Russell's in Brussels

- Published

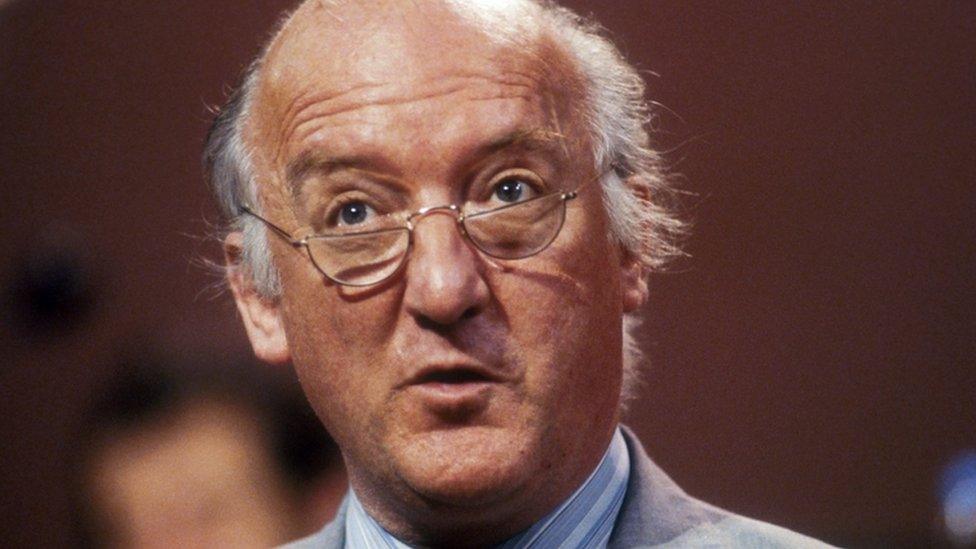

Russell Johnston was frequently to be found in Brussels

Anyone remember Russell Johnston? Well, of course you do. He led the Scottish Liberals for fourteen years, he was a fine orator and a noted intellectual, leavened with a neat line in mischievous wit.

I recall, in particular, the occasion when a Scottish Liberal conference was embroiled in a decidedly tricky debate. Russell, in the chair, brought matters to a convenient close by declaring that the weather was worsening and the last ferry of the day was about to leave.

Was that, I asked him later, strictly true? "Nearly," he replied, with a typically glorious grin.

But, in addition to being a Scottish party leader and a Highland MP, Russell looked outwards. He sustained a passionate interest in European politics and served on sundry European bodies for decades, including the Assembly which was the predecessor of the directly elected European Parliament.

Indeed, such was that passion that the statement "Russell's in Brussels" became a catchphrase in Liberal circles.

Sometimes it was deployed in admiration for his commitment to the cause of European co-operation. Sometimes, frankly, it featured a tiny note of irritation. Europe? Again? Really?

The phrase "Russell's in Brussels" sprang to my mind as I contemplated the latest machinations over Brexit. That is because, yesterday, it was true once more.

Russell was indeed in Brussels. Mike Russell, that is. The Cabinet Secretary for Mitigating Brexit was in the European capital in search of common ground.

