Grieving father's anger at care of son assessed as 'low risk'

- Published

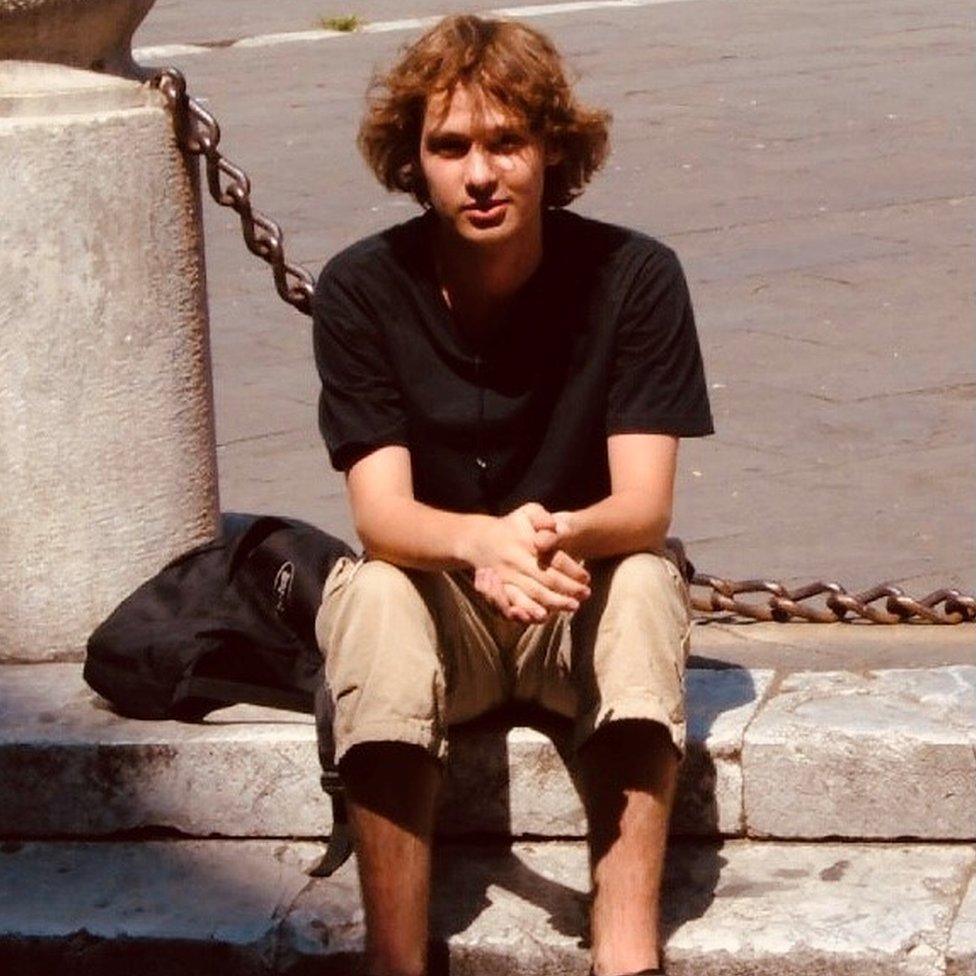

Adam Parry died age 32 after multiple alcohol withdrawal seizures

A grieving father has voiced his anger that a health board failed to flag his son as being vulnerable one month before he died from alcoholism.

Adam Parry died at the age of 32 after having multiple seizures due to withdrawal.

A review of his care, which is in draft form, found that Adam should have been a priority case - but was marked as "low risk".

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde apologised to the family.

It also said addiction services had remained open through the pandemic despite being impacted by Covid.

However, Adam's father Fred Parry told the BBC he believed addiction services were not working.

"It's not good enough to keep blaming staffing and Covid, my son had this for 12 years," he said.

Mr Parry, from Glasgow, described Adam as a well-spoken, highly intelligent young man who was always reading two or three books at a time.

His addiction became prominent when he started studying chemistry at the University of St Andrews. He had failed exams, which led to him dropping out altogether.

Adam dropped out of the University of St Andrews after his addiction worsened

He attended rehab at Castle Craig, a private hospital in the Borders, and stayed sober for three years, but began struggling again in 2017.

While unemployed and living with his parents, Adam's drinking became more erratic and he began having alcohol-related seizures.

On 6 May 2021 he died in his room, his body blocking the doorway.

"There's not a day goes by when I don't hear Adam hitting the floor," Mr Parry said.

'Not seen as vulnerable'

Originally reported in The Ferret, external news service, a Serious Adverse Event Review (SAER) noted Adam had five seizures in five months. A sixth seizure contributed to his death.

In those months, the review found he should have been highlighted as a priority due to the number of hospital admissions "but was not seen as vulnerable".

The review also found problems which included communication issues, poor record-keeping and staff shortages.

