Bible John: The forgotten women at the heart of a serial killer mystery

- Published

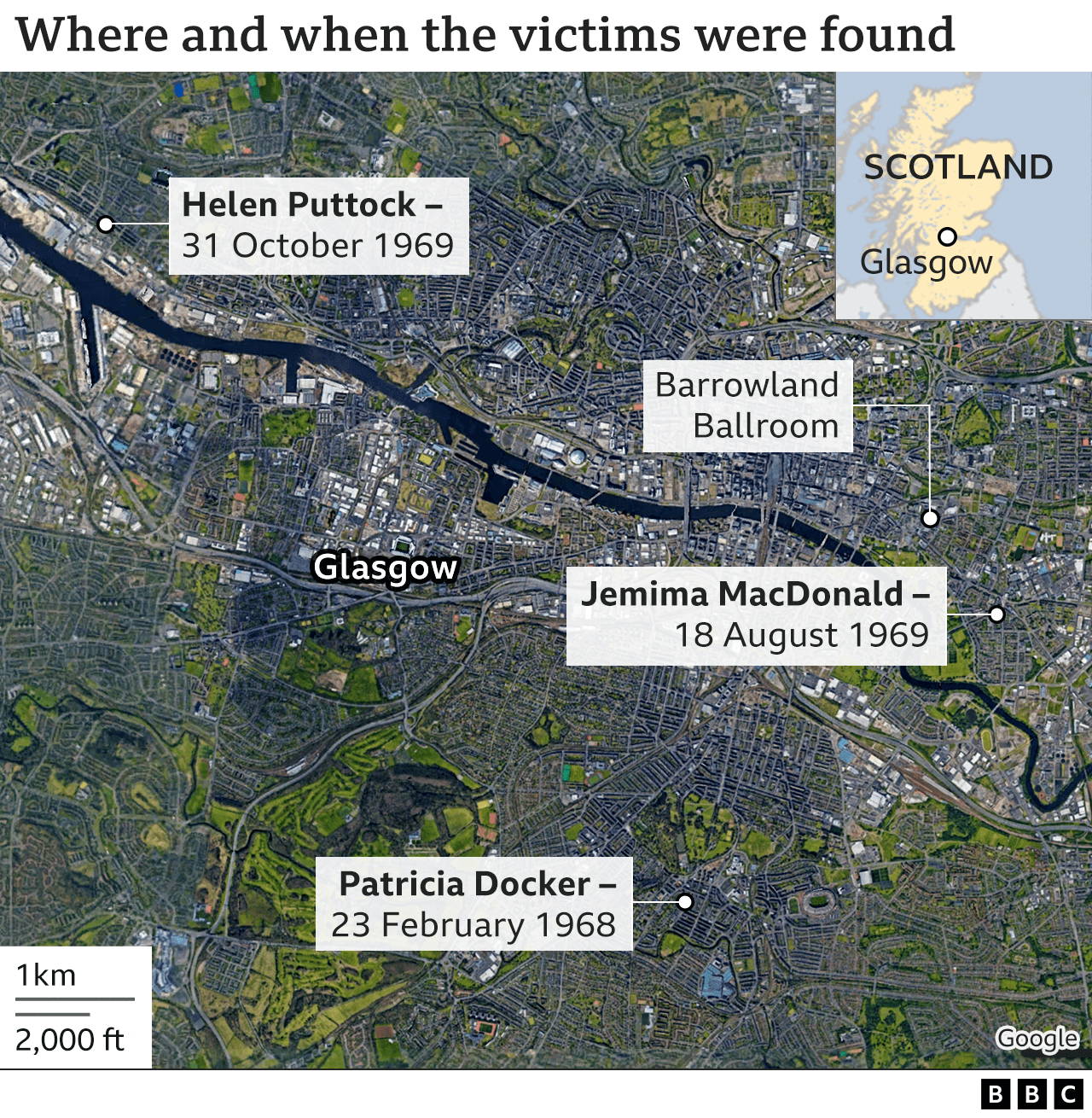

Patricia Docker, Helen Puttock and Jemima MacDonald were all murdered after nights out at the Barrowland Ballroom

Patricia Docker, Jemima MacDonald and Helen Puttock were murdered in Glasgow in the late 1960s. Their names became synonymous with Bible John - the man believed to have been responsible for all three killings. Journalist Audrey Gillan reassesses the case to find out who these women were and to tell their forgotten stories.

