Witness recalls Nazi Rudolf Hess landing in Scotland

- Published

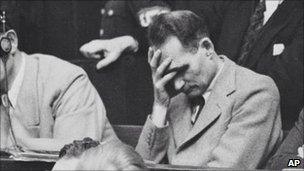

Hess was sentenced to life imprisonment at the Nuremberg trials in 1945

Exactly 70 years ago, one of the most bizarre episodes of World War II unfolded on a farm to the south of Glasgow.

On 10 May 1941, Adolf Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess parachuted into Scotland, landing in a field near Eaglesham.

The prominent Nazi had flown solo for nearly 1,000 miles from Bavaria in a Messerschmitt Bf 110, apparently on a peace mission in the days leading up to Germany's invasion of Russia.

He was promptly arrested by a pitchfork-wielding local farmer who took Hess to his farmhouse before alerting the authorities.

Another account tells of the war criminal being pulled from his wrecked plane and surrendering his luger pistol to members of the Corporal Royal Signals, based at Eaglesham House.

George McKenzie, from Rothesay, said his father Jack helped the airman out of the plane.

The 67-year-old explained: "He had surrended his pistol to my father and torch to another member of the guard.

"The prisoner was handed over to the Home Guard and the officer in charge of that unit was given the pistol."

Mr McKenzie added: "To date the Royal Signals involvement in this matter has been unrecognised possibly because they had no weapons, the guard had pickaxe handles and rubber truncheons, and they were responsible for alerting the anti aircraft defences of Glasgow, so their location would be classified information at the time."

And a few eyewitnesses to Hess' arrival are still alive.

John McVicar, 80, has memories of the day when the Nazi leader parachuted into Scotland.

He was 10 years old and living in Busby at the time, near to where Hess' plane went down.

Mr McVicar recalled the approach of Hess' plane shortly before it crashed.

He told BBC Scotland: "It was a Saturday. It was a very pleasant day - sun and cloud - and as I recall it my father and I were at the back of the house under a great big chestnut tree, kicking a football about, when we heard the unsynchronised engines of a German plane.

"Now that was unusual during daylight and it flew over the chestnut tree.

Jack McKenzie was said to have pulled Hess from the plane

"My father said: 'Look at him, look at him' but I missed him just as he went past.

"And then, strangely - I have never known the reason - we heard cannon fire.

"My father shouted: 'It is the RAF, they are after the bastard - they are after him'. But there was no RAF plane there.

"So my only explanation is that the plane was armed in some way and Hess was getting rid of the ammunition because obviously he was running out of fuel."

The reason Mr McVicar is able to recall seeing the plane in daylight, although it was late in the evening, is that the clocks were put forward by an extra hour during the war.

This meant that it got dark later than normal.

On the night Hess flew over, the sun set in the west of Scotland at about a 2215 Double Summer Time and the blackout came into force at about 2300.

Mr McVicar estimates Hess's plane was flying low - at between 1,000ft and 1,500ft - which seemed strange to him at the time because Hess bailed out.

"It was very, very unusual. We could see it wasn't a bomber and we recognised it as an ME 110 - it was recognisable to all of us in these days.

"So it seemed strange, but we didn't think about it. We just thought [the German pilot] had got lost."

Mr McVicar said less than an hour later, people started to gather at the Busby HQ of the Home Guard - now Busby Masonic Lodge - because they had heard Hess was being brought there.

He continued: "I and all the children gathered up there, waiting for him to be brought in. I got a bit fed up and went back to the park with my football to practice shooting in.

Press coverage

"In the interval, he was brought in, but my sister and brother were there and saw him being brought in.

"It is said that he had broken his ankle. That also seemed strange since I was told he walked in.

"About 20 minutes after that - I was going back and forward from the park - the press arrived.

"We expected a couple of reporters but there were more than that, so we thought: why is that? Perhaps it was just unusual that a plane came down in the middle of the day."

Mr McVicar said he walked back and forth in the two hours in which Hess was at Busby HQ, waiting for the German to emerge.

He said: "What I did see was the army arriving from Maryhill barracks.

Mr McVicar was playing football when Hess' plane flew overhead

"What struck me as strange was that it wasn't just a truck with a few soldiers. There were several officers, a couple of staff cars, which meant to me 'this is important'.

"I didn't understand what was going on but I knew there was something strange about it."

Mr McVicar said it was "quite civilised" when the Home Guard took charge of Hess.

"He was wearing his pilot's gear when he was taken there and he certainly was able to walk. If he had a broken ankle, it was well disguised."

Mr McVicar said villagers were "absolutely stunned" when the identity of the pilot emerged, although no-one could figure out why he had come to Scotland.

"The locals thought this was wonderful, what had happened to the village.

"It was a very exciting time for everyone - we were famous for a couple of days."

Negotiate peace

One engine from Hess' Messerschmitt Bf 110 is now on display in the National Museum of Flight in East Fortune, East Lothian.

Hess' reasons for flying to Scotland have never been fully explained, sparking countless conspiracy theories over the years.

But it seems he was attempting to reach the Duke of Hamilton, who he believed had sufficient political clout to help him negotiate peace with the United Kingdom.

As it turned out, Hess was arrested and later sentenced at the Nuremberg trials to life imprisonment. He died at Spandau prison in 1987.

Mr McVicar said at the time of Hess's landing in Scotland, local people came up with their own conclusions as to why Hess was there.

"When Russia was invaded [by Germany] in June 1941, we thought this must be the reason - Hess didn't want a war on two fronts. That was the conclusion we reached. We didn't think he was mad - we thought he was there with a purpose. That was how the civilians felt about it."

Mr McVicar doubts the whole truth about Hess's visit will ever emerge.

"It is one of those mysteries in history - I wish we did know," he added.

- Published23 March 2011