A modernist ruin and me

- Published

St Peter's Seminary opened in 1966 and was deconsecrated in 1980

This week saw one of Scotland's best known buildings brought back to life in a series of events. St Peter's College - originally designed in the 1960s as a Roman Catholic seminary - has been derelict for decades but a Scottish arts organisation hopes its sell-out shows will give it a new lease of life.

My own connections with the building - described by some as Scotland's modernist masterpiece - go back to the mid-80s.

I was still at school but writing articles for local newspapers when I went to do some interviews at a drug rehabilitation centre.

It was a strange place, a long walk up the hill from Cardross station, through the crumbling gate posts of an old country estate to what had clearly been the home of the family who ran it.

As I left, the priest in charge walked me back through the grounds and pointed to the huge concrete building which overshadowed the whole estate.

He asked if I wanted to look inside.

With a flick of some switches, a large empty room appeared from the darkness, stone staircases swirling above us. I discovered much later I was among the last people to view the still-intact seminary known as St Peter's College.

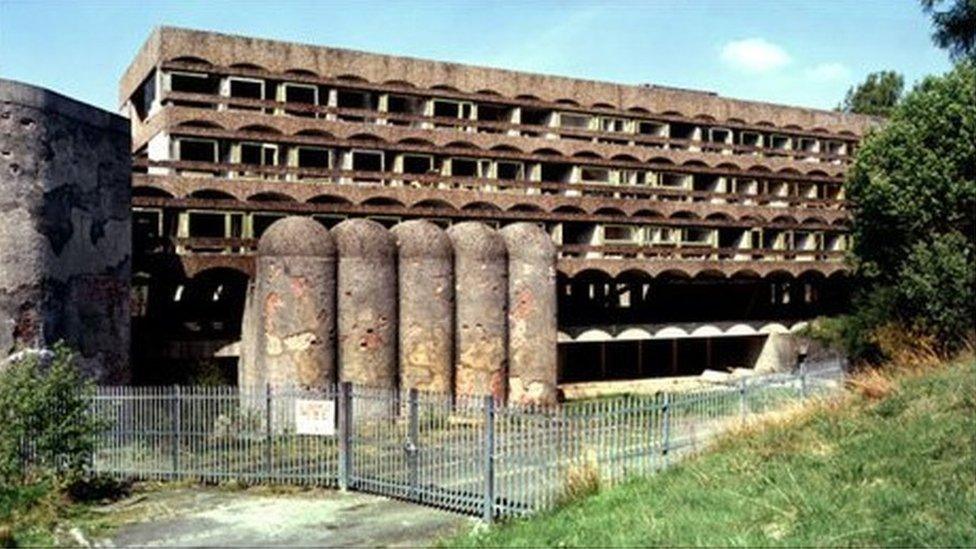

It was built in the 1960s by Andy Macmillan and Isi Metzstein for the Scottish firm Gillespie, Kidd and Coia.

Inspired by Scottish tower houses as much as the French architect Le Corbusier, it was intended to wrap around the existing old house and family estate - a religious campus as much as one building.

Archive from the time shows priests descending the stone-ramped staircases into the main chapel, an elegant procession which perhaps didn't match the reality.

Monsignor Peter Smith was a seminarian in the 70s.

He recalls draughty common rooms and bleak bedrooms. Stone cold, even in the height of summer, with little to break up the grey.

The building is now category A-listed. But modernist masterpiece or not, it didn't last.

St Peter's never reached capacity and just over a decade later, it closed down.

With the number of vocations falling, priests were trained in other facilities. Alternative uses were considered - a hotel, houses, an art centre - all proved unviable.

Kilmahew House, where that rehabilitation centre had been, burned down in 1995.

The rest of the site fell further into disrepair.

Vandals and the elements took their toll.

The site, deconsecrated in 1980, was barely recognisable, sealed off for safety, although architecture devotees found a way through the fence when they made pilgrimages there.

Artists, writers, filmmakers were all inspired by the story of the great Scottish building, now lost.

Its architects spoke with sadness about the loss of the building and the accolades which came too late to save it.

It won them a gold medal from the Royal Institute of British architects. More recently a sadder accolade - as one of the World Monument Fund's most endangered cultural landmarks.

As the decades passed, there was an acceptance that there was too little left to restore and rebuild. We mourned the passing of each of the architects, and it seemed their greatest work too.

And then 10 years ago, a different approach from the environmental arts organisation NVA.

Its determined director Angus Farquar said "what if instead of rebuilding, we approached in the same way as an ancient castle or cathedral?".

He proposed a modern ruin, where the building lives on - through interpretation of the space, music, light and imagination.

It still required money, to consolidate and make safe the ruined building, and commission those who would interpret it.

But this week, we saw the first fruits of that idea.

