Bandstands: The industry built on Victorian social engineering

- Published

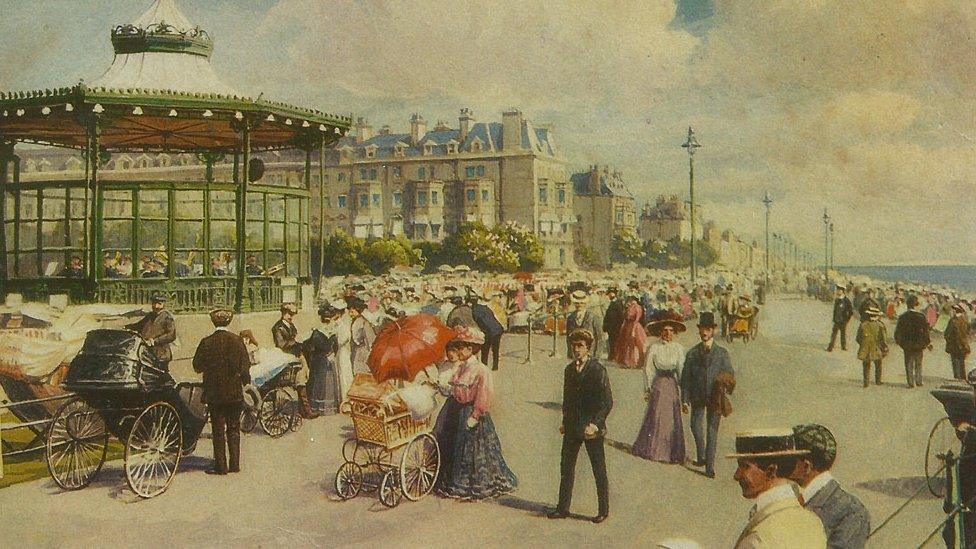

The Leas bandstand on Folkestone seafront was made by the James Allan Elmbank Foundry and erected in 1895.

Victorian bandstands remain a popular feature in many parks and open spaces across the UK. But why were so many of them built in Scotland?

Many of the more influential Victorians had worries about the working class.

With what little leisure time they had, those employed in the mines and factories might drink alcohol, or worse.

What was needed was something more improving.

Louise Carnegie, the wife of the industrialist Andrew Carnegie, gifted a bandstand from the Saracen Foundry to the people of Dunfermline. This image dates from her visit in 1887.

And, according to historian Paul Rabbitts, bandstands were a very public part of this commitment to uplifting activity.

"Their purpose was part of what they called 'ordered, rational recreation'," says Paul.

"It was really something to get the working classes - to get them into parks and open spaces, and give them something that was much more ordered and regulated leisure and recreation.

"Basically it was to get them out of the gin palaces and the pubs.

"They saw music as being part of that, and the bandstands came out of that."

Many bandstands, such as this one in the centre of Chester, are still in regular use.

This attempt at social engineering created an economic legacy, with workshops in the central belt of Scotland making many of the bandstands erected across the UK and beyond.

This 1896 Saracen bandstand was erected in Worthing seafront. It is one of many which have disappeared completely.

Dun Laoghaire in Dublin still has this fine example of a Walter MacFarlane bandstand.

"It was all to do with the kind of ore that was found in the hills just outside Glasgow," Paul says.

"The ore there was perfect for smelting and casting of iron. So what you found was you had a whole industry grow up in and around Glasgow.

"One of the very earliest foundries was Carron Ironworks near Falkirk but the biggest manufacturer of all was Walter MacFarlane and the Saracen Foundry in Possilpark in Glasgow.

"They literally cornered the market."

One of the many Saracen bandstands survives on the esplanade at Bognor Regis.