Each of the young women had gone for a night out at Glasgow's Barrowland Ballroom, leaving their children in the care of family at home.

They never returned to them.

They were all strangled and their bodies dumped just a short distance from where they lived.

Suddenly, there was a fear that a serial killer was on the loose, preying on women from the edge of the dance floor.

The search for the killer led to Scotland's biggest manhunt. He became known as Bible John, after one witness said he had quoted scripture.

As a young journalist in the 1990s, I was guilty of making Patricia, Jemima and Helen a footnote in a tale about this monster - Bible John. A monster who has never been caught, despite decades of speculation about his identity.

I reported the basic "facts" of this case. But I also repeated the mistakes. The major ones - that all three women were raped - and the smaller errors, like getting Jemima's age and the spelling of her surname wrong.

And I just assumed that they were "victims of a serial killer".

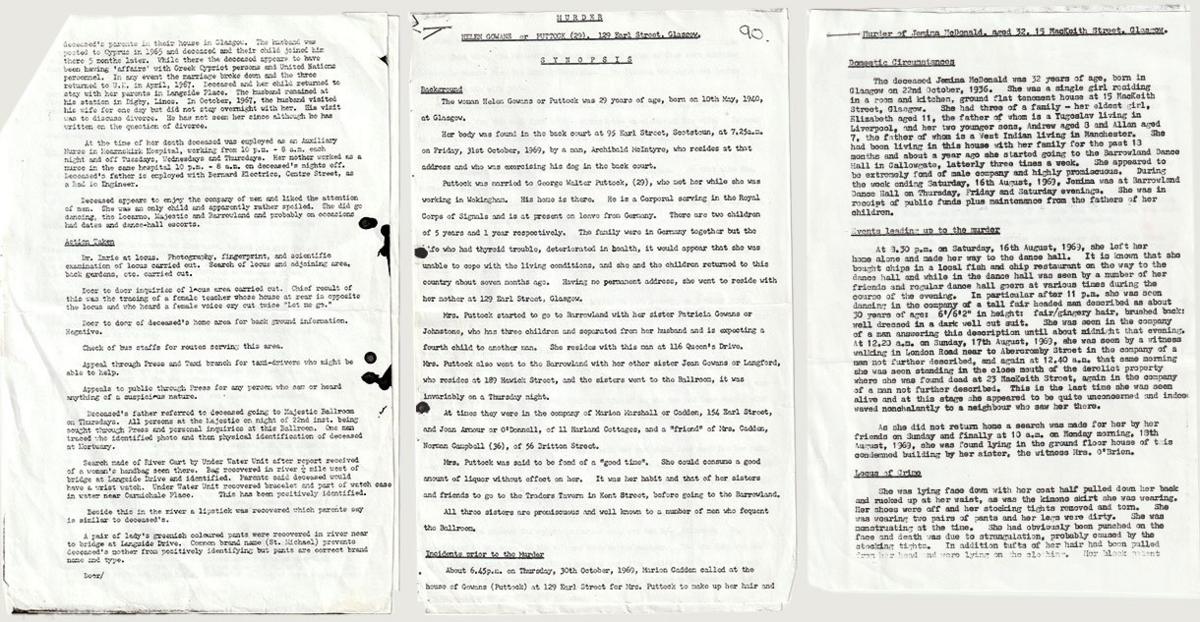

Then, more recently, I dug out the original police case notes that I had held on to - but never published - since I was given them in 1996. The shock I felt was visceral.

Detectives described these women as being "highly promiscuous", "fond of male company", and liking "the attention of men".

It was blatant misogyny. These victims of murder were being judged - and seemingly blamed - for what happened to them, because they had gone out dancing, maybe liked a drink, and possibly liked to flirt with men.

So I decided to return to the case and tell Patricia, Jemima and Helen's stories properly through a podcast

Patricia Charlotte Wilson Docker, aged 25

Patricia was the daughter of John Wilson, a Royal Air Force electronics engineer, and his wife, Pauline. I had thought she was a working-class Glasgow girl who had always lived in the city. She wasn't.

