Pig vomit toxin key to Martian meteorite mystery

- Published

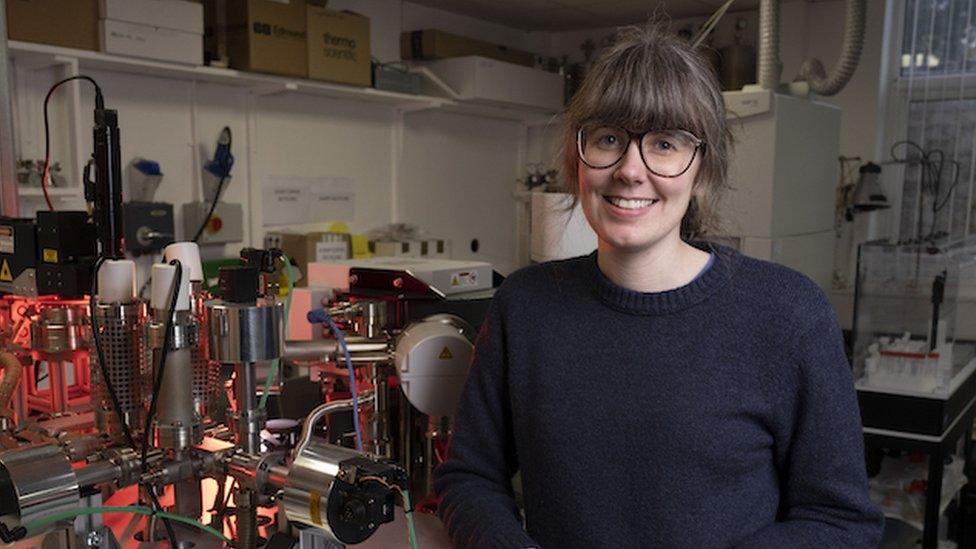

Dr Aine O'Brien was studying the organic content in Martian meteorites at the University of Glasgow

A science sleuth based in Glasgow may have helped solve a century-long mystery surrounding the discovery of a Martian meteorite thanks to a toxin which makes pigs vomit.

The Lafayette meteorite was found in the drawer of an American university's biology department in 1929 but nobody at the Purdue University in Indiana could remember where it came from.

One theory suggested that it was donated to them by a black student who witnessed it land in a pond while he was fishing.

Dr Aine O'Brien, an environmental and planetary organic geochemist at the University of Glasgow, began her detective work two years ago and it has now shed some light on who the black student might have been and when it was handed in.

Her work began when her team were given a small fraction of the meteorite by The Natural History Museum in London.

"It's a meteorite from Mars and these are really rare," Dr O'Brien said.

"That alone makes it really precious and not all of those meteorites from Mars are in as pristine condition as Lafayette.

"It must have been picked up pretty soon after it fell because otherwise the outer edge would have weathered away."

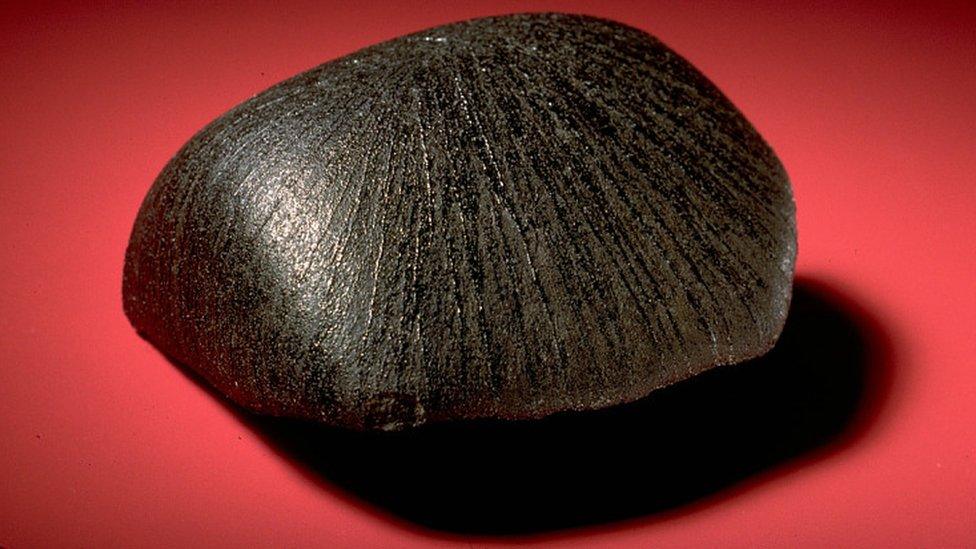

Most of the Lafayette meteorite is kept at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

Its pristine condition makes it perfect for researching.