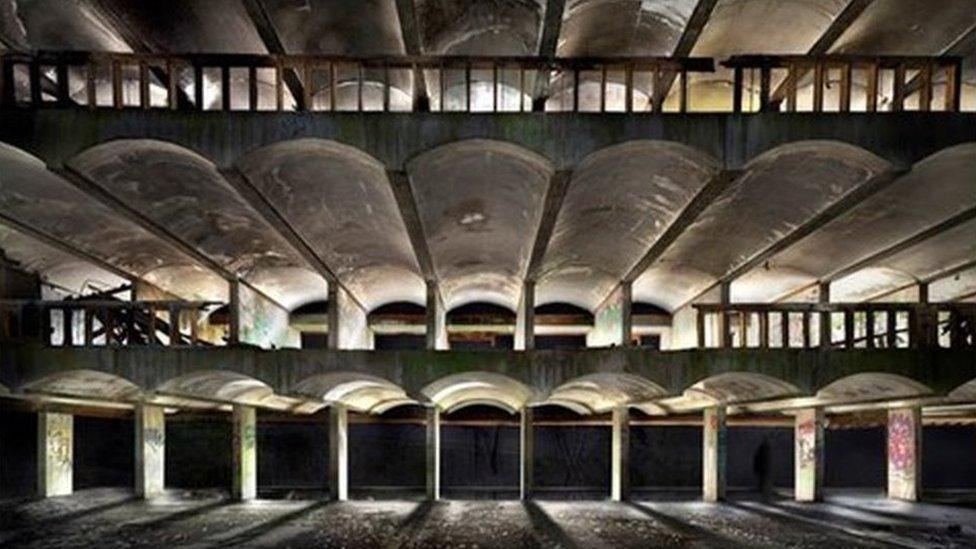

The first thing that's apparent is that the building has been cleared.

No piles of debris, ragged ceilings and gaping floors.

It is possible to walk around the space and imagine what its architects intended.

Little details which point to Charles Rennie Mackintosh or Frank Lloyd Wright.

The light still pours in, although the glass is long gone, nature poking and prodding its way through gaping window frames.

The graffiti remains - now a vibrant part of the building's look.

Audiences are promised a "subtle composition of lighting, projection and choral music"

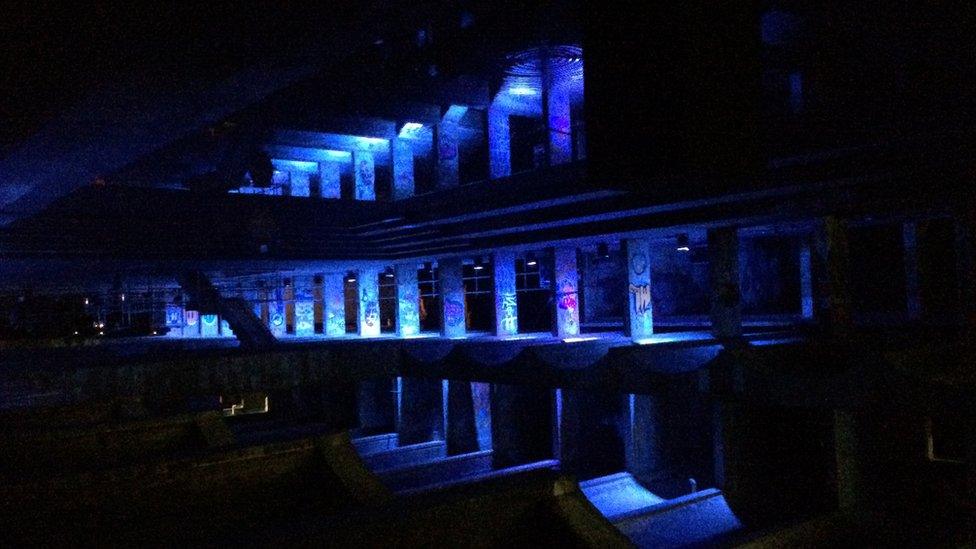

As darkness falls, bit by bit, the building is illuminated to an eerie soundtrack of choral music.

A giant thurible swings across a pond, created from the sunken floor of the old refectory.

The first of 7,500 visitors watch as it sprays incense into the air around us.

An eerie soundtrack, created by composer Rory Boyle and sung by the University of St Andrews Music Centre and St Salvator's Chapel Choir.

The whole site is alive again. Foodstuff is being grown in the once overgrown walled garden, more and more people are joining locals to once again walk through the estate.

And the towering concrete building no longer looks like an aberration - a concrete blot on the landscape - but a building once again alive with people, with ideas, and with inspiration.

NVA are hopeful that this 10-day event - the opening gambit of the festival of architecture - will secure the funding they need to make this a permanent landmark, a place to wander on a sunny afternoon, to think, to imagine, just as you would around any much older ruin.

And after 30 years of wondering what would become of the sad shell of St Peter's College, I hope with Hinterland it has a chance of a happier ending.

- Published18 March 2016