games was greatly increased.

Over the years, there have been other notable incidents involving players, referees and fans, but nothing on this scale.

Uefa fine

If the alcohol ban and eventual introduction of all-seater stadiums went some way to addressing the issue of violence, it did nothing to diminish the charge of sectarianism which has been continually levelled at both sets of fans.

In 2005, the then First Minister, Labour's Jack McConnell, hosted an anti-sectarianism summit after referring to the issue as "Scotland's shame".

There was much debate but it did little to diminish what critics perceived as the core problem.

Since then, Rangers have been fined twice by Uefa for sectarian chanting by some fans.

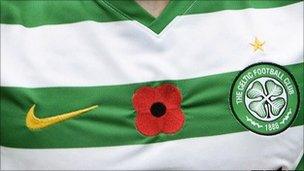

Some Celtic fans protested against the Poppy being used on the club's strip

One song - the so-called "Famine song" - has been ruled as racist by Scottish courts and also attracted widespread criticism from the Irish Republic.

Celtic have not been without their own problems too.

There was heavy criticism when a representative of one fans' group, the Celtic Trust, said chants about the IRA were "songs from a war of independence going back over a hundred years".

A section of fans, who call themselves the Green Brigade, also caused controversy when they unfurled a banner condemning the club's participation in the Poppy commemoration.

Supporters of both clubs could no doubt lengthen the crime count of their rivals, but in the eyes of critics, however unjustifiable it may seem to some fans, they are both as bad as each other.

In recent years, senior police have become increasingly bullish about the problems they have to deal with when the Old Firm go head-to-head.

Figures have been published which show a sharp rise in domestic abuse incidents and serious assaults during and after the fixture.

Jack McConnell held a sectarianism summit while he was First Minister

More recently, some senior police officers have stepped up pressure by calling for the fixture to be banned, or played behind closed doors.

There have also been claims, from police again, that the fixture will cost the country up to £40m this year.

In the wake of last week's ill-tempered Scottish Cup replay, Strathclyde Police requested a summit to address issues of Old Firm-related disorder.

Amid the continuing fallout on the field, what can Tuesday's meeting in Edinburgh achieve?

No doubt, the police hope it will lead to renewed efforts to reduce sectarian behaviour and violence and a rebuke for both clubs over recent on-field and touchline conduct.

But critics have accused them of blowing last week's events out of all proportion and lacking perspective in a bid to, perhaps, lever more resources during a time of budget pressures.

They also ask how can two football clubs be held responsible for wider social problems such as alcohol-related violence and anti-social behaviour.

Throw in the cultural baggage of both clubs, and the summit has an unenviable task.

Whatever the outcome, the Old Firm game is, once again, a political football.

- Published8 March 2011

- Published3 March 2011