'Boring' research reveals what lies beneath Glasgow

- Published

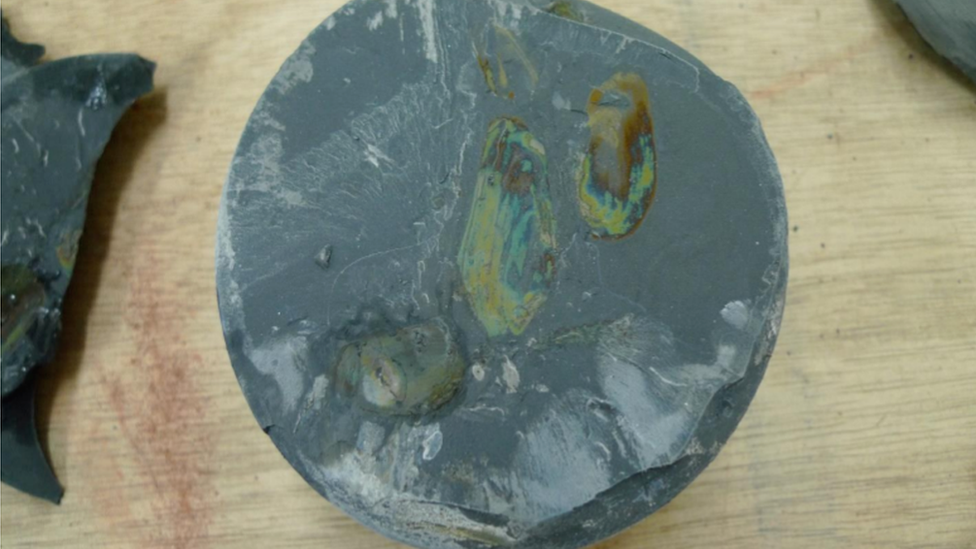

Mussels preserved as fossils have been found nearly 200 metres below the surface

Boreholes drilled deep beneath Glasgow are revealing the secrets of the rocks on which the city stands.

It is part of a project aiming to find out more about how warm water moves in abandoned, flooded mine workings.

The big idea is to harvest the energy stored beneath the east end of the city and Rutherglen as a source of renewable heat for homes and industry.

It is centred on an observatory that studiously avoids looking at the heavens.

The UK Geoenergy Observatory in Glasgow is looking in the opposite direction - up to 199 metres below the city's surface.

Preserved as fossils

It is using a network of 12 boreholes which have been fitted with more than 300 sensors to measure the chemical, physical and microbiological properties of the subsurface environment.

Now the observatory, run by the British Geological Survey, has released data and images revealing the world up to 199 metres below the city's streets.