As a child, she lived in Gloucestershire for a while - and in August 1953 she boarded the P&O troopship Empire Orwell with her mother. They were bound for Singapore, where Flt Lt Wilson was stationed. Latterly the family moved to a large house in Glasgow.

Patricia was 19 when she married Alexander Docker, a senior aircraftman with the RAF. They had a son, Sandy. The family lived together in Cyprus, where Alex's unit was based.

They had a babysitter, Yiannoulla, who called Pat "a really nice lady. She always used to dress up very nice." She described her as the type who would wear "skirts, blouses and a suit".

Yiannoulla recalled beach trips with little Sandy, and how she and Pat loved to watch the TV show Dr Kildare. They both wanted to be nurses, she said.

But the Dockers' marriage was in trouble - after the Cyprus posting, the couple separated.

In April 1967, Pat returned to Glasgow, where she became an auxiliary nurse, working nights and splitting her shifts and care of four-year-old Sandy with her mother.

There were similarities in the language used by police to describe all three women

Once a week, Pat would take a night off from these responsibilities and go dancing.

The police report on her death is written with the same judgmental, misogynistic language that was used to describe all three women.

It says she "appears to enjoy the company of men" and describes her as "an only child and apparently rather spoiled".

There is very little detail of what happened during her last night out, after leaving the flat she shared with her parents and son in the Langside area of the city.

She was wearing a mustard-knitted dress and a duffle coat with a blue fur collar. When her body was discovered lying by the door of a garage in a residential lane, her clothes were nowhere to be seen.

These days her son is known as Alex. His life was upended when his mother was murdered.

He was driven away from Glasgow by his father, who was now stationed at RAF Digby and had a new partner. Alex and I corresponded by email - then he agreed to write an eloquent and emotional essay for the podcast.

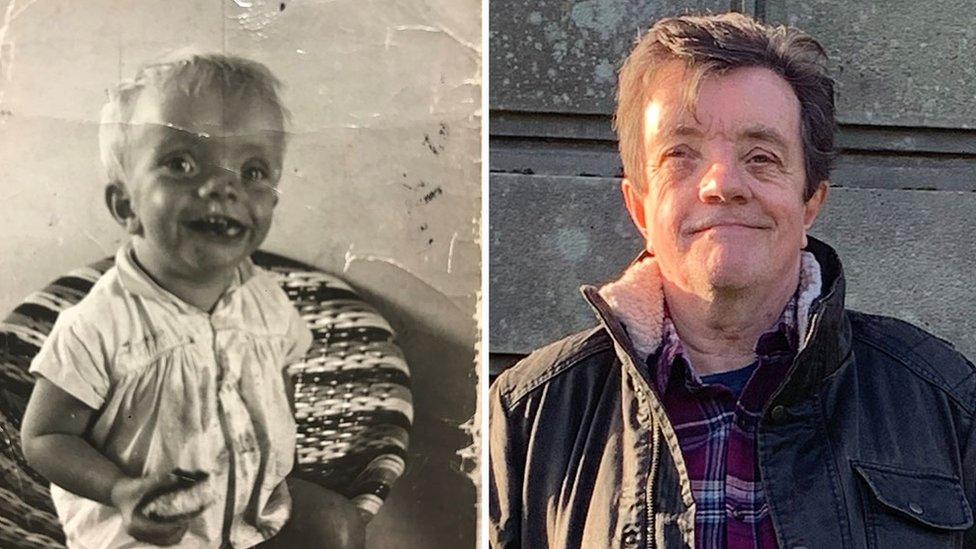

Alex Docker as a child, and as he looks now

He said the flat in Glasgow had been a two-storey tenement above a row of shops.

"I don't remember much of the flat itself, though. I do recall bath time. It was always in the kitchen sink, and I think I must have enjoyed these times because I have a very clear memory of it.

"I can almost picture my mother's laughing face, but the detail is too fuzzy. There is no firm visual imprint.

"I can't see, in my mind's eye, a face - in any situation - nor anyone else's from that time. Their presence is keenly felt, but their physical form [is] indistinct. The few photographs of Pat I have only elicit a weak sense of recognition, if at all."

Alex had never returned to the city of his birth, but as the podcast neared its end, he agreed to meet me in Glasgow. We went to Langside.

