Could Glen Rosa be the Clyde's last traditional ship launch?

- Published

Glen Rosa is the heaviest ever ship to be launched at Ferguson shipyard

MV Glen Rosa will slide down a slipway into the Clyde on Tuesday. It is the second of the two CalMac ferries being built at Ferguson's shipyard in Port Glasgow whose construction have been beset by problems and delays.

Will we ever see such a large ship launched this way again on a river that once dominated world shipbuilding?

The ritual of a bottle being smashed into the hull before a great ship glides into the water is an iconic - but increasingly rare - scene in shipyards.

Thousands of Clydebuilt ships, among them great names like the Queen Mary, the QE2 and the battlecruiser Hood, have been launched this way.

But for many shipyards, the "dynamic" launch method, as it's known, has fallen out of favour.

Sending thousands of tonnes of steel and aluminium down a slipway under the forces of gravity always carries an element of risk.

Doing it safely requires meticulous planning as well as skills and experience possessed by a dwindling number of experts.

Watch: A century of iconic ship launches on the River Clyde

On the day Glen Rosa enters the water, 66-year-old shipwright Andrew Cochrane will retire after a shipbuilding career spanning 51 years.

He's lost count of the launches he's witnessed but he reckons it's just under 100. For Andrew, nothing beats a traditional slipway launch.

"This is the only yard left on the Clyde that believes in the dynamic launches - the traditional way, the best way," he says.

"I'm always proud - and I'll be proud of this one because it's my last one.

"It's the camaraderie amongst the boys - the pride once you see the ship leaving the slipway and going into the water."

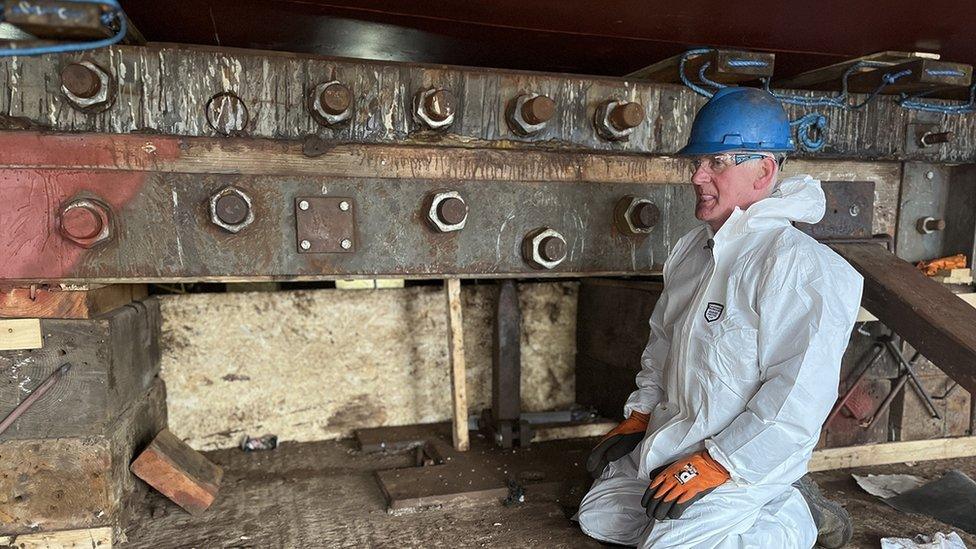

Shipwright Andrew Cochrane is one of those responsible for launching Glen Rosa

Touching his heart, he says: "You get a wee bit in there. It's all pride."

But could this be the last dynamic launch on the Clyde?

Ferguson's currently has no new ship orders. The yard is still waiting to learn if it gets the contract for a fleet of smaller CalMac vessels, similar to ones it has built on time and on budget in the past.

"I'm hoping everything goes well for this yard and they get work," says Andrew.

"This yard can prove itself once again because they're a great bunch of workers in here."

The ship rests on the sliding ways, which will travel with it down the greased standing ways into the water

The traditional method of ship launching hasn't changed since Andrew started work at the long-gone Scotts shipyard in nearby Greenock at the age of 15.

As the ship is assembled on the berth, long wooden tracks called launch ways are constructed on either side of the keel.

They are in two parts - the standing ways, which will guide the ship into the water; and the sliding ways, a long wooden cradle which is fitted directly on top and travels with the ship as it descends into the water.