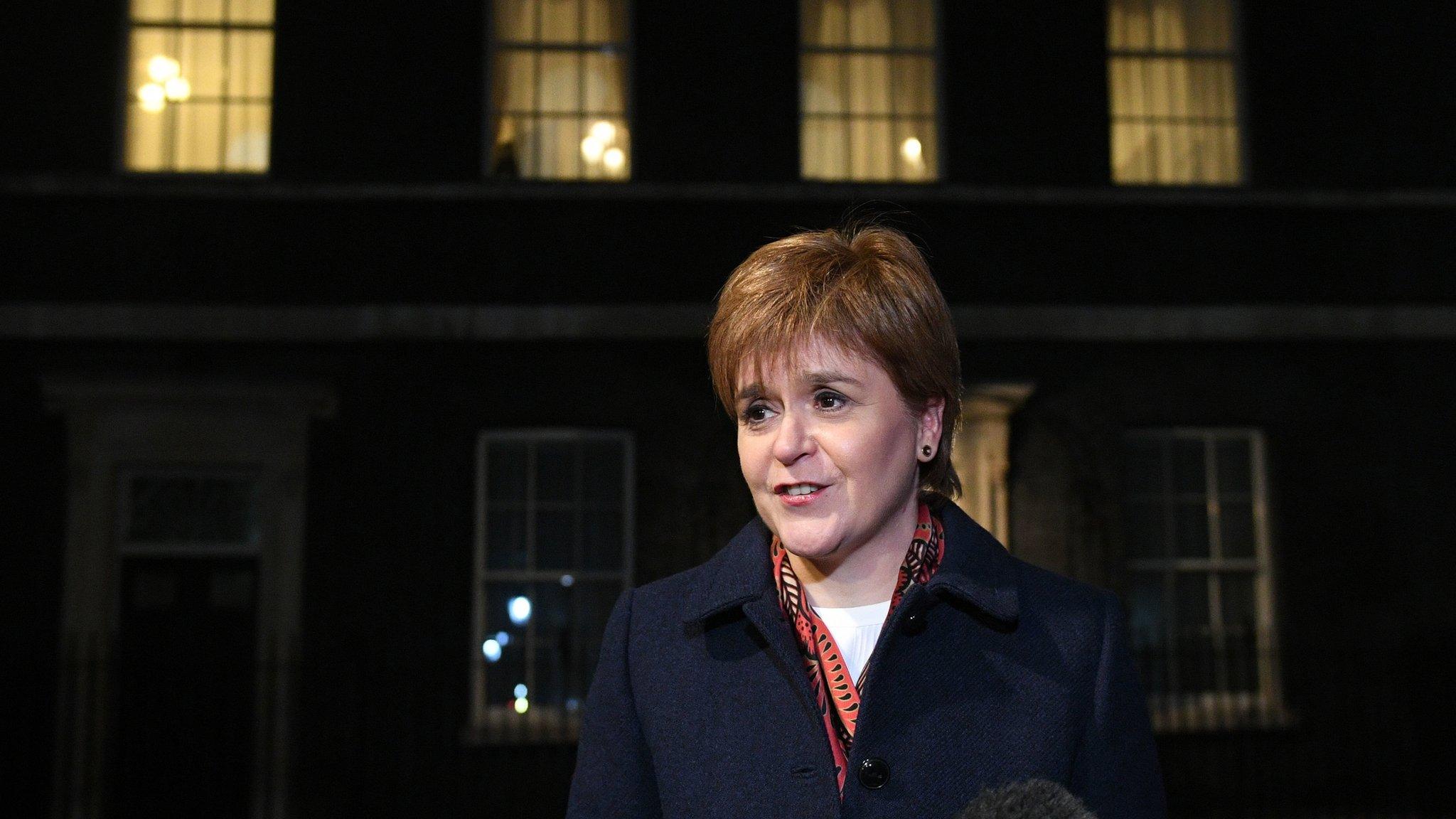

Another Russell - Mike, this time - has been in Brussels for Brexit talks

Today he is set to join Nicola Sturgeon and the Welsh first minister in the latest round of talks with the prime minister in London.

Downing Street say these talks with devolved administrations deliver on a promise made by Theresa May in her Commons statement. The most recent one, that is. There have been a few.

The Scottish government has voiced discontent that a meeting scheduled for Thursday has been cancelled. The JMC (EN) - Joint Ministerial Committee on European Negotiations - had been due to review progress on said EN.

Not a lot, since you ask. But the JMC mechanism was specifically designed to allow the devolved administrations a degree of - arguably limited - scrutiny over the handling of these talks. So why cancel?

With discernible weariness, Downing Street argues that the JMC chat has been overtaken by today's talks at a notably higher level.

But, say the Scottish government, it is scarcely a good start to the project of involving Scotland and Wales to cancel a meeting in which they have a formal role. Ah but, say Downing Street…..and there let us draw a temporary veil.

Low expectations

The wider issues are the extent to which Scotland is genuinely being consulted - and, of course, whether the broader efforts, with or without Scotland's help, are getting anywhere.

Nicola Sturgeon told me in advance that she was scarcely imbued with high expectations in advance of the talks. She said that the PM had shown a stubborn reluctance to shift ground, despite the evidence that her present position had been rejected.

The FM told me, further, that she would remind Theresa May that Scotland voted to remain in the EU and that the "option of independence" remained in play. Was, indeed, becoming more salient by the day.

All of which, once more, raises more fundamental topics. Let us try to sift those a little. Russell Johnston would have approved.

Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon previously held talks at Downing Street in November

Firstly, there is a continuing controversy over delivering upon the result of the Brexit referendum. At various points, various voices can be heard declaring, with variable degrees of passion: "That isn't what the people of Britain / Scotland / Scunthorpe voted for."

Such speakers generally deploy that statement when they are seeking to dingy some particular aspect of Brexit. Indeed, it is remarkable how frequently the true views of the people are contrived to coincide with an individual obsession of the speaker.

Membership of the customs union? The people didn't vote for that. Membership of the single market? The people didn't… The restoration of the European Cup Winners Cup? The people…

I must confess I find this a mite exasperating. It is impossible, frankly, to be precise about what folk voted for. No detailed or indicative programme was placed before the electorate in the 2016 referendum.

It was Remain or Leave. There was, as you will recall, a narrow majority for Leave.

Difficult negotiations

At least in the 2014 independence referendum, there was a detailed Scottish government White Paper. However, even then, it would be wrong to infer that every single page of that document featured in the choice.

Had there been a Yes vote, that would have been followed by detailed, probably difficult, negotiations between Edinburgh and London, producing an outcome which would not have reflected the entirety of the advance paper.

Hence the worry, in some Nationalist quarters, that a further Brexit referendum might set a precedent for independence.

But at least there was a document. There was a detailed set of proposals. Debate could and did resound around the topics raised in that document.

With Brexit, the debate was generic, rather than precise. Optimistic promises were made on both sides. Remember the forecast that a free trade deal with the EU post Brexit would be "one of the easiest in human history".