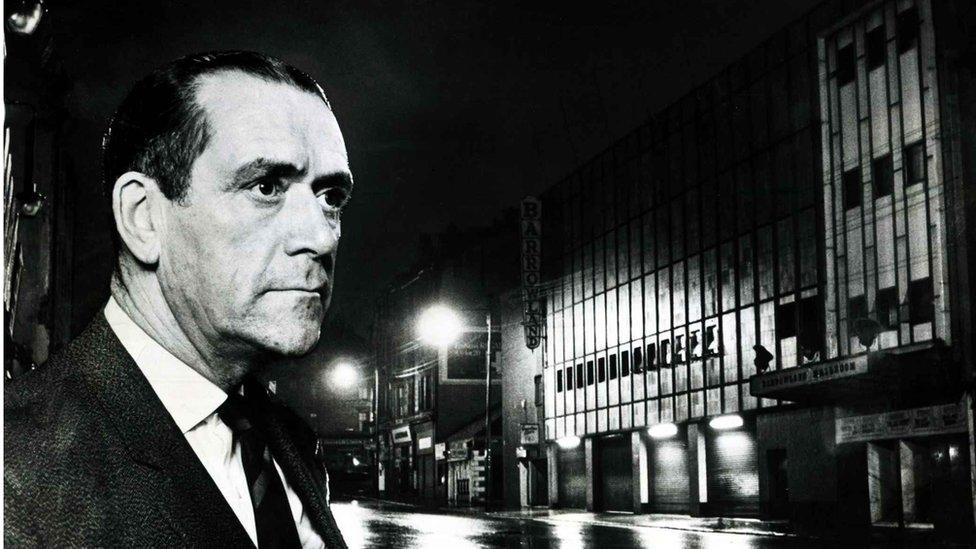

The Barrowland Ballroom was one of the city's popular dance halls in the 1960s

He told me: "In a way this whole thing is like a little box inside my mind that's labelled 'do not open' - and inside that box are two things that really concerned me.

"It's the horror of the death of my mother - my imagination going to places where I wish it wouldn't; the last moments of my mother's life and what her thoughts must have been.

"The knowledge that I was a matter of yards away from where this happened distresses me greatly.

"And the other thing is my grandparents, whose life was hollowed out immediately after this event. They lost their beloved only child suddenly and then, subsequently, me - their grandson - a matter of days later.

"For my part, this podcast has given her back to me in some way. And given me some of my identity back."

Jemima Ramsay Gibson MacDonald, aged 31

A previously unseen photograph of Jemima, with her daughter Elizabeth

Jemima was the woman I knew least about. On the night she died, she had dressed up in a frilly blouse and pinafore dress. She was found by her sister, lying in a derelict building next door to the tenement flat she shared with her three children.

But the story of her life seemed to have disappeared with the tenement building. I knew she loved "the dancing" and came from a big family, but little more.

The police said her eldest child was a girl, Elizabeth, who was then aged 11. Her father was "a Yugoslav" according to the notes. Jemima also had two sons - Andrew, 8, and Allan, 7 - and their father was said to be West Indian. Police notes say: "Jemima appeared to be clean in her person and her home, and children were well cared for."

I wanted to know what happened to those children. It emerged that when Jemima was killed, child welfare officials took Elizabeth to one residential care home and her brothers were taken to another. One minute they were living with their mum, just across from their aunt, and the next they were torn apart.

I spent months trying to find them, worrying that the care system would have chewed them up. I ordered birth certificates and built family trees and eventually discovered that the two boys had changed their surnames - as had their father.

