Covid: Arran pubs forced to close despite four months with no cases

- Published

The Pier Head Tavern in Lamlash will be closing for 16 days from Friday evening

Pubs and restaurants across much of Scotland's central belt will have to close for 16 days from Friday. The measure is being enforced to slow the surge in Covid-19 cases there, which the Scottish government says is being driven by hospitality. But not all areas inside the new restricted zone have high levels of cases - and some have none at all.

Jane Howe arrived at her Isle of Arran pub early on Thursday morning to work out how much beer she will have to pour down the drain.

"I've got five casks of real ale that cost £100 to £170 each. That's 52 pints a cask. We're not going to sell out of that before tomorrow but it won't keep," she says.

"I don't want to look, it's so tragic."

Like all other pubs and restaurants across five health board areas in the central belt, the Pier Head Tavern in Lamlash will have to close its doors at 18:00 on Friday and keep them closed for more than two weeks.

For Jane and her husband Alastair Howe, who have owned the pub for about five years, the enforced shutdown will be "devastating".

Jane Howe says she will need to throw away hundreds of pounds worth of beer

"We have to make enough money in the summer to keep us ticking over through the winter. We need to be open these next four weeks, but now we haven't got that," she says.

"The October break would have been an opportune time to make a bit of money and now it's gone."

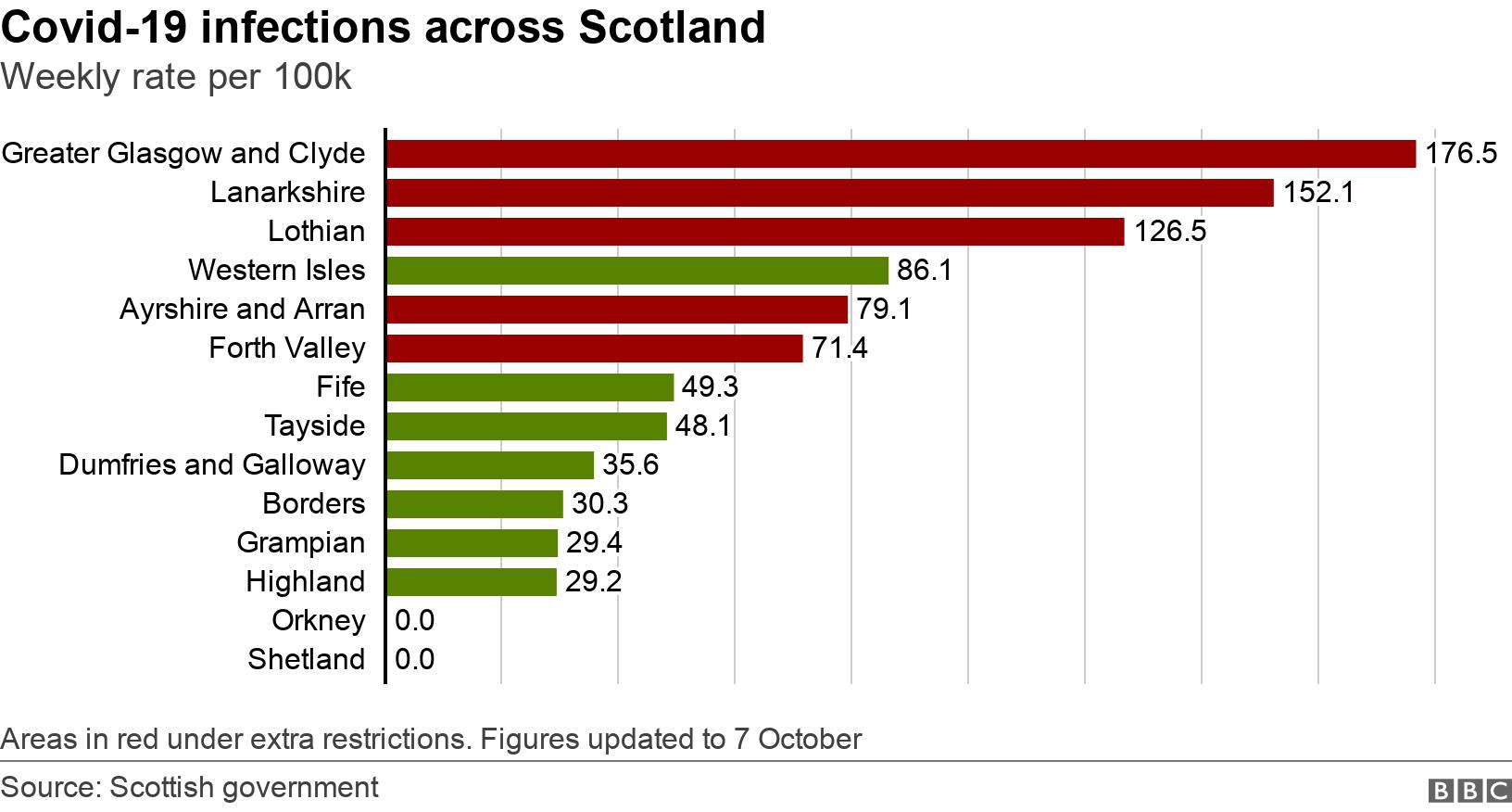

The Scottish government has picked out five central belt health boards for extra restrictions because they have a much higher rate of Covid-19 infections.

In the seven days up to 7 October, there were almost 180 cases per 100,00 people in NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Rates in NHS Lothian and Lanarkshire were also well over 100.

The rates are lower in NHS Ayrshire and Arran and NHS Forth Valley, but the Scottish government has suggested, external there may be a "ripple effect" of infections arriving from more badly affected areas.

So far, there is no evidence of the ripples reaching the Isle of Arran, where there have been no positive tests for Covid-19 since May - but businesses there still have to abide by the rules in force on the mainland.

Ms Howe says the restrictions are "grossly unfair" on an island which, according to an update from Arran Medical Group on 27 September, external, has only recorded five positive tests since the outbreak began in March.

"We're being tarred with the same brush as the rest of North Ayrshire. But it's a very different prospect out here. We don't have people drinking pint after pint. That doesn't happen," she says.