The surfaces are all heavily greased. The shipwrights have got through 15 barrels of grease and 10 barrels of tallow in preparation for the launch of Glen Rosa.

During World War Two, when grease was in short supply, a ship in Texas was once famously launched using 3.2 tonnes of bananas.

Restraining shores and stoppers are removed just hours before the launch

The vessel also rests on heavy timbers called shores, and there are wedges to keep it in place.

As launch day approaches, the shores and wedges are removed from the bottom and the side until the ship rests entirely on the launch ways.

Hours before the ceremony, stopper blocks and the restraining shores - angled timbers wedged between metal brackets on the hull and concrete berth - are also taken away

"They're the very last bits of timber holding the ship," explains Andrew.

"The only way to remove these shores is to cut them off - a metal bracket is cut off with burning gear."

All that prevents the ship moving now are a pair of daggers - strong steel levers, hinged at one end, which serve as a trigger mechanism.

They are held in place by vertical metal pins which are winched away by the shipwrights the moment they hear the bottle smash.

The daggers are held in place by a metal pole that is pulled away when the bottle smashes into the hull

The winch pulls the pins away, the dagger drops and the sliding way then slides into the water.

For retired naval architect Craig Osborne, who has advised on Glen Rosa's launch, a lot of maths and physics is also involved, calculating forces and centres of gravity.

The vessel weighs just under 3,000 tonnes.

Craig says that for a few seconds, about 30% of the weight of the ship is taken on a metal structure called the fore poppet.

"You have to ensure the wooden supports for the launch ways can take that weight - but it's over in the flash of an eye," he explains.

Often a ship won't slide off immediately. Glen Rosa's sister ship Glen Sannox - which was much lighter - remained stubbornly static for almost 90 seconds while hydraulic jacks were used to coax it along.

A metal structure called the fore poppet protects the front of the ship from a surge in load as the stern enters the water.

About 20 seconds after the ship moves, it's all over as the vessel floats for the first time.

The waiting tugs quickly "catch" the drifting vessel, ready to shepherd it to the safety of the quayside where months of "fitting out" work lie ahead.

There's a lot that can go wrong.

"Stuck on ways" is a frequent entry in the records of Clyde ship launches as a ship failed to make it all the way to the river.

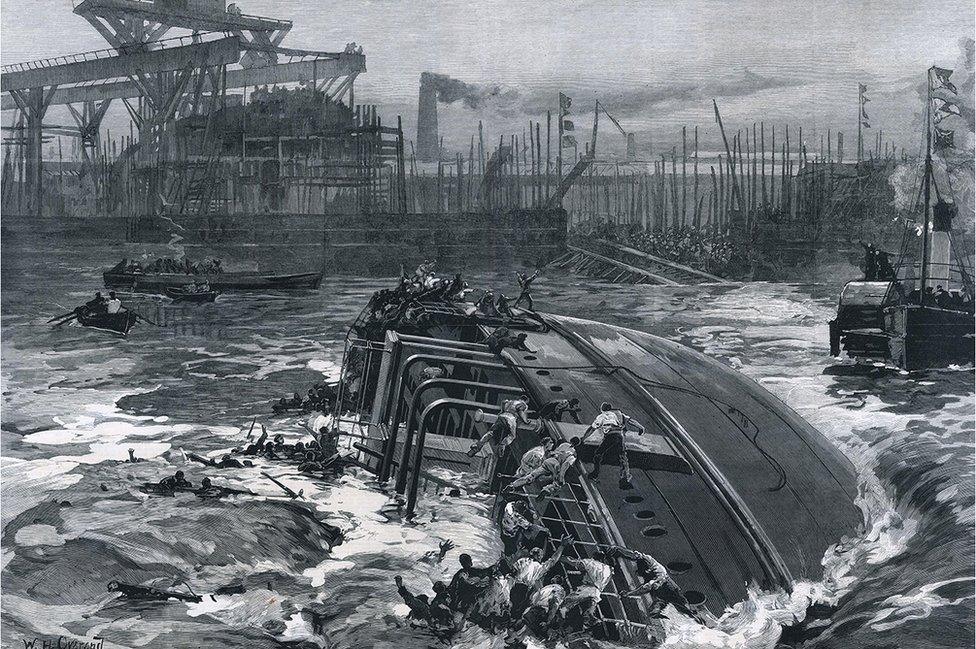

The most disastrous launch came in 1883 when the steamer SS Daphne sank minutes after leaving the slipway at Alexander Stephen and Sons in Govan with 200 workers on board.