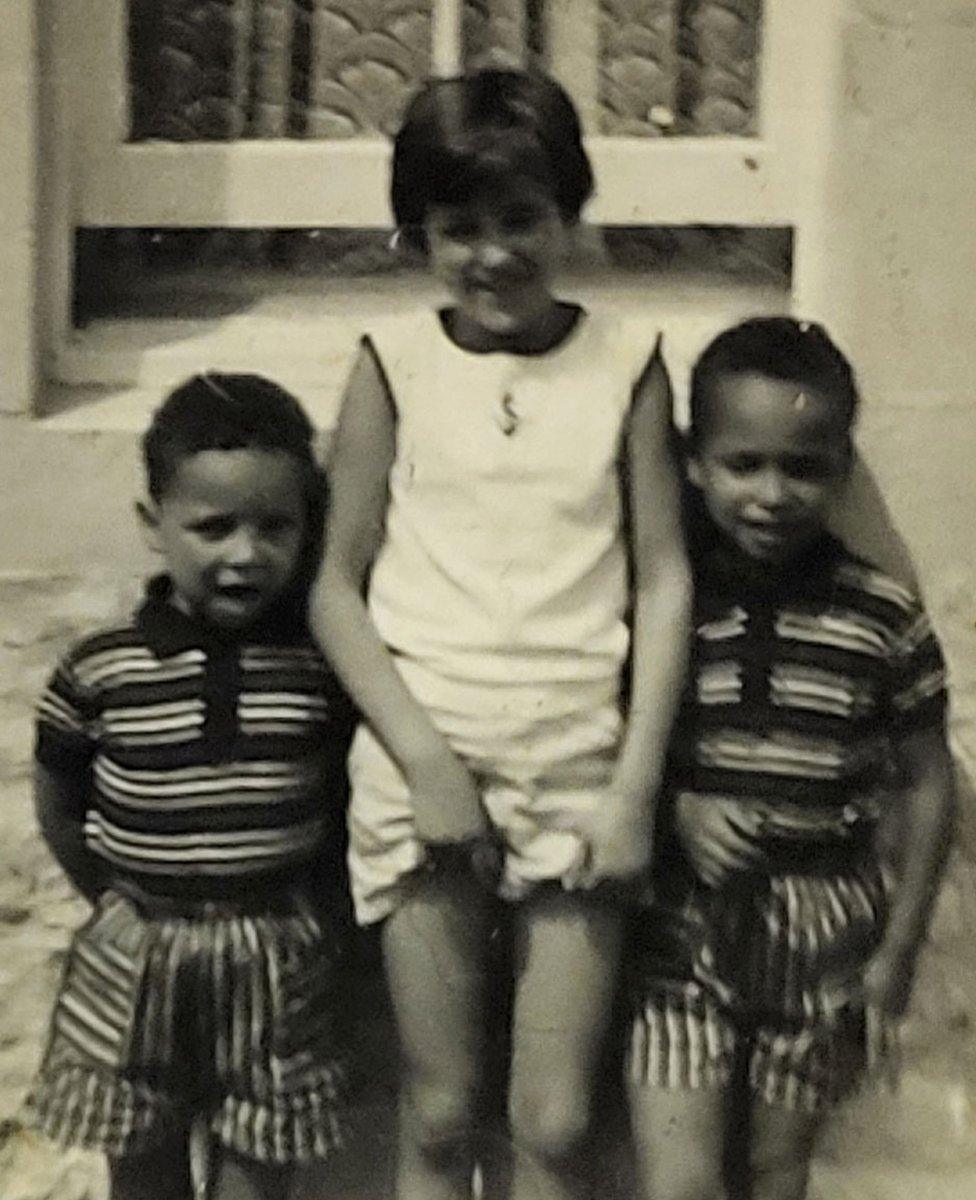

The children were split up after Jemima's murder

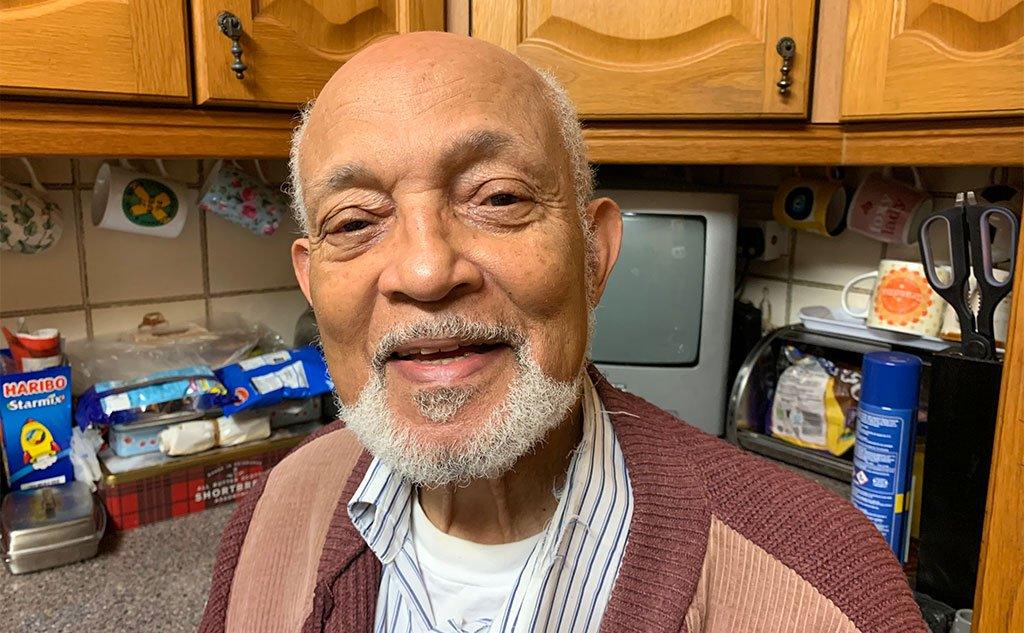

I was stunned to find that Eldridge "Bunny" Mottley was alive, and living on the outskirts of Manchester.

He knew Jemima as Mima, and while they had separated when their boys were very young. He still spoke fondly of her.

"I can see her walking up the road - and she never used to walk, she always used to be skipping and jumping," he said.

"She wasn't backward at coming forward... we instantly hit it off. It was as simple as that. She was always absolutely immaculate.

"She gave me two lovely sons, and they have been a credit to me and to her."

Eldridge "Bunny" Mottley

One of those sons, Allan, recalled the time that his mother had got her three children out of bed to watch the moon landings.

He came to see me in Glasgow, with his wife Norma and daughter Sammy, and together we visited Jemima's grave.

He said: "Nothing was ever explained to us. Well, not to me, anyway. [That's] probably why you don't think about it. I just get on with my life.

"So, you know, it's something that happened. Mum died. Next minute we were living with my dad."

I showed Allan what the police had written about Jemima.

Their notes said she "appeared to be extremely fond of male company". The report said she had been at the Barrowland Dance Hall three nights in a row in the week before her murder, and was "in receipt of public funds, plus maintenance from the fathers of her children".

Allan Mottley, at his mother's grave

Allan was quietly indignant.

"It's as if she shouldn't have been allowed to have a life because she was single and she had children," he said.

Allan stressed that his mother had not just disappeared and left her children alone.

