Ten things we learned about Scotland's ferry fiasco

- Published

The "Shipbuilders of Port Glasgow" sculpture with Glen Sannox in the background

The decision to build two CalMac ferries at the Ferguson shipyard in Port Glasgow has led to years of controversy.

A BBC Disclosure documentary has shed new light on the saga. Here are 10 key things that we learned during the investigation.

1: Jim McColl was already looking at buying the yard before it went into administration

The Ferguson shipyard had been struggling for a decade as it was undercut by overseas shipbuilders, particularly in Eastern Europe.

Since 2012 it had been kept going with orders for two small diesel/electric hybrid ferries for CalMac, but the yard had lost so many key staff it felt unable to take on a third order. Scottish Enterprise was aware of its financial problems.

Businessman Jim McColl confirmed to BBC Disclosure that he looked at the business at least two months before it went bust. Senior people from his Clyde Blowers Capital investment company visited the yard to look at the business potential.

Jim McColl confirmed that he looked into buying Ferguson before it went bust

He said this "whetted our appetite" but it was too "messy" to buy the yard at this stage as there were problems, such as debts, which administrators would need to clear up.

The BBC understands that one issue deterring potential buyers was an underfunded final salary pension scheme.

The former owners hoped workers would be kept on during the change of ownership, but within hours of administration most were made redundant.

2: CalMac's specification was based on a ship designed for a Swedish route

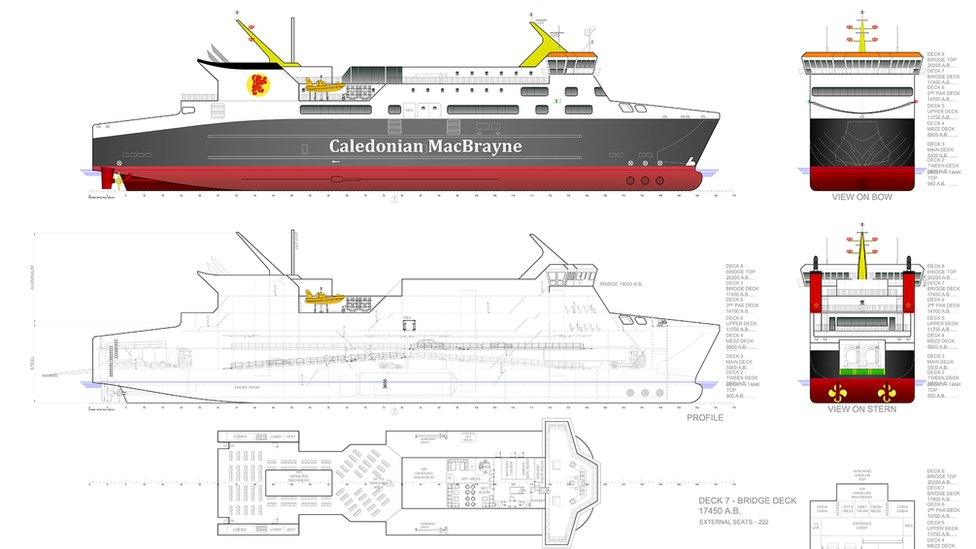

The Scottish government gave the go-ahead for the procurement of two new large CalMac ferries in the summer of 2014, with the original plan to name the preferred bidder by end of March 2015.

A leaked email from early July reveals that the head of vessels at its procurement agency CMAL believed such a timetable would be "hugely challenging".

Despite this warning, this timetable was adopted, giving ferry operator CalMac just three weeks to draw up its Specification of Technical and Operational Requirements.

CalMac produced an unusually detailed 424-page document, much of it adapted from a ship design it had worked on during an unsuccessful bid to run a Swedish ferry route to Gotland.

In the rush, some errors slipped though, such as references to "passenger cabins" which were not relevant to CalMac ships.

The procurement timetable was later extended, with preferred bidder not announced publicly until 31 August 2015 and contract signing in October.