Dr O'Brien crushed up the tiny piece of Mars and used sophisticated mass spectrometry to find out what it was made up of.

The point of the experiment was to look for preserved organic molecules- evidence which could help her learn more about the possibility of life on Mars.

"We ended up with a long list of hundreds of different chemical compounds," Dr O'Brien said.

"It was late March 2020, so I had nothing better to do other than just scroll through the list.

"Most of them had really long, boring chemistry data-type names but one was called a vomitoxin which I thought sounded cool so I started looking into it."

She discovered that the vomitoxin, deoxynivalenol (DON), was found in a fungus which contaminates grain crops like corn, wheat and oats.

It causes sickness in humans and animals when ingested, with pigs being particularly affected.

Dr O'Brien mentioned the vomitoxin to her supervisor, who told her that the origins of Lafayette's discovery were unknown and suggested that the fungus might affect crops in Indiana.

"That started this massive sort of rabbit hole, because it turned out it's a massive thing over there," she said.

"There was this assistant professor at Purdue University, Dr Marissa Tremblay who I knew because she used to be at Glasgow.

"I messaged her on Twitter and we, along with the university's librarian, started to do some detective work."

They turned to researchers at the university's agronomy and botany and plant pathology departments to learn more about the historic prevalence of the fungus in Tippecanoe County in Indiana, where Purdue is located.

Their records showed that it caused a marked drop in crop yield in 1919, and another less pronounced drop in 1927 - the highest prevalence of the fungus in the 20 years before 1931, when Lafayette was actually identified as a meteorite.

Her team suggested that dust from affected crops may have carried DON to surrounding waterways and Lafayette may have been contaminated with it, if like the story suggested, it fell in a pond.

Analysis of fireball sightings were also used to determine Lafayette's landing. Meteorites heat up as they descend through the Earth's atmosphere, causing a bright streak of fire across the sky.

There were reported fireball sightings across southern Michigan and northern Indiana in 1919, and one in 1927.

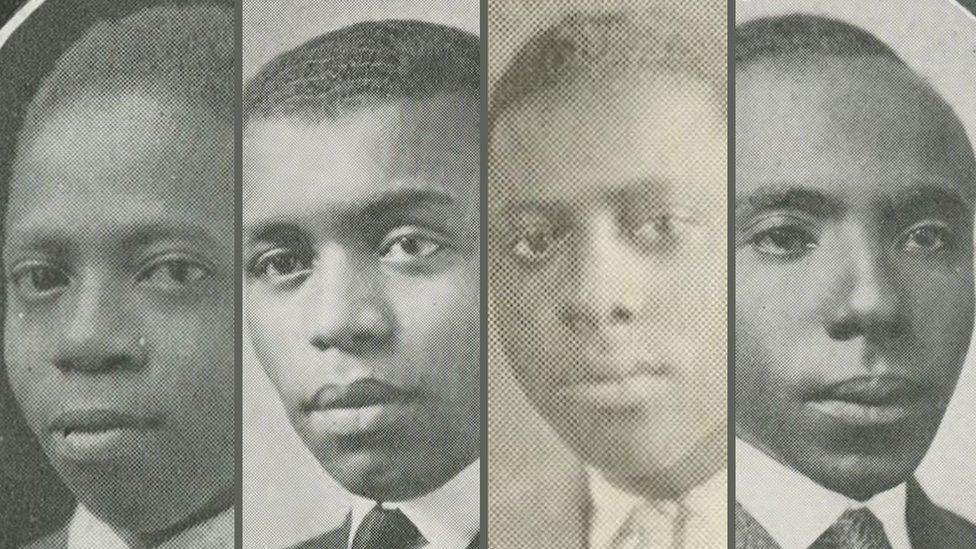

From left to right: Hermanze Edwin Fauntleroy, Clinton Edward Shaw, Julius Lee Morgan and Clyde Silance

Archivists at Purdue University then went through the yearbooks to find black students enrolled at the time.

Three students - Julius Lee Morgan, Clinton Edward Shaw and Hermanze Edwin Fauntleroy - were enrolled in Purdue during 1919. A fourth - Clyde Silance - was studying there in 1927.

The researchers believe one of these students may have found Lafayette as the previous origin story suggested.

"Lafayette is a truly beautiful meteorite sample which has taught us a lot about Mars through previous research," Dr O'Brien said.

"So for that alone, they deserve the credit right? You then add in the fact that they were an African-American student at a university that had so few. We all know the stories of racism in 1920s America."

Dr O'Brien admits that we may never know exactly which student discovered the meteorite but she is happy she was able to shed some light on the story.

"The only reason we were able to narrow it down was because the university had such few black students and this is Black History Month," she said.

"And this is a kind of Black history, I didn't want to shy away from the fact that this is a big part of the story."