Dali helps scientists crack our brain code

- Published

Researchers wanted to know how the brain processes information

Scientists at Glasgow University have established a world first by cracking the communication code of our brains.

Pioneering research in the field of cognitive neuroimaging has revealed how brains process what we see.

The work has been led by Prof Philippe Schyns, the head of Glasgow's school of psychology, with more than a little help from Voltaire and Salvador Dali.

How Dali's mind worked is a matter of continuing conjecture. But one of his works has helped unlock how our minds work. Or more precisely, how our brains see.

Prof Schyns, who is also Director of the Institute of Neuroscience and Psychology, explains: "Our main interest was to study how the brain works as an information processing machine, external.

"Typically we observe brain signals but it is quite difficult to know what they do.

"Do they code information from the visual world - do they not? If so, how?

"Do they send information from one region of the brain to another region of the brain? If so, how?"

Which is where Salvador Dali comes in. And for that matter Voltaire.

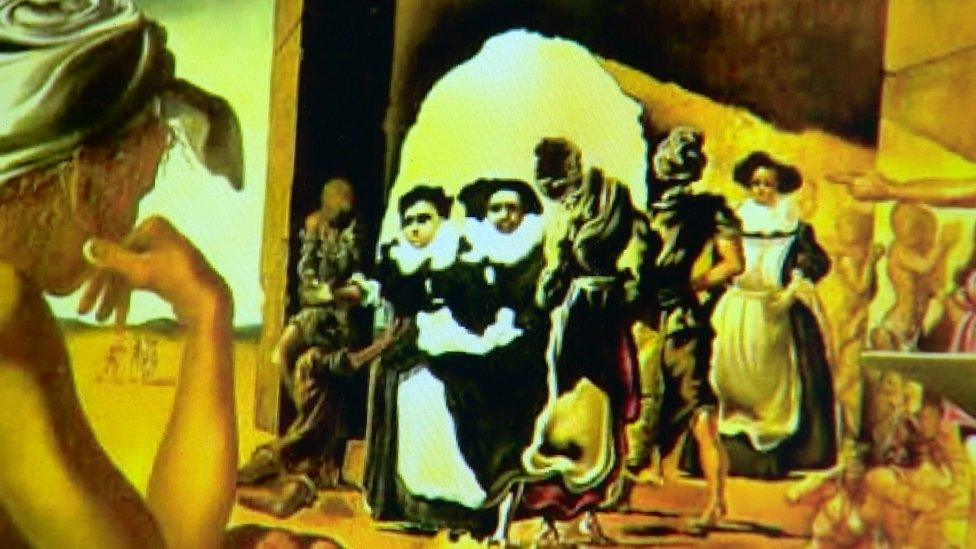

In 1940, Dali completed his painting "Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire".

And there at the heart of the image is Voltaire. Or is it?

His bust is what some people see. Others see Voltaire's "eyes" as the heads of two figures - usually a pair of nuns.

By asking test subjects which image they saw, researchers were able to map how the brains processed the information

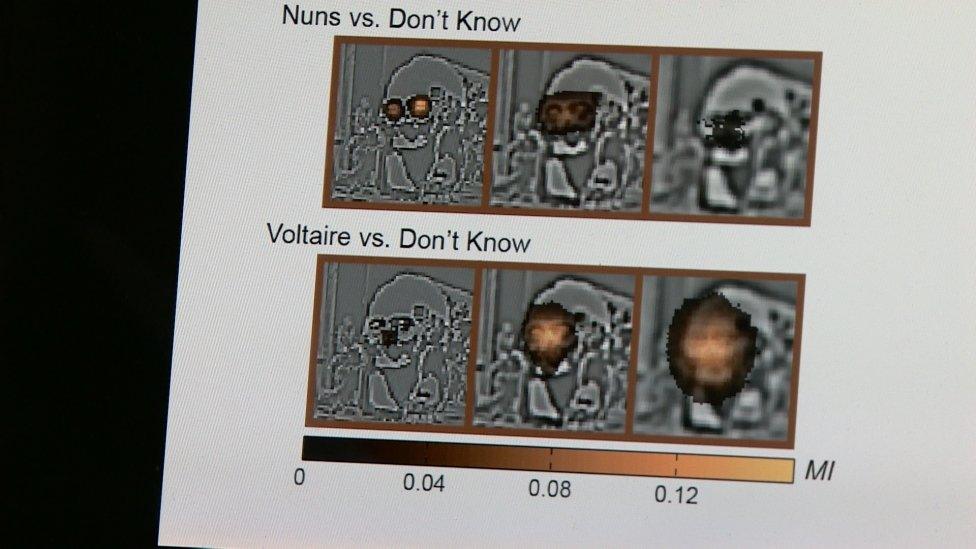

This visual ambiguity was of course Dali's intention. But by asking test subjects which image they saw - or neither - the researchers were able to map how the brains processed the information.

As expected, the right side of the brain handled the left side of the image and vice versa.

But Prof Schyns says the research revealed much greater detail: "We found very early on, after around 100 milliseconds of processing post-stimulus, that the brain processes very specific features such as the left eye, the right eye, the corner of the nose, the corner of the mouth.

"But then subsequent to this, at about 200 milliseconds {...} we also found that the brain transfers features across the two hemispheres in order to construct a full representation of the stimulus."

Cracking the brain's code

Tracking how our eyes communicate with our brain, and then how our brain sends signals to itself, is the result of 15 years' work by Prof Schyns and his colleagues. It has been funded by backers including the Wellcome Trust.

And there's a lot more.

A compelling analogy is with Bletchley Park. The wartime allies were able to monitor Nazi radio traffic, but it took the work of Alan Turing and his colleagues at Bletchley to crack the code and find out what the signals actually meant.

The 21st Century Glasgow researchers have similarly cracked the brain's code, revealing the algorithms the brain uses to send and process information.

So is Glasgow University the Bletchley Park for the brain? It's an analogy with which Prof Schyns is comfortable.

"Prior to this research people would know that two brain regions communicate - as the allies knew the Germans were doing in World War Two.

"But prior to the enigma of Turing people did not know what they were communicating about."

Now with the brain, as with the Enigma codes, we are able to track with precision where, when and how information is processed.

Prof Schyns says there are many possible applications: in fundamental brain research, in dealing with conditions like stroke in which brain processes are disrupted, and perhaps in helping new generations of robots see the world in the same way we do.

Inevitably, though, more research is required.

We may have cracked the code and tracked the images to the area where they are processed.

But how do our brains then decide whether that is Voltaire - or two nuns? We don't yet know.

Indeed some people think one of the nuns has a beard, so maybe they're two Dutch merchants.

Whatever you think, it's your decision. But science is getting closer than ever to working out how you made it.