Should Greenock's 'Sugar Shed' become Scotland's museum of slavery?

- Published

Ships and sugar were for 250 years the foundations of Greenock's prosperity. But another word starting with S is also intertwined with the town's fortunes.

One MSP thinks a new national museum acknowledging Scotland's historical links with slavery should be created there. But why Greenock?

The Triangular Trade

In the 18th and 19th Centuries Greenock and nearby Port Glasgow were Scotland's gateway to a lucrative in trade in sugar, tobacco, rum - and sometimes humans.

As in Glasgow, those links are still reflected in street names - Tobago Street, Jamaica Street, Antigua Street, Virginia Street.

Fortunes were made and the merchants enjoyed years of prosperity but it came at a terrible price.

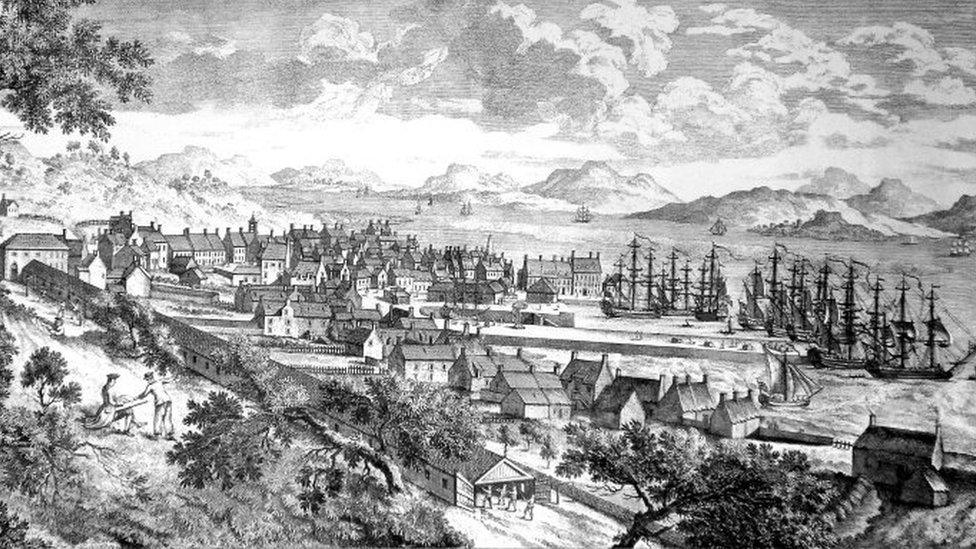

This engraving from the 1760s shows the tobacco ships docked at Port Glasgow

Slavery existed in Africa before the Europeans came but the colonisation of the Caribbean islands opened up a dark new chapter.

When, in 1562, the English sailor Captain John Hawkins captured 300 Africans and sold them in the "Americas" he made so much money others were quick to follow.

At first the London-based Royal African Company had a monopoly on this sinister cargo but other cities, notably Bristol and Liverpool, lobbied successfully to get involved.

Then, in 1707, the Act of Union paved the way for Scottish ships to join what became known as The Triangular Trade.

The first stage of the voyage took them to West Africa, carrying goods such as glass, textiles, metal or guns that could be exchanged for captured Africans.

All along the coast were "slave forts" where captives - taken there usually by African middle-men - were stripped and chained, ready to be traded.

Slave forts like this one in Senegal made it easy for ships to pick up their human cargo

The next stage of the journey - the middle passage - was brutal for the human cargo, crammed into tiny spaces in the hold for months, sometimes beaten, branded or sexually abused by the crew. According to some estimates a fifth of slaves died at sea, many taking their own lives in despair.

There were profits to be made on each side of the triangle. In the 18th Century a "strong and able" slave could sell for more than £100 - that's £11,000 in today's money. Young women were valued because they could produce more slaves.

The final leg of the journey saw the ships return to Scotland laden with more high profit goods such as sugar, rum and tobacco.

You may also be interested in:

While the numbers of Scottish slave ships officially recorded as sailing from Greenock and Port Glasgow are small by comparison with Liverpool or Bristol, Scots were involved in other ways.

A fifth of masters on slaving voyages from Liverpool are believed to have been Scottish and Scots played a prominent role in many England-based slaving enterprises.

On Bunce Island, a fortified outpost at the mouth of the Sierra Leone River, a visitor in the 1770s described white men playing golf attended by African caddies in tartan loincloths.

The plantations were also seen as places to become rich, enticing thousands of Scots to the Caribbean in an attempt to make their fortune.

By the early 19th Century a third of the plantations in Trinidad, the world's largest sugar producer, are believed to have been Scottish-owned.

The profits to be had from transporting slaves were soon dwarfed by the riches flowing from the commodities they produced.

Proximity to the North Atlantic Trade Winds gave Scottish ships a huge advantage when it came to fetching tobacco from Virginia's plantations.

Before the Clyde was deepened, allowing big ships into the heart of Glasgow itself, Port Glasgow grew into one of the world's busiest tobacco ports.

James Watt - a reputation under the spotlight

Greenock's most famous son is James Watt, whose improved steam engine was a defining development of the Industrial Revolution.