What motivated people to tick one box or the other?

So it is impossible to say, precisely and in detail, what the Brexit popular vote mandated. Folk opted, just, for Leave. Beyond that, the details are down to the elected politicians and government who occasioned that referendum in the first place.

Now, it is argued that Theresa May has brought trouble upon herself by insisting upon a series of red lines, such as abandoning any thought of the customs union, single market or freedom of movement.

She, it would seem, takes her guidance from divisions within the Conservative Party - the genesis of the referendum in the first place - and from taking the popular temperature during and since the referendum.

For example, she discerns popular disquiet with the issue of immigration - and promises to curb freedom of movement as a consequence, thus ruling out single market membership.

But, to be clear, she is not precisely mandated to do that or indeed anything else. We come back to what can be reasonably steered through the House of Commons - after negotiations with the EU - in order to satisfy the generic demand to Leave.

Red lines

And those red lines? They were excoriated again on the wireless today by Alyn Smith MEP, a thoughtful and occasionally acerbic analyst of these troubled times.

Mr Smith made his points well, as is his custom. But it struck me that, to some extent, he exculpated the EU a little too readily.

Were there not red lines emanating from Brussels too? Most notably, on the Irish backstop.

Now, it may be argued that the backstop simply fulfils a promise to a remaining EU member, the Republic of Ireland, and protects the Belfast / Good Friday Agreement which the EU, among many others, regard as vital for peace.

But Mrs May might make similar pleas for her red lines. Whatever its origins, the insistence upon a backstop has caused decidedly serious problems for the passage of the deal in the Commons.

At which point there arises the search for solutions to that backstop topic. One hears the notion that it might be time-limited. Irish politicians, understandably from their perspective, say that a backstop with a deadline is no such thing. It provides no sustainable guarantee at all.

Might it be possible to find a formulation which says that the objective is a trade deal, that the backstop is not desired and, in any case, ends after five years - unless all sides agree that it should be continued pro tem?

Nicola Sturgeon was pictured signing her 2017 letter to Theresa May, calling for a second independence referendum

Then there is the related topic of independence. Nicola Sturgeon says she will raise the subject with the PM today - although Ms Sturgeon also adds, wryly, that she suspects Mrs May is already rather well appraised of the SNP's standpoint.

But is Ms Sturgeon about to make a move? Is she about to demand, once again, a Section 30 Order to transfer the power to Holyrood to hold a further referendum on Scottish independence?

Remember the history here. Westminster has control over the constitution under the Scotland Act 1998 which founded devolution.

A Section 30 order permits an additional power to be transferred, temporarily, to Holyrood in order to facilitate an agreed project. Just such an order was granted, by agreement, to enable the independence referendum in 2014 to take place.

Ms Sturgeon is very well aware of that. She did much of the detailed negotiation with the then Secretary of State Michael Moore in advance of the Edinburgh agreement signed by David Cameron and Alex Salmond.

On the 31st of March 2017, now as FM, Nicola Sturgeon wrote to the prime minister urging the instigation of further Section 30 talks. She later halted this process, saying she would return to the topic when there was clarity over Brexit.

That return is the moment we now await. Today, at Holyrood, there is an intriguing question tabled by Mike Rumbles of the Liberal Democrats.

Mr Rumbles, who frequently combines sagacity with mischief, is seeking to learn the Lord Advocate's view on whether the Scottish Government would have the competence to hold indyref2 - without a further Section 30 order.

I await the legal verdict eagerly. But I suspect Mr Rumbles already knows the political answer. Nicola Sturgeon's government would not sanction such a plebiscite.

They would regard it as unconstitutional, contrary to the strategy which the SNP has deployed of seeking to build independence from working to gain popular acquiescence, within the constraints of existing statute.

Theresa May in 2017: "We should be working together, not pulling apart"

Further, they would fear that a referendum without UK sanction would be boycotted by unionists, arguably undermining the outcome. Further still, they worry that any such ballot - and its outcome - would fail to win international recognition.

Including from the EU, whose institutions have said repeatedly that such matters require to be settled, constitutionally, within the structures of the member state, the United Kingdom.

Still, Ms Sturgeon will have noted the degree of disquiet within Nationalist ranks. The demands for action, not least from her immediate predecessor.

It is important not to over-state this. I do not believe that the SNP is in an incipient state of insurrection against its leader over its main focus, independence. There is a recognition of the difficulty confronting Ms Sturgeon.

But there is some impatience. There is discontent. It remains feasible that Ms Sturgeon will address the issue by restating her request for a Section 30 transfer.

Would the PM grant that instantly? It seems not. In the Commons today, she said that the UK should be "pulling together, not being driven apart". A phrase she has used before, suggesting that the question from a Scots Tory backbencher did not come as a surprise to her.

In which case, say senior Nationalists, the PM's refusal would become a topic of debate and strategic campaigning up to and perhaps through the next Holyrood election.

However, just as we cannot be precise about the past verdict of the British people over the EU, we cannot be precise as to when the Scottish people may be consulted once more about their own future within the UK.

- Published23 January 2019