Are 20-minute communities the future of cities?

- Published

More than 3,500 homes that are being built in the north of Glasgow will become Scotland's first completed 20 minute community

With climate change and the cost of living on many people's minds at the moment, governments across the world are scrambling to find solutions to these ongoing crises.

One idea gaining traction around the globe is 20-minute communities, where people can meet their daily needs within a 20-minute walk or cycle from home.

They have already been introduced in cities such as Paris and Melbourne, and the thinking behind them is that they're good for the environment, people's physical and mental health, and affordable living.

The Scottish government says it will deliver on its own vision for 20-minute communities during this parliament, with a new emphasis on local living.

Meanwhile, 16 of Scotland's 32 local authorities told BBC Scotland they had similar plans.

"Scotland is the first country to put this in national planning policy as far as I'm aware," said Stefanie O'Gorman, director of sustainable economics at Ramboll.

"The opportunity here now is to do something different and put Scotland on the map in this context, because in other countries it is being applied very specifically in a city".

Previously disused pathways have been reopened around the new development, which is close to the city's smart canal

She said there was potential to deliver on 20-minute communities in both rural and urban areas, with changes made, for instance, through repurposing existing spaces to provide improved or new pathways.

But the purpose of living locally isn't just beneficial to fighting climate change.

Ms O'Gorman said: "If you look at the statistics for transport poverty, it's a real and growing issue across the country. This has the opportunity to reduce that by providing people with alternatives to do what they need to do.

"While getting out of your car is good from a climate change perspective, it's also good from a cost of living perspective.

"People don't have choices in many cases, and this is about giving people a choice."

Construction work currently under way in the North of Glasgow will transform some of the city's most deprived areas into Scotland's first completed 20-minute community.

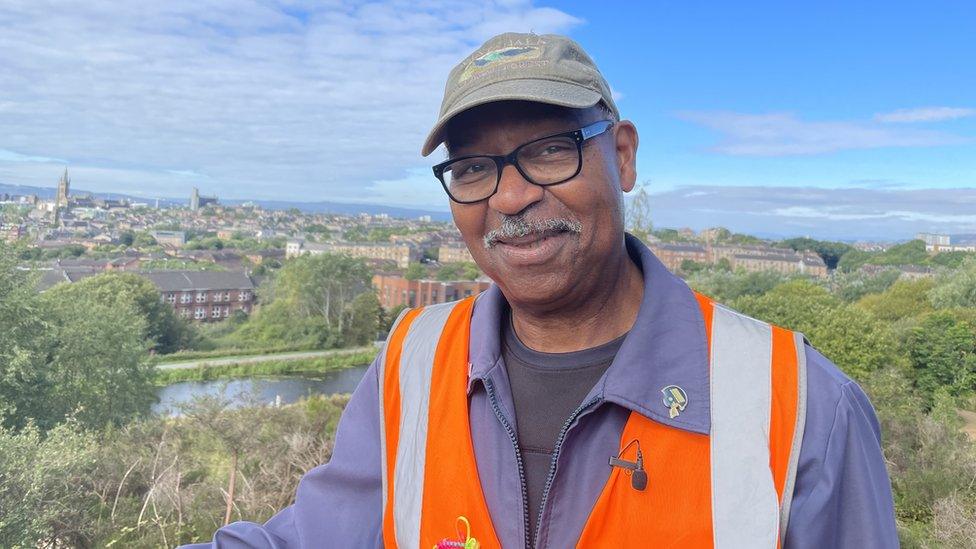

Bob Alston said the development work had totally transformed the local community

There are 3,500 new homes being built in Sighthill and Dundashill, which will be a mixture of private and social housing. The development is currently one of the largest construction sites outside of London.

This is due to extensive flood prevention work on Glasgow's smart canal, which was switched on last year during Cop26 and has won international engineering awards, and has also allowed an inner city nature reserve called the Claypits to open.

Previously disused pathways are now reopened, and a small bridge has reconnected different communities.

"We've got two health centres in the area, Possil health centre and a Woodside health centre, and these paths connect the two, which was impossible before," said Bob Alston, one of the local volunteers that helps maintain the reserve.

"It's brilliant. We're only a 20-minute walk from Sauchiehall Street here, and we have a 17 hectare mature reserve in land that was literally forgotten about."

He said the space had opened up activities along the canal once more, and that it had "totally transformed" the community.

"It encourages people to come out and walk, and to talk to other people," he added.

"So it is a help physically, but also a help mentally."

Nicol Wheatley said the project was allowing different communities to connect with each other

Beyond the nature reserve, extensive work is under way to link communities further.

The Stockingfield Bridge, currently under construction and set to open in September, has been built to reconnect the three districts of Gilshochill, Maryhill and Ruchill.

"These communities had been separated since the canal was built about 150 years ago," said Nicol Wheatley, who is artist curator of the project.

"It's a great thing for North West Glasgow, as it gets these districts back in touch with each other, and it vastly increases active travel."

The bridge is being decorated by local artists and residents, including thousands of handmade mosaic tiles made by people who live in the area.

"It's become really important to the community because they've all got a piece they know they can walk up to the bridge and see, and potentially come and find their own tile and tell that story through their families," Ruth Imphie, one of the artists involved, said.

And while there are concerns that the work under way could eventually price locals out of living in the area, Louise Nolan believes that's a risk whenever money is spent in an area.

"There's a very high proportion of people that live in this community, you know, we're working class, a housing association tenant, or council tenant, but we're proud of the area and part of the solution to the changes happening here as well, and we want to be part of that process," she said.