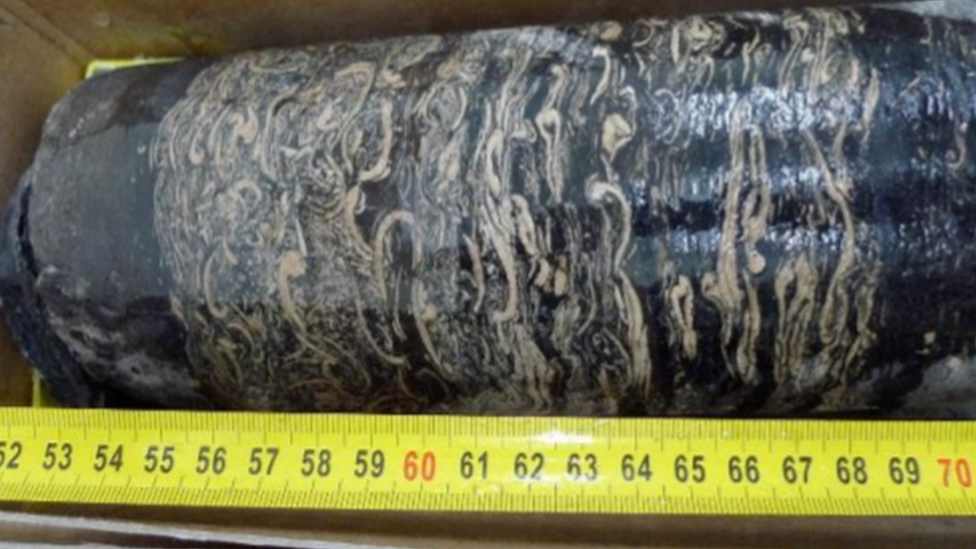

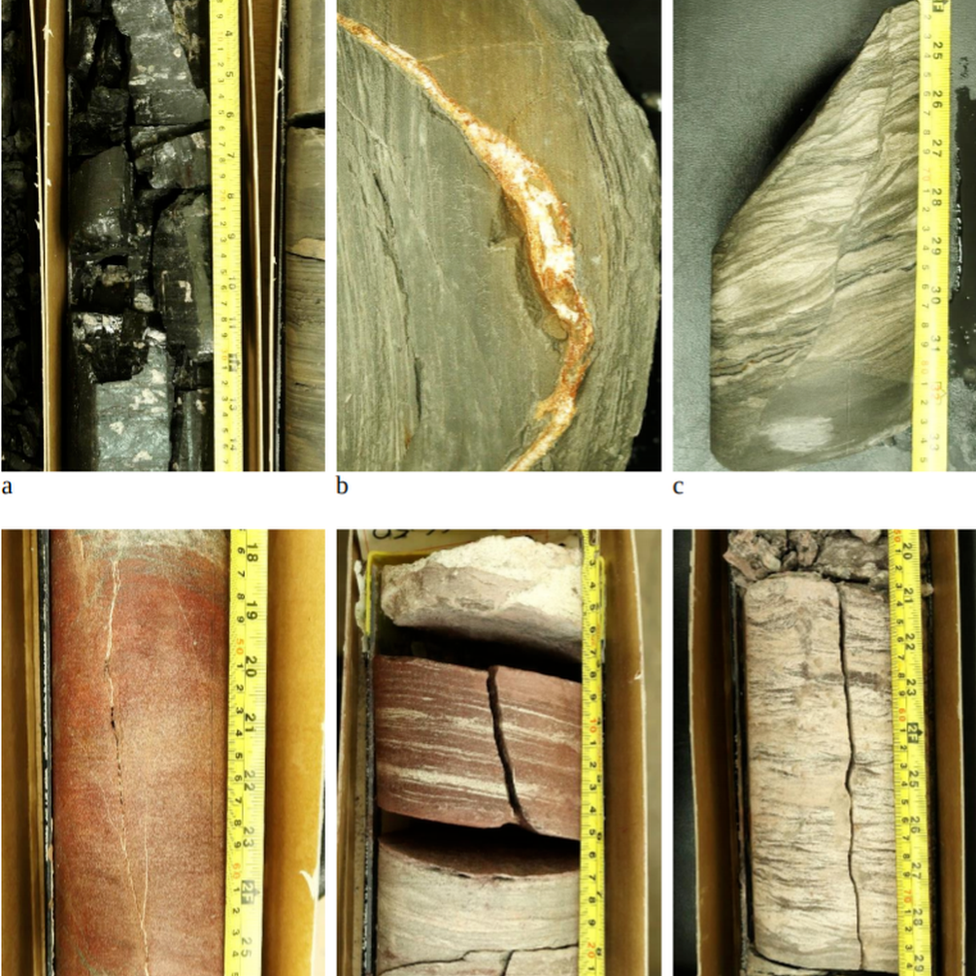

The cores of the boreholes have been subjected to high-resolution scanning to show some things Glaswegians might not expect.

Among them, mussels.

The molluscs have been compressed over a period of up to 300 million years

These molluscs are far from fresh. In fact, they were last alive alive-oh (to quote the song Molly Malone) around 300 million years ago and are preserved as fossils.

Palaeontology is not the primary purpose of the Glasgow project and its sister sites in Wales and England.

Mine water heat is geothermal energy which could help the UK decarbonise its heat supply and meet net-zero emissions targets.

Dr Alison Monaghan, the science lead at the Glasgow Observatory, says its boreholes "are giving us an unprecedented look into the subsurface".

"Data from underneath Glasgow can now be used by scientists around the world to close the knowledge gaps we have on mine water heat energy and heat storage," she says.

The new information includes drilling logs, hydrogeological test data and images taken underground.

The images show fractures in the rock core from underneath Glasgow

The data is open for scientists to use, and the observatory team hope that researchers from around the world will get in touch to use the boreholes and better understand the subsurface.

The boreholes beneath Glasgow Observatory are expected to produce data for the next 15 years.

Upcoming data releases will include details of groundwater chemistry and pump test results, all in the cause of harvesting cheap and carbon-free energy.

But why stop at 199 metres rather than a nice round 200?

Going to 200 might be neater but it would involve more regulation and paperwork - and there is nothing that extra metre could tell them that the researchers will not have gleaned from the first 199.

This is one boring story that's actually quite interesting.