Study turns spotlight on Glasgow street gangs

- Published

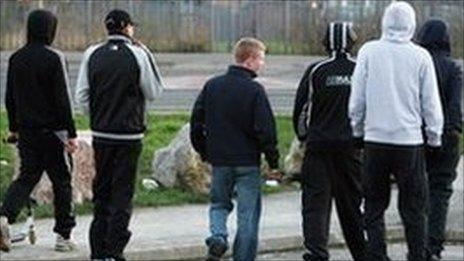

The research suggested gang members spent four to six hours each day on the street

Children in Glasgow can become socialised into gang culture from as young as 12, according to new research.

A study found the gangs were not hierarchical, organised criminal groups but friends that had grown up in the same area.

It suggested violence was an "accepted part of their lives".

The research looked at 60 members of 21 city gangs and was carried out by Johanne Miller from the University of the West of Scotland.

She spent weeks working with the participants as part of a PhD.

'Known enemy'

She said: "The process that emerged from participants was that young people aged between four and 12 began playing in the few streets that made up their scheme - a council-built estate - and began from a young age to be socialised into street culture.

"These children have grown up hearing stories of territorial rivals and the crimes they enact.

"So within the child's conscious there is a known enemy, an 'other' out there who is already a threat in their minds.

"They would begin absorbing street culture transmitted through story-telling and observations of older children in the area and family members.

"They would adopt the gang name, start using it and decide whether they wanted to fight or not. This is how they grew into the gang.

"This violence then becomes more serious for core members, and conflict becomes a central binding agent of the gang."

Ms Miller said gangs mostly occupied places such as derelict buildings and abandoned houses

Ms Miller said her research revealed that between the ages of 14 and 18, gang members spent four to six hours each day on the street, and longer at weekends.

They mostly occupied derelict buildings, parking lots, abandoned houses and factories and forests, with fighting taking place away from CCTV or regular police patrols, she added.

The research revealed a fight could start if a member entered another gang's territory and shouted their scheme's name.

"Territorialism is the conflict that creates tensions between other groups, and it separates and divides them from other young people and eventually traps them into their scheme through fear of reprisal," she added.

However, it was found that members drifted away from a gang after about three years, with every participant saying they wanted to progress to get a job and many expressing a "real fear" they would turn out to be worthless.

Ms Miller will talk about her research findings at the British Sociological Association's annual conference in Glasgow.

- Published13 August 2011