Ms Howe contrasts the infection risk inside her pub with a supermarket, where she says more people are gathering with less respect for social distancing.

The Howes have owned the Arran pub for about five years

The focus on hospitality also marks a distinct change in direction from the Scottish government in its attempts to slow down the rate of new coronavirus cases.

In early September, when a visiting ban was introduced in Glasgow city, West Dunbartonshire and East Renfrewshire, pubs were allowed to remain open.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney said then there was no evidence the growth in cases in those local authorities was being driven by hospitality - unlike the situation in Aberdeen a few weeks earlier, when pubs were forced to close.

"The problem in Aberdeen stemmed from the hospitality sector, so we had to focus on the hospitality sector," he told BBC Scotland on 2 September.

"Here in Glasgow, we don't have evidence of that taking its course, so it would be inappropriate and disproportionate to take that action."

Now, the Scottish government's evidence paper talks of the reopening of pubs and restaurants playing a "significant role" in moving the R number above one in early August, and of alcohol having a "disinhibiting impact" on behaviour and social distancing.

But it's not a situation that Jane recognises in her own pub, which she says is a "very calm, socially distanced environment".

"We're not even a pub any more. The bar is closed. Everyone is sat at a table and we operate as a restaurant. Now we can't even do that."

The Douglas Hotel has furloughed its staff for two weeks

A few miles north in Brodick, the general manager of the Douglas Hotel agrees that bars and restaurants are now highly regulated places.

Kate Russell says all her staff use PPE, there are "constant" checks, no music and generally there's a pretty strict regime in place to minimise the risk of infection.

Although exemptions do apply to hotels, Ms Russell says the Douglas Hotel will close for the full two weeks as it would not be financially viable to stay open for very few guests.

"As soon as the announcement was made yesterday our phone started ringing with cancellations," she says.

"At this time of year, lots of our guests come from all over Scotland and many can't travel here now. Others were saying they want to wait for when they can stay up a bit later and have a drink."

All the hotel staff will be furloughed for the 16 days.

Ms Russell says the hotel will now miss out on "three huge weekends" of business before the winter.