But in recent years, the reputation of Scotland's best known engineer has been re-examined, with some historians suggesting the Watt family both benefited from and participated in the trade in humans.

James Watt is revered as the inventor of the modern steam engine, but his family benefited from trading goods produced by slavery

Two years ago a report from Glasgow University, external - which has an engineering school named after James Watt - described the inventor's father as a "West India merchant and slave trader who supported Watt in his career".

Caribbean planters were also significant consumers of Watt's steam engines, using them to extract more juice from the sugar cane.

In 1791 Watt cancelled an order for a steam engine from a French company in what is now Haiti, describing the transatlantic slave trade as "disgraceful to humanity", and arguing for its gradual abolition through "prudent" measures.

But as a younger man - before the anti-slavery movement gathered momentum - there is evidence Watt was himself involved in bringing a young boy named Frederick, probably a slave, from the Caribbean to Greenock, on his way to serve in a country house in Moray.

What is certain is that Watt's family, like thousands of others throughout Scotland, profited handsomely from the trade in goods produced by slaves.

The Sugar Shed

Slavery was abolished in the British Empire years before Greenock's first commercial sugar refinery was established in 1850.

But the legacy of slavery endured, the descendants of slaves providing the cheap labour for imports.

In Virginia more than 500,000 people were still enslaved but American independence had put the brakes on the tobacco trade.

Sugar, though, was a growing business opportunity. Within two decades Greenock had 14 refineries, with 400 ships a year arriving from the Caribbean.

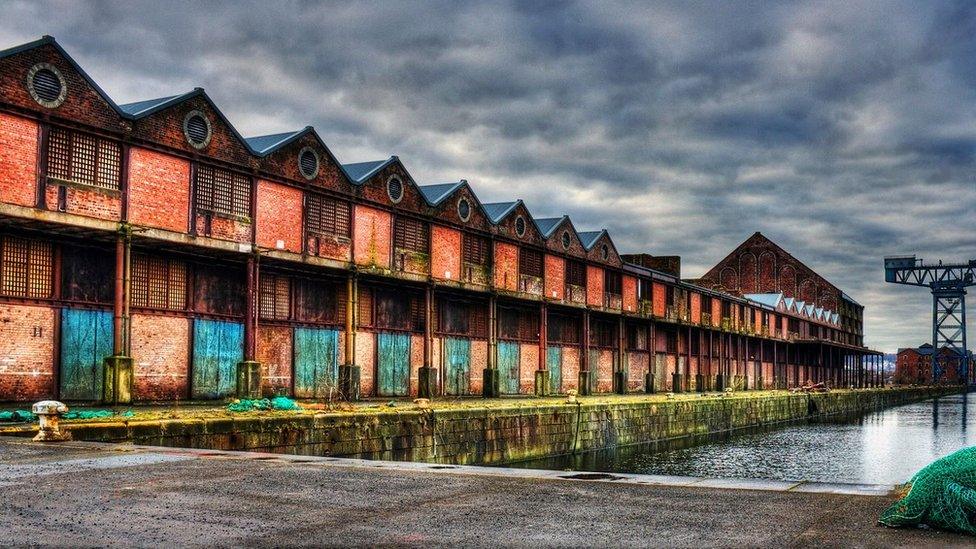

The A-listed Sugar Shed, a cavernous warehouse now standing empty beside Greenock's James Watt Dock, is a dilapidated monument to the trade that sprang from the labour of plantation workers.

Greenock's "Sugar Shed" has been suggested as the site for a museum chronicling Scotland's relationship with slavery

MSP for Greenock and Inverclyde Stuart McMillan thinks the Black Lives Matter movement underlines the need to "own our past".

He argues the Sugar Shed is the ideal location for a national "museum of human rights", highlighting not just slavery but also other historical injustices such as the Highland Clearances.

"Greenock was the departure point for more than 600,000 people leaving to go to the New World," he explained.

"In terms of the Highland Clearances, many folk left the Highlands and came and settled in this part of Scotland... very few people know about the Highland Clearances but that's a bit of the story that could also be told."

A waterfront redevelopment incorporating a museum like that seen in Dundee, he says, could help reinvigorate an area which nowadays has some of the highest deprivation levels in the country.

But the idea of bringing together the Highland Clearances and chattel slavery - where humans were legally owned as property - in one institution has its critics.

Fellow SNP politician, Glasgow councillor Graham Campbell, thinks such "massive historical events" deserve their own dedicated museums and shouldn't be "clubbed together".

He suggests a multi-site museum model, like the Tate or the V&A which operates in both London and Dundee - but with Glasgow at the centre.

"The epicentre has to be in Glasgow because this was the main city which benefited from it," he argues.

While Black Lives Matter has given impetus to longstanding calls for such a museum, the coronavirus pandemic has thrown up new obstacles, with many of Scotland's museums facing financial challenges.

But the UK currently has only dedicated slavery museum - the International Slavery Museum, external in Liverpool - and while possible locations may be debated, campaigners are united in the conviction that this aspect of Scotland's history needs greater recognition.

"This is a part of Scotland's story that needs to be told," says Stuart McMillan.