'Rare condition gives me TV static in my vision'

- Published

The dots do not stop Paris from appreciating nature and she hopes to find work in wildlife conservation

For as long as Paris Haigh can remember she's seen tiny flickering dots in her vision.

The dots look like TV static, and they're a constant presence in her life.

The 19-year-old can see them when she goes shopping. They're with her when she studies at college. She can even see the dots when she closes her eyes.

Paris, from East Kilbride in South Lanarkshire, assumed for many years that everyone else could see them too.

When she discovered this wasn't the case, she put it down to her autism and sensory processing disorder - a condition which causes her senses to be especially sensitive.

She then went from thinking that everyone could see the dots to wondering if she was the only one in the world who could.

But then Paris heard about "visual snow" - a little-known neurological condition which causes visual and non-visual symptoms.

'Big layer' of static

One study has estimated, external the condition could affect up to 3% of the UK population, but it's not clear exactly how many people have it.

The main symptom of visual snow is continuous tiny dots in the patient's vision, which differ in colour and severity from person to person.

"It's like a big layer of TV static which covers my whole entire vision, 24/7 non-stop," Paris said.

"I can even see it when I close my eyes."

Other people have described it as having a sort of pixelated vision.

Paris says she is able to filter out the dots for much of the time, but some days are harder than others.

"There are some days where it's in my face all the time. It can be quite distracting," she said.

What does visual snow look like?

This photograph of Glasgow has been altered to demonstrate how Paris's vision is affected by the visual snow condition

Digital artist Zytomania created this image to show what his own visual snow is like

Certain things can cause the flashing dots to become more noticeable.

For Paris, it is tiredness, anxiety, headaches or whenever she is in very bright or dark settings.

Using cosmetic products can also cause problems.

"I don't really wear make-up, but when I wear eye shadow it stings my eyes and for days afterwards my visual snow is so bad that I can hardly see," she said.

Paris wears special orange-tinted glasses when reading to help with her sensory processing disorder.

She said the glasses also helped with her visual snow, but they don't eliminate it.

"Sometimes the words kind of have an aura around them, or else I'll see a double of the word in purple above it. Mostly it's just kind of flashing or the space between the words will appear as a river down the page and make the words ripple," she said.

Paris also suffers from mild tinnitus - a condition which is strongly linked to visual snow

As well as the visual snow itself, Paris also experiences "after images", which cause her to see images even after looking away.

She also describes seeing random colour flashes, pulsating vision and night-blindness.

"I need a night light every night because I'll start to get darkness that creeps in from the edges of my eyes and it will start covering my whole vision until it goes completely black, except for the dots," she said.

Before Paris knew what visual snow was, it caused her quite a bit of stress and anxiety.

"I remember one time, sitting in school, my eyesight just kept deteriorating for like an hour or two. People's faces were going fuzzy and I was just convinced I was going to go blind," she said.

'Visual tinnitus'

Despite living with the condition her whole life, Paris only learned what visual snow was when she was about to turn 18.

"One day it looked like it was pouring down [with rain] but there was nothing there in reality. So I thought, 'right I'm just going to Google this'."

When she typed her symptoms into the search engine, visual snow came up right away. Learning about what caused the static dots in her vision was a relief for Paris.

"Because I know what it is now and that it's not dangerous, that's already made me feel a lot better. I can function better," she said.

Prof Jon Stone, a neurology consultant and honorary professor of neurology at the University of Edinburgh, has seen patients with visual snow.

He told BBC Scotland the condition was caused by a problem in the way the brain handled visual information.

"Normally our brains are good at filtering out visual experiences we don't want," he said.

"This filtering system doesn't work as well in people with visual snow, probably because parts of the visual system in their brain are overactive in an unhelpful way.

"It's a bit like having tinnitus, but of your vision."

Formal diagnosis

Prof Stone said that while more opticians and ophthalmologists were becoming aware of the condition, sometimes it could take a while for a patient to meet one who does recognise it.

According to the Visual Snow Initiative - a US charity dedicated to visual snow research - about 56% of people with the condition are misdiagnosed.

Paris is hoping to get a formal diagnosis for her visual snow, but she said it had been a frustrating experience.

She has talked to an ophthalmologist and neurologist about the condition, but felt that they didn't know what it was.

"It can feel like a made-up condition when experts have no clue what it is," she said.

Paris has an upcoming appointment with a neurologist for a separate issue and hopes that she will be able to raise the issue then.

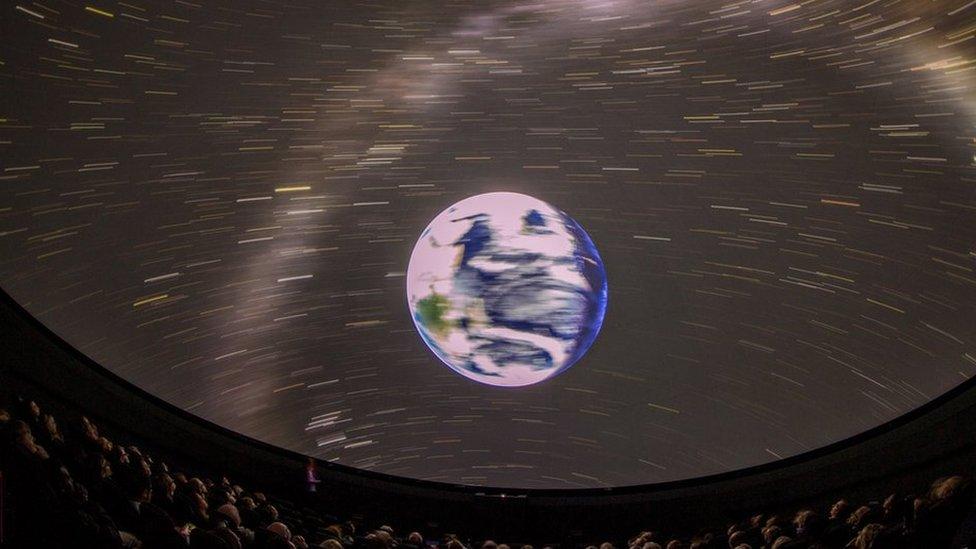

When Paris was younger her parents took her to a planetarium but her visual snow made the experience frightening

Despite the worries she once had about it, Paris now believes it would be strange if she stopped seeing the static.

When she was a child she visited the planetarium in the Glasgow Science Centre but was too afraid to go in.

"Because I was too scared to go I would sit in my room and pretend I was in my own planetarium," she said.

"I could see all these stars around me in my vision and I would be my own kind of planetarium commentator."

Her visual snow has become more noticeable recently and she thinks that is a result of her awareness of it, rather than the condition becoming more severe.

"It's relieving to know that it is nothing to do with my eyesight and it's not dangerous. It's just a weird brain processing thing," she said.

"A lot of people want a cure for it but I wouldn't take it if there was one. It can be quite pretty."