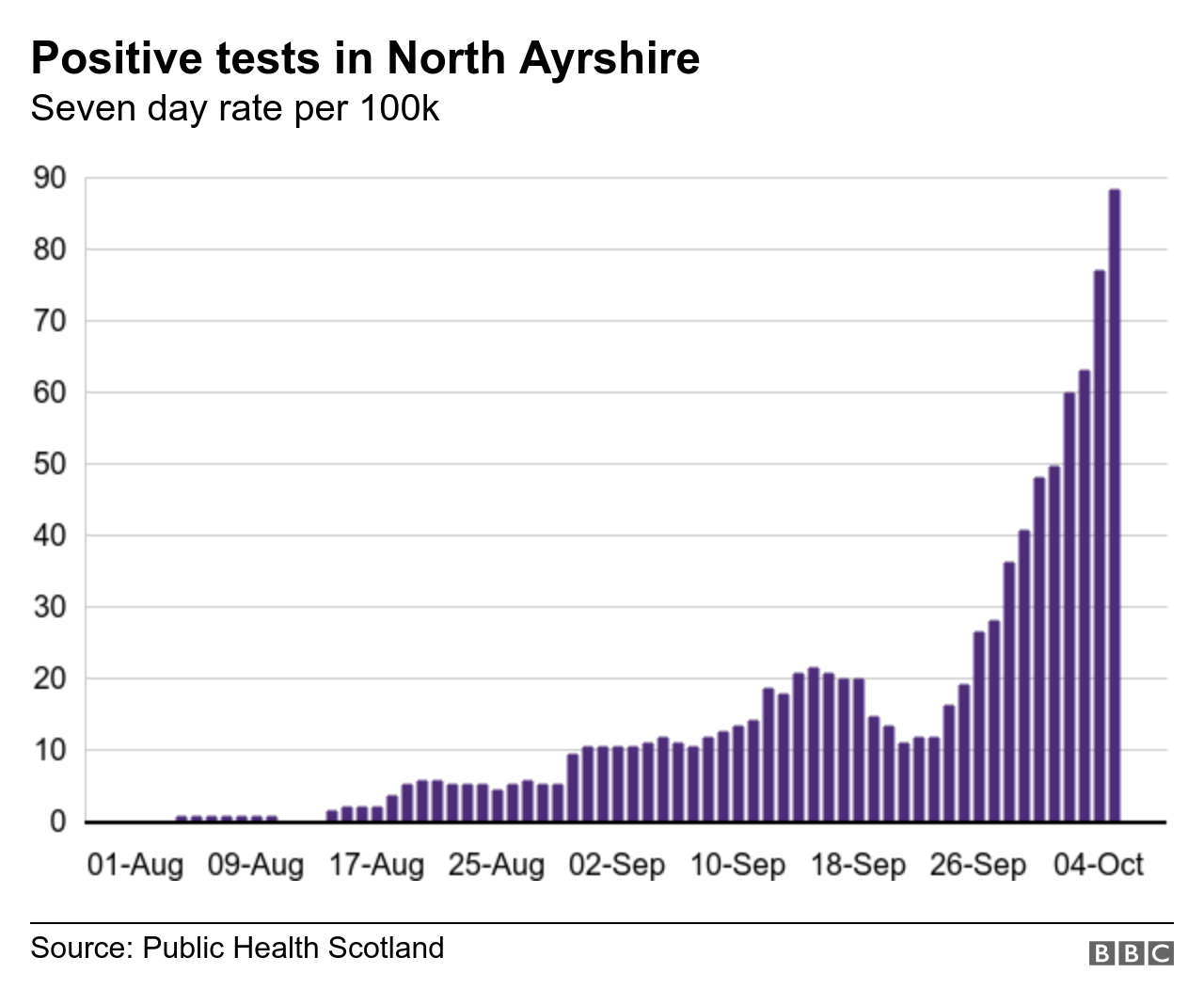

Positive tests in North Ayrshire have risen steeply in recent weeks - but none of them have been in Arran

"There are no cases on the island, haven't been for months, but we're part of NHS Ayrshire and Arran" she adds.

"We have to keep the staff safe and the island safe - but hospitality has been hit so bad."

In Lamlash, Ms Howe says she can't put her staff on furlough and doesn't yet know how much support they will get from the £40m set aside by the Scottish government to support the sector.

Ms Howe says she and her husband have spent years investing in what was a "derelict building", as well as building the pub's reputation as a live music venue, and were just beginning to see the benefits of that work.

"This is the first year we've started to make money. But now we're in an absolute mess," the former deputy head teacher says.

"How are we going to cope? I don't know."

- Published8 October 2020

- Published1 July 2022