3: Ferguson was allowed onto the shortlist despite not meeting a mandatory requirement

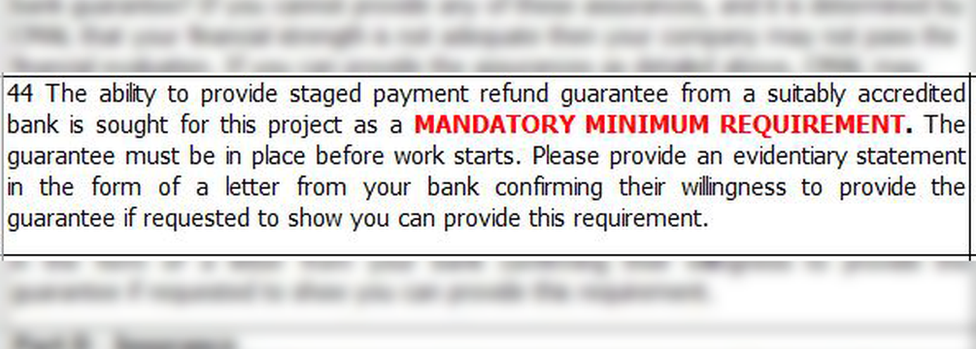

Evidence that a builders refund guarantee could be provided was a mandatory requirement before being allowed to bid

The ferry procurement was run under something called a restricted procedure that meant interested shipyards had to fill out a "pre-qualification questionnaire" or PQQ - in effect a screening process to select who would be invited to tender.

As well as assessing shipyards' capabilities, it set out the requirement - written in red capital letters - for evidence confirming the yard could provide a Builder's Refund Guarantee, which protects any advance payments issued by the buyer. This was to be provided in the form of a banker's letter.

CMAL has previously said that during the tender process Ferguson made "no comment" on a section of the draft contract relating to guarantees - and it took this as "tacit acceptance" of the condition.

The BBC Disclosure investigation, however, uncovered emails from December 2014 which show Ferguson had already made it clear to CMAL that as a newly-formed company it was struggling to obtain a bank guarantee.

It initially filled in the PQQ questionnaire saying only that it would "endeavour to comply with your request".

When this was queried, it said it was having discussions with the Scottish government regarding "bonding for ship contracts in general" and that the issue will "hopefully be sorted". It also stated that it did not believe a parent company guarantee was appropriate.

On this basis CMAL's finance director approved Fergusons' progression to the shortlist.

Ferguson had been given a £12m order from CMAL a few weeks earlier for a small ferry, MV Catriona, without a requirement for such bank guarantees.

4: Assessors knew whose bids they were scoring

In the scoresheets the seven competing designs were labelled A-F, giving the appearance of an anonymous process.

In fact the bids were only anonymised for a small section of the evaluation involving an independent technical expert and a review by CalMac.

Emails seen by the BBC show that CMAL's assessors clearly knew the identity of the shipyards they were scoring.

At the start of June the assessors invited Ferguson's managing director and chief naval architect to a "strictly confidential" face-to-face meeting at the shipyard to discuss "clarifications and perceived inconsistencies" in their submission. No other shipyard was offered a similar in-person meeting.

While clarification questions are a normal part of tender evaluation, for other yards they consisted of a simple list of numbered questions. Four days after the face-to-face meeting, Ferguson's architect was sent a full copy of its technical document with issues highlighted in yellow marker pen.

5: A key document gave Ferguson an advantage

The procurement process began in July 2014 with ferry operator CalMac drawing up its Specification of Operational and Technical Requirements (SOTR).

This 424-page document was then distilled down to a much shorter 125-page technical specification that was issued by CMAL to shortlisted bidders.

Ferguson copied a large section of its bid from a CalMac document

Ferguson had a big advantage because it had access to the original SOTR. The majority of its 351-page technical submission was cut and pasted from the CalMac document - including the font, numbering and minor errors or typos.

As part of the evaluation, CalMac was invited to comment on how well the three shortlisted designs met its requirements, before CMAL scored them.

When the second-placed shipyard later queried its low score, it was told by CMAL that Ferguson's technical document was longer and more detailed.

CMAL has said that, to the best of its knowledge, it did not supply the SOTR to Ferguson.

The BBC understands Ferguson obtained it from design consultants who had also worked on preparing the original tender documents for CMAL.

During a Holyrood inquiry two years ago, CMAL officials said they saw nothing problematic about the same company being used for both roles.