"We were looked after, because we had family next door. I suppose, like any single parent, with three tearaway kids around your ankles all day, you've got to have a release.

"If family were willing to look after them while she went out, there's nothing wrong with that at all."

Helen Gowans Puttock, aged 29

Helen was at the Barrowland with her big sister Jean on the night that led to her murder. With a crucial, surviving witness, her story had always had the most detail - yet there was still so little known about her.

In 1996, I interviewed Jean. She told me her sister was always called Ellen and that she was "a good-looking lassie. She loved it up the dancing."

The day they went to the Barrowland, Helen had gone to C&A and bought a black dress with gold buttons up the front. Jean said her sister was tall, well-dressed, that her new dress was lovely. She wore it the night she died, along with fake-fur ocelot-print coat.

Helen had worked on the buses and been a furrier and a bookie. When a romance broke up, she went down to stay with her brother in Reading. That was where she met her husband, George Puttock, a lance corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals. The two 23-year-olds married in March 1964.

The couple had two children, David and Michael - and when George was sent to Germany, his family followed on. But Helen didn't like it there and returned to live with her mother in Earl Street, Glasgow, in mid-March 1969.

Helen Puttock, with her husband George (right) and a friend

I discovered that the Puttock marriage was in trouble and Helen had told George it was over. He travelled to the city on his next leave from the army, on 17 October, in the hope that he might win back his wife's affection - but Helen said she didn't love him anymore.

