Fans get rare chance to see lost Billy Connolly Big Banana Feet film

- Published

See how Sir Billy's big banana feet became part of his iconic early routines

Billy Connolly has appeared in hundreds of films, documentaries and shows over the years.

But Big Banana Feet is a rarity. A raw, edgy fly-on-the-wall documentary which follows the comedian, on the cusp of fame, around a volatile landscape.

The film was made in 1975 at the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Just a week before his appearance, three musicians from a popular cabaret band were shot and killed by a paramilitary group while touring Ireland.

Camera man David Peat recalled in a documentary that 30 weapons were confiscated from the audience arriving for Connolly's show.

The film's cameraman recalled weapons being confiscated ahead of one of the Big Yin's shows in Northern Ireland

The challenges of making the film were just the start. It had a limited release in cinemas in the UK, followed by a small video release, then the distributor went bust and the film went missing.

Only one copy remained, in the Pacific Film Archive where director Murray Grigor left it in the 1970s, as he was unable to fit the three reels into his transatlantic luggage.

A video copy of that version was shown at the Glasgow Film Festival in 2012 but with no public copy, it has never been seen since.

Billy Connolly arriving in Northern Ireland for his 1975 tour

But the tenacity of film archivist Douglas Weir, who works at the British Film Institute (BFI), has secured the film's future.

Born in Govan in 1982, he is responsible for restoring other Scottish classics like Gregory's Girl and That Sinking Feeling and has been searching for a copy of Big Banana Feet for the past decade.

He said: "I've always had an eye out for Big Banana Feet. It's not uncommon for films to be lost or scattered after a distributor or a lab goes bust.

"They can turn up at car boot sales or in people's attics or on eBay. I got an alert one evening to say there was a 16mm film for sale.

"They'd spelled Billy Connolly incorrectly and they'd misspelled banana so no one bid on it, and I got it for £50."

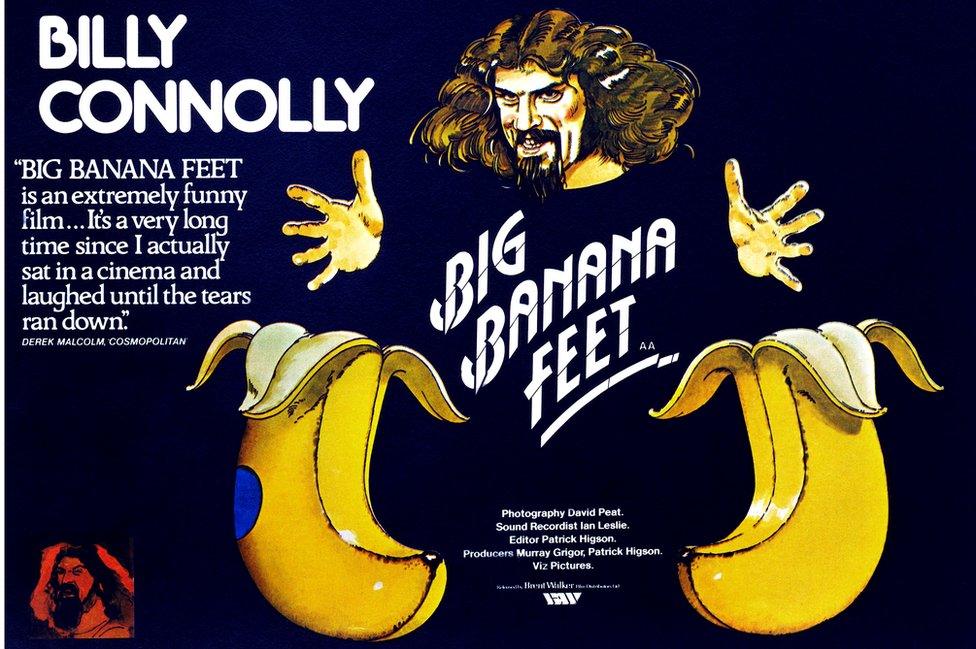

The original film poster for Big Banana Feet

Douglas produces one of the three canisters from under his desk at the BFI and takes a long sniff.

"You can tell a lot from the smell of film," he says.

"If it smells of vinegar, it's a problem.

"If it's pre 1950s and smells of old socks, get it out of the building because it's highly flammable."

In the film, Billy Connolly flies to Northern Ireland to perform at the height of the Troubles.

Labels on the case suggested the film has had quite a journey, including a showing in a village hall in the Falkland Islands.

But for the past few years, it has been undergoing restoration.

As well as improving colour and audio, dust specks and scratches have been removed. Two jokes, censored in the cinema release have been added back in.

But Douglas says he wanted to improve the look of the film, without compromising the original.

Douglas Weir tried to keep the grainy look of the film while cleaning it up visually for a 2024 audience

"It's a 16mm film, shot on a hand held camera, in what light is available. It's in dingy dressing rooms, and hotels, bars and pubs so it looks grainy and I didn't want to lose that.

"For most of the show, Billy Connolly is wearing a black leotard and against a dark curtain so the trick is to bring out as much detail as possible without losing the atmosphere."

The banana boots are now on permanent display in the People's Palace in Glasgow. Image: Glasgow Life Museums

The one burst of colour is in the iconic banana boots of the title. Commissioned for the tour, they now reside in a museum in Connolly's home city of Glasgow.

"They made one and I tried it on, thought it was amazing," he says in the film.

"And I said carry on with the other one. And they phoned up to say it was ready and said I must warn you, they're not identical. But then, bananas never are."

Much of the comedy in the film is improvised, onstage and off, and the joy is watching Connolly early in his stand-up career.

In one scene, a member of the audience throws him a rose, which he pretends is a bomb. He says afterwards that he realised in that moment that he'd won them over.

Connolly and his wife Pamela Stephenson have given the project their approval. They say they're delighted the film has been given a new lease of life.

Big Banana Feet gives an insight into Connolly as a performer at the start of his career

The restored version will be shown at the Glasgow Film Festival on 3 March and the BFI plans to release a DVD later this year.

Douglas will be at the festival to talk about his role in preserving the film, alongside director Murray Grigor.

"I'd like to make sure there's a copy in the Scottish Film archive as well as at the BFI, so it can never go missing again," he says.

"I am so lucky in my job to be able to find films and restore them so they'll be available to everyone for years to come.

"It's like Raiders of the Lost Ark, to be able to put the treasure safely back on the shelf at the end."