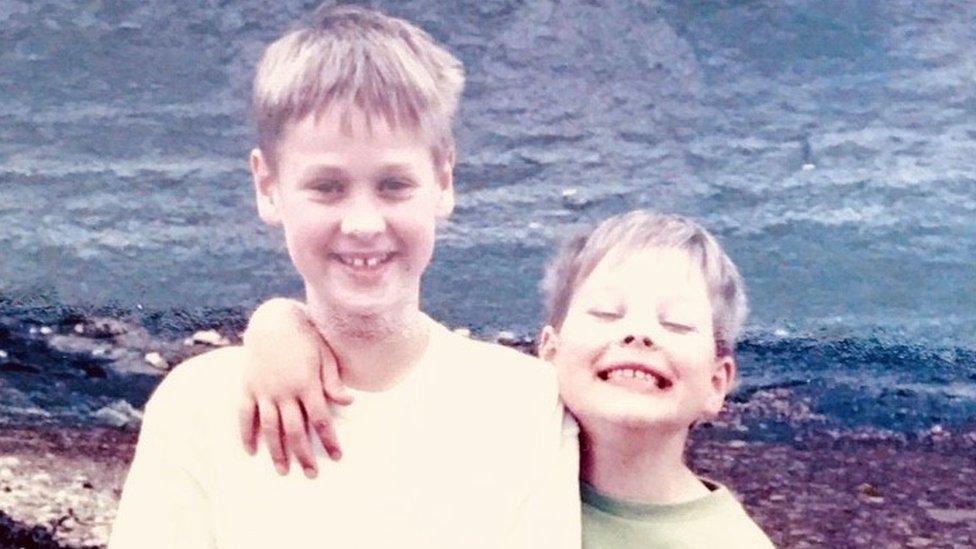

Adam, left, and his younger brother Fraser

Despite the assessment that Adam had a supportive family, there was nothing in his case notes about family involvement or next of kin details, the review said.

His GP had no contact with the family, but noted that he was "non-compliant" on medication.

The review states: "The care and treatment provided to this patient was satisfactory with perhaps, an overly optimistic assessment of risk and reliance on protective factors."

However, it concludes that the issues identified "may have caused or contributed to the event [his death]".

'The system doesn't work'

The review notes that Adam's family received an apology, but his father said he was disappointed with how it had been worded.

"No parent should have to do this," Mr Parry said.

"I shouldn't have to go through all this to find out about my son's care or lack of care - because there is no doubt in the report there are obvious failings they've admitted to. But they always stop short.

"There's no word of how they would implement any of the things they're going to rectify. A lot of it is just words, I don't see action.

"I've never said it's an easy job and I don't want to blame individuals - I blame a system that doesn't work."

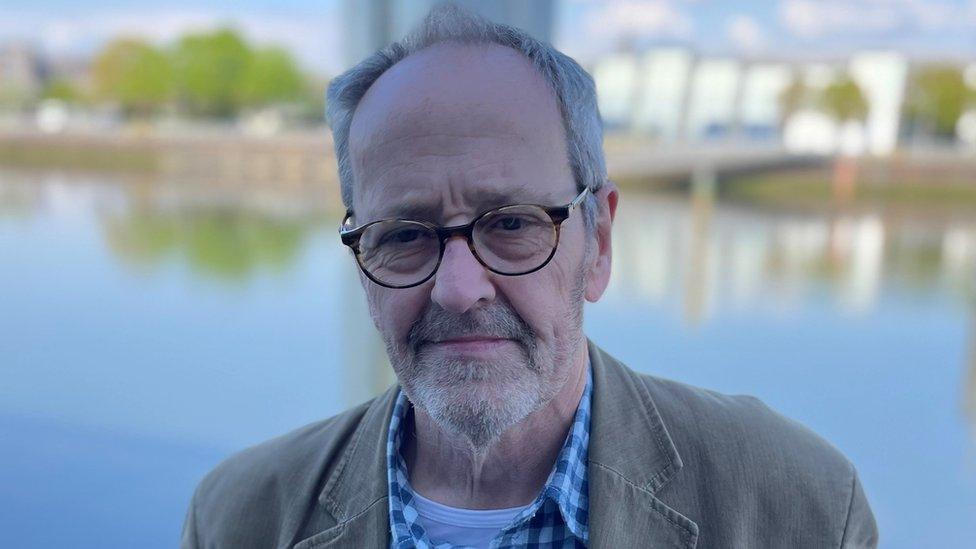

Music teacher and cellist Fred Parry spoke to the BBC about his son's battle with alcohol addiction

Mr Parry, who also struggled with alcoholism, credits his 20-year sobriety to the time he spent in the Castle Craig clinic.

The 66-year-old is now a cellist and a music teacher, and describes himself as "living proof" that rehab can be effective.

The SAER report said Adam did not ask for this service through the NHS. However, Mr Parry said this was something he had asked for, and that he had considered paying for his son to undergo treatment a second time.

The Scottish Conservatives lodged a draft Right to Recovery Bill at Holyrood in May. If passed it would enshrine the right to receive "potentially life-saving" treatment in law, including residential rehabilitation.

The party hopes the legislation will help tackle Scotland's drug deaths, which are still the highest in Europe.

Mr Parry believes there is also a lack of understanding about addiction within the health service, and that families are expected to deliver more support than is possible.

Adam repeatedly told addiction staff he was stable and was deemed capable of making decisions about his own care.

As a result, his parents were not told about his prescriptions, and he often missed appointments and stopped taking medication.

"You are assumed as being a carer with one or both hands tied behind your back," Mr Parry said.

"If someone is an addict, whether drug or alcohol users, then they're not functioning properly. So they won't keep appointments.

"He was a well-spoken, educated young man who didn't present the way people perceive alcoholics to be."

Mr Parry said the family had been taken for granted.

'Impacted by Covid'

"They assumed because we live in a nice, middle-class area we were going to be supportive," he said.

"We were his family, his sister, his brother, his mother, his father - we weren't his addiction counsellors."

A spokesperson for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde said it could not speak about the circumstances of any case.

They said: "We apologise to Mr Parry and we're sorry the care his son received was not up to the standards he would have expected

"We would once again encourage Mr Parry to contact us so that we can continue to support him through this difficult time.

"Significant progress has already been made on actions and learning, and wider service remobilisation is increasing face to face contact with our patients. We will of course further implement any final lessons when the SAER is finalised."

- Published1 May 2022

- Published28 July 2022

- Published28 July 2022