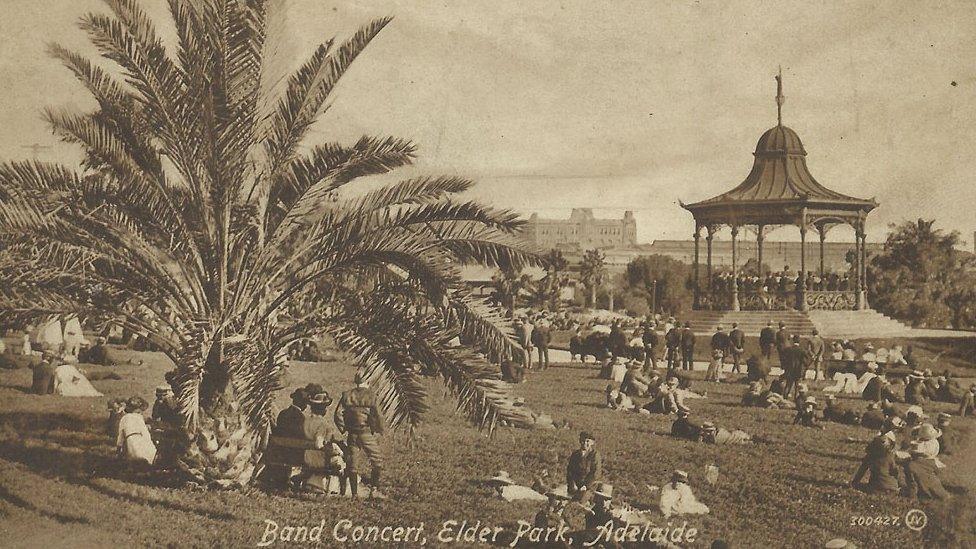

Bandstands from Walter MacFarlane's works were exported around the world. This one is in Elder Park in Adelaide, South Australia.

Some of the bandstands, such as here at Hexham in Northumberland, can be lit at night.

Bandstands retained their original purpose for decades, attracting crowds who might otherwise waste their time. This one by the Lion Foundry in Kirkintilloch was in Elder Park in Govan.

Paul says MacFarlane was "a very clever man".

"What he did was that he was very good at marketing.

"So nowadays we take for granted the internet, and catalogues and that kind of stuff.

"He used advertising through published catalogues that showed bandstands and all the other kind of things that they cast as well.

"He marketed them nationally but also worldwide as well."

Walter MacFarlane gave us one of the most photographed bandstands in the world, at Brighton in East Sussex.

For many years Corporation Park in Blackburn featured a bandstand by the Lion Foundry in Kirkintilloch.

The bandstand at Clapham Common in the London Borough of Lambeth dates from 1890 and was restored in 2006.

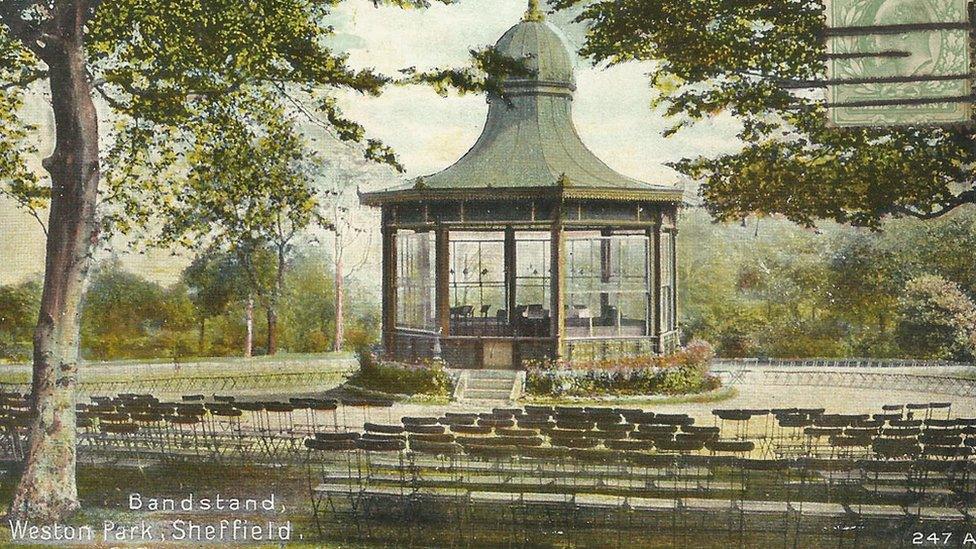

So loved were bandstands that they often featured in postcards. This Elmbank Foundry structure in Sheffield's Weston Park dates from 1875 and has recently been restored.

The bandstand in Shrewsbury dates from 1887 and has been extensively restored. It was made at the Milton Ironworks in Glasgow.

Recent years have seen a renaissance in Britain's bandstands, with many being restored or rebuilt using lottery funding.

Some, such as the one at Wilton Lodge Park in Hawick, had gone almost without trace.

Paul says: "All that was left was the remnants of the plinth, which became a flowerbed and then a fishpond and then an empty piece of open space.

"They got lottery money and put back a replica of the original Scottish bandstand back in there."

The bandstand at Wilton Lodge Park in Hawick is one of more than 100 brought back to life with lottery funding.

All images are subject to copyright.