Anchors had been attached on either side to slow the ship's movement as it entered the water, but one of them dragged along the river bed.

Caught in the current, the ship capsized in deep water, claiming the lives of 124 men and teenage boys.

In 1883 more than 120 workers lost their lives when a ship launch in Govan went disastrously wrong

The rigorous safety standards of modern-day shipbuilding means there's little chance such a tragedy will be repeated, but for those planning the launch it remains a nail-biting time.

Twenty miles up river in Govan, the only other Clyde shipbuilder BAE Systems abandoned slipway launches more than a decade ago.

Royal Navy warships are now built on a level surface, then manoeuvred using self-propelled trailers onto a giant semi-submersible barge which carries them to deep water and lowers them down gently.

HMS Glasgow was loaded onto a semi-submersible barge and gently lowered into the water in Loch Long

James Bowie - engineering director at Malin Abrams, which co-owns the barge with Augustea - believes the technique has several advantages.

"It saves money because you can reach a more advanced stage of completion before the launch - and it's safer," he says.

Elsewhere in the world it is common to build ships in dry docks which are then flooded, allowing the vessel to be "floated out".

The last ship to be launched at Ferguson's prior to Glen Rosa - a flat-bottomed fish farm workboat named Kallista Helen - was rolled out on giant airbags.

Kallista Helen was launched at Ferguson's three years ago using airbags

Launch ceremonies have their own traditions and rituals. A bottle of champagne is commonly smashed against the hull for the spectacular spray it produces, although in Scotland whisky is sometimes the preferred christening liquid.

Vessels built in Scotland but destined for India have sometimes been christened with coconut milk.

The guest invited to "sponsor" the vessel is usually a woman - who then becomes the ship's "godmother".

At Ferguson's a small hammer is brought down onto a blade, cutting a cord that releases a trebuchet-like device - which then propels the bottle into the ship's bow.

In 2005, at the launch of the fisheries protection vessel Jura, the bottle failed to smash so a shipwright had to finish it off with a large hammer. The glass is usually scored to weaken it.

In the past the shards and ribbons were then gathered up and presented to the "lady sponsor" in a wooden casket, and a "flower girl" presented her with a bouquet.

A specially bottled whisky will be used to christen Glen Rosa

Glen Rosa's launch will be a little different. The ship will have no sponsor but will be named by Beth Atkinson, a newly-qualified welder who has just completed her four-year apprenticeship.

She'll be joined on the podium by four other female apprentices, who are among more than 100 young people trained in traditional shipbuilding skills at the yard over the past decade.

Glen Rosa will be the 363rd ship built at Ferguson's during its 121-year history and it will be the heaviest. If it doesn't leave the slipway this week it will be December before the tide is next high enough to launch during daylight hours.

A fact often overlooked in Scotland's ongoing ferries saga is that half of CalMac's large vessels are Ferguson-built ships, many of them soldiering on well beyond their expected service life.

Glen Sannox and Glen Rosa - the first ships built in the UK with a liquefied natural gas (LNG) propulsion system - have been blighted by design problems and a demanding specification.

Eight years after the first steel was cut, and six years after they were due to be delivered, the ferries are still unfinished and nearly four times over budget.

The yard's 316 workers have often been left embarrassed and demoralised by events beyond their control.

But for onlookers who gather in Port Glasgow on Tuesday it will be a day to set those controversies aside and celebrate hard work carried out in difficult circumstances at the last surviving shipyard on the lower Clyde.

A ship launch is a big day for the local community - one which has lost nearly 1,200 jobs in the past 18 months at companies like Amazon, EE and IBM. The skilled work and traditions of Ferguson's shipyard are still valued in Inverclyde.

If the yard navigates its way through the current choppy waters, there may be more dynamic launches in future - but probably involving smaller vessels.

The launch of Glen Rosa could well be the final time a ship of this size is launched down a slipway into the Clyde.

All images are copyrighted

Related topics

- Published26 November 2023

- Published6 June 2023