6: CalMac's experts thought a rival bid was better

Despite the advantage of having access to CalMac's own specification document, a report by a CalMac naval architect still found the design by Remontowa best matched its requirements, with Ferguson ranked second.

CMAL's assessors later gave the Polish yard a "poor" score, while Ferguson was ranked as "good" in this section of their evaluation.

CalMac's review warned that all the shortlisted ship designs were underdeveloped, and that major issues would need to be resolved to "avoid costly variations and delays during design and build of the new ships".

7: Ferguson's design changed significantly after the submission deadline

Ferguson was allowed to resubmit drawings for a much lighter ship

The deadline for bids was 31 March 2015, and they were to be assessed 50% on cost and 50% on quality.

The "quality" assessment began with a consultant naval architect being asked to compare and comment on the competing designs.

Ferguson's design was the heaviest ship, requiring the largest engines. This could have led to it being discounted - a rival design with a smaller power requirement was eliminated for this very reason.

CMAL's assessors, however, focused on a small section of the Ferguson bid that referenced early computer modelling on a lighter ship known as Model 10.

The simulations had prompted concerns this design would struggle to meet the demanding deadweight - or cargo carrying - requirements, so instead a bigger ship known as Model 20 was developed.

Ferguson's initial design submission was based on Model 20 but on 17 May, CMAL's assessors asked Ferguson to give it more details of Model 10 - then scored it on this revised design.

8: Ferguson's initial price was £37m higher than the cheapest bid

When the bids were opened, Ferguson's price came in at £109.8m - while the cheapest was £72.8m,

The scoring formula allocated points based on the difference between a shipyard's price and that of the cheapest, so Ferguson would have scored very poorly.

However, when it was asked to submit a lighter Model 10-based design, it also dropped its price to about £101m, giving it crucial extra points. It later fell to £97m.

The gap was narrowed further by adding in estimates of extra costs such as site supervision. While £1.3m was added to the Ferguson bid, a shipyard in Turkey had £4.5m added to its price.

Ferguson emerged with 36.5 points out of 50 in the cost assessment - in last place but with a deficit sufficiently small to be overturned by an exceptional score for quality.

CMAL gave Ferguson 38 points in the quality assessment, nearly 10 points more than its nearest rival, making it the winner overall.

9: CMAL and CalMac were often at loggerheads over the design

CalMac was unhappy with CMAL's initial draft of the specification to be sent to shortlisted bidders.

Just a day before Transport Minister Keith Brown publicly announced the start of the procurement in October 2014, CalMac complained that CMAL's document only met 20% of its requirements.

The tender documents ended up being a compromise, specifying a wider ship than CalMac believed compatible with many existing port structures.

CalMac later complained that the wider ship designs required bigger engines, potentially adding £1m to its annual fuel costs.

After the contract was awarded, Ferguson's design team carried out model testing with CalMac's preferred smaller engine size, but found it was unable to deliver on other key requirements.

CMAL and CalMac eventually agreed to relax some specifications in order to go with the smaller engines - but it led to delays in detailed design work.

Ferguson's new managers, meanwhile, were pressing ahead with the build to hit production milestones agreed with CMAL.

The final hull shape was not settled until the following February, by which time 60% of the steelwork had been completed on the first ship.

10: Workers had no confidence in 'turnaround director' Tim Hair

Tim Hair was paid nearly £1.3m during his time as turnaround director

After nationalisation, Tim Hair was appointed as "turnaround director" - with a daily pay rate of £2,850 initially - following a phone interview.

Union representatives praised Mr Hair for offering permanent contracts to temporary staff, but later became worried by slow progress despite high numbers of highly-paid managers and supervisors being taken on.

Concerns were also raised about the rationale of erecting the funnels and masts on the first ship when vital equipment for these structures was not yet fitted.

BBC Disclosure learned that matters came to head in November when the workforce representatives told the board of directors, external they had lost confidence in the senior management team.

The workforce also communicated this to Finance Secretary Kate Forbes, and the following month it was announced Mr Hair would be moving on.

He was replaced earlier this year, by which time he had been paid almost £1.3m for 454 days work.

The Great Ferries Scandal will be broadcast on BBC One Scotland at 20:00 on Tuesday 27 September.

Related topics

- Published27 September 2022

- Published27 September 2022