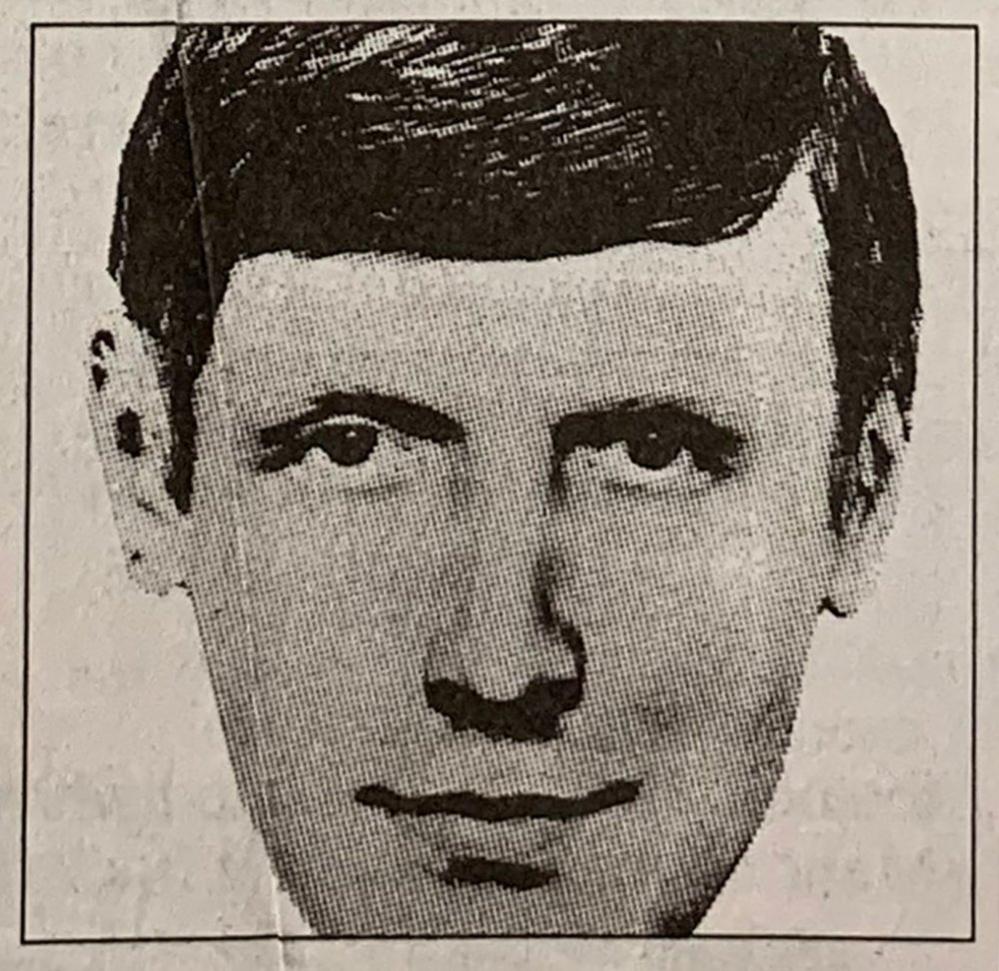

Jean was in the taxi with Helen and the man she left the Barrowland with on the night of her murder. This is the man police believed killed her.

Jean remembered he quoted small bits from the Bible and claimed his name was John. These details were collated by the media - and so 'Bible John' was created.

But Jean felt this was a distraction: "If we hadn't been talking about religion and football that wouldn't have come up," she said.

I found Helen's cousin, Margaret Work, and her daughter, Elaine Paterson, who told me that the family was left broken after Helen died.

"It ruined a whole family really," said Elaine.

"George took the kids away, down to England. So old Jeannie [Helen's mother] not only lost her daughter, she lost her grandkids. And Jean lost a sister."

Jean told me the same: "My mother never ever got over it."

Helen's body had been left in a back yard, just eight doors away from her mother's top-floor flat.

Det Supt Joe Beattie led the murder investigation

The Bible John investigation became one of the largest ever carried out by Scottish police.

More than 5,000 people were interviewed - and the inquiry saw the first use of a police photofit of the suspect.

But no arrests were made. One suspect's body was exhumed after the case was reopened in 1995 - but he was eliminated after tests failed to find a DNA link to the killings.

It is now more than five decades since Patricia, Jemima and Helen were killed.

The murders left suffering in their wake. But through their families, we have now learned so much more about these three women who loved to go dancing.

They are no longer just a footnote in the Bible John story.

Bible John: Creation of a Serial Killer Audrey Gillan explores the lives of the three women killed in Glasgow in the late 1960s

Related topics

